BACCALAUREATE SERMON, PREACHED BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE COLLEGE SUNDAY, JUNE 24, 1906

TEXT:—"Wisdom is the principal thing,therefore get wisdom: yea with all thy gettingget understanding," (or wisdom). Proverbs 4:7.

There is to my mind a certain inherent ugliness in the word "get," and it is not above reproach in some of its associations, but we shall all agree that it is one of the most characteristic words of our language. It pervades our common speech with the force of a race word. All the initiative, the acquisitiveness, the pride of possession which mark the Anglo-Saxon find ex. pression in this homely syllable. It is not to be wondered at that our translators have given it a frequent place in the transfer of . thought from the terse and sinewy Hebrew."

I have called your attention to this word because it gives so much strength and movement to my text. This old- time writer is speaking about wisdom, but not in any abstract or academic way. He speaks of it just as if it were something to be found in the market place or in the field. I shall try to speak to you in this same spirit concerning wisdom. My subject is the present call to wisdom, the call to youout of your generation. I shall try to show you that at this time—under present conditions of privateand public life— "the principal thing is wisdom," and in attemptingto do this I hope to be able to say to each one of you, through every sentence which I may utter, "therefore get wisdom; yea with all thy getting get understanding."

Of course this insistence upon the geting of wisdom means that wisdom can be acquired. Doubtless some men are born with a greater capacity or aptitude for it than others, but wisdom is not an endowment. Neither is it entirely a matter of experience. It is chiefly an acquisition, something to be gained in greater or less degree by all men as they give the rightful place to it among the powers which ought to belong to them in their maturity. Some men are foolish because they do not care to be wise. Some men lack wisdom because they do not take time to be wise. Some men fail to be nobly wise through cowardice, the constant and most serious foe of wisdom. But all the while wisdom is something to be had through desire, through patient seeking, through courageous action.

All this will become plain to you if I can rightly interpret the present call to wisdom, the call of your generation. The cry of the past generation, especially of the past decade, has been for efficiency. We have asked everywhere and unceasingly for the efficient man, meaning thereby the man of results. We have striven in all possible ways to produce him. School and shop and street have been in close competition toward this end. We have gained our end. We have produced the efficient man, the man capable of results, able to show his power not in one way but in many ways. The most conspicuous type, the man of vast fortune, exists because other men of efficiency are at work with him, and for him, and unto him. But now that we have the efficient man and the results due to him, we are not quite easy or safe in his presence, nor are-we as sure of the results which he has given us!as we would like to be. And yet we do not want to lower our standard of efficiency, we do not wish to produce a feebler or less effective man. We do not care to change the proportions of life with which we have become familiar, and return to a world of scant equipment and of hesitant forces. It would be the merest cant on our part to pray for adversity in place of the growing resources and the enlarging opportunities of our time. What we really want is security, confidence, satisfaction concerning the things we have, satisfaction also in our way of getting them, and a more satisfying sense than we now have that we are really getting the best things. I think that we are beginning to be willing to pay the price of these assurances. At any rate we have come to the stage of reflection, and are unwilling to trust ourselves any longer to the arbitrary and unregulated power of the merely efficient man. Hence the unmistakable call to wisdom where once we heard nothing but the cry for efficiency.

As the call is new, this call to you out of your generation, let me try to interpret it to you in some of its deeper meanings. Ido not believe that it is the call of mere caution or fear. Ido not recognize in 'it the voice of a traditional conservatism which is always in protest at the rate of progress. Ido not detect in it the accents of a worldly wisdom, which is indifferent to principles, afraid only of consequences. It seems to me to be at its best a brave, honest, believing call, a veritable call of the spirit in men to the spirit in men: otherwise I would not repeat it in your presence or try to interpret it to your understanding.

Let me say then in the first place that it seems to me to be one of the many and oft repeated calls to righteousness, taking now the form of an appeal to the mind, especially to the trained mind, to the end of its own freedom. There have been ages in which the greatest danger to righteousness lay in passion, sometimes in wild and ungovernable passion, sometimes in morbid and degenerate passion. There have been ages in which the greatest danger to righteousness lay in bigotry, in the narrowing and hardening of conscience in the assumed interest of truth. The chief danger to righteousness in our time lies in the perversion of the intellect. Too many men amongst us are selling their minds in the market place. Wrong schemes prosper in many cases because they are devised or carried out by men of brains in the employ of men of will. In some instances subordinates are guilty of practices which their principals would not commend. The desire, for example, of a manager to make a good showing in the business must be under the control of both honesty and justice, else there will be harm done to those below him, or injury to the business itself. I put you on your guard against the bartering of the mind for any supposable returns in position or in money. The real return, the actual reward inevery such case, is servitude.

In saying this I do not dissuade you from putting your talents at the service of men of accumulated power, or at the service of corporations. The presumption is in favor of integrity in the business world. If you enter this world you have the right to that presumption. But in any particular case, if you find that you have been deceived, the sooner you part company with a dishonest or unjust man, or with a dishonest or unjust corporation, the better for you. you cannot afford the inevitable result of such service—servitude. On the other hand identification with a man or house, or corporation, of honorable record, clean and humane methods, and of satisfying enterprise ought to call out your unfailing loyalty and your unstinted effort. You can afford to put into such service whatever mental power you have in the assurance of the appreciation of the highest result of your power, namely, mental rectitude.

The present call to wisdom is nothing less than a challenge to the mind of your generation to preserve its moral freedom. Can you think of a nobler call? Is it not as noble a thing to keep the mind free from the slavery of dishonesty, as it is to keep it free from the slavery of superstition or bigotry? Yet we applaud the men and the ages which fought for this kind of freedom and passed on their victory. Do not ignore or deny the challenge of your age to mental freedom, through mental rectitude, in the presence of the enslaving power of corrupt wealth. Make it easier, not more difficult, for your sons and for all men who may come after you "to do justly, to love mercy," yes and "to walk humbly with God," not meanly and cringingly with men, but humbly with God.

This new call to wisdom is then, to begin with, a call to self-respecting independence. It strikes at once the note of freedom. It strikes perhaps a deeper note as it recalls the mind of your generation to its obligation to truth. If the first note is freedom the second is loyalty. We have fallen upon a singular and in some cases glaring inconsistency in the material development of our time. This material development is based upon scientific truth, the first condition of which is mental honesty. The whole process of scientific training, with all the results consequent upon it, has involved from first to last this quality. It has been a costly training, costly in the amount and character of the instruction required, costly in its equipment, costly through the insistence which it.has placed upon the trustworthiness of the results demanded. This training toward scientific truth has been costly also in some of its incidental effects. Wherever it has been adopted and applied outside the natural or physical sciences, as in the realm of history, or philosophy, or theology, it has changed opinions of men and of events, it has revolutionized theories, it has modified religious beliefs. It has cost many men very much to accept these changes in inherited opinions, in established and working theories, and in personal belief, but they have accepted them loyally and unflinchingly in the interest of truth. The critical habit of the age, which has wrought such changes elsewhere in the interest of truth, has paused and grown hesitant and ineffective and cowardly before the material development which it has done so much to set in motion. The methods of building up and expanding great business enterprises have not been subjected to the same tests which have been applied unsparingly by critics, and bravely accepted by all who have been concerned with scientific investigation, with historical research, or with religious beliefs. The inconsistency is, as I have said, singular and glaring. At the very point where the scientifically trained mind might have been expected to assert its morality, just where it has had to do with material values affecting human life, it has failed. It has tolerated shams, it has jockeyed with values, it has devised and executed frauds: and in so far as it has done, or allowed the doing of any of these things, it has been disloyal to its own training. It is inconsistent to create a value through all the scrupulously exact processes of its creation, and then to give it commercial license. We must learn to handle material values with the same care which we exercise in creating them. We cannot afford to have one standard of honesty in the creation of wealth, and another standard in the manipulation of wealth. The inconsistency is grievous. The present call to wisdom is therefore in part a recall of the trained mind of your generation to a constant and continuous obligation to truth. There is no point at which it can discharge its obligations, and remain a factor in the productive power of the world. So long as it concerns itself primarily with material values, it must guarantee them to the public. This is a fair demand. Speaking in behalf of those whose business it is to train the mind to efficiency, I accept, in all which it implies, this demand that it be trained to morality.

I give you one further thought in the interpretation of the present call to wisdom. First, as we have seen, this call is a challenge to the trained mind to a self-respecting independence: then it is the summons to the mind to a consistent morality: and now at last it makes its appeal to the mind for unselfish forethought. There is no form of the call to wisdom which is more serious than the protest which it utters against the selfishness of living in and for the present. It is the protest which above all protests we need to hear. We belong to an age which lives in and for itself. The spirit of the age is infectious. All things are saying to us, every man is saying to his neighbor, "live in the now, live to the full.'' The world is just now so rich and splendid, so full of desirable things, that it does not seem as if it could always, or for long time, be held in possession. Men recall the poor and scanty and struggling periods which have had their place in the history of every people. Many a man recalls a yet nearer time in his own experience of want, and hardship, and unrewarding toil. The contrast with the abundant rewards and relieving methods which are now his, enhances the value of every day in the life of the present. And who knows what is to come ? Who can date the return of the hard economies, the severe virtues, the struggle for existence? Who can declare even the law of diminishing returns? Who can forecast the economic changes, the social reversals, the limitations upon national supremacy, which may give us the environment of another kind of world? Somen question within themselves : and so they reason toward the practical conclusion—"Let us seize the present: let us live in the day."

No observant or sensitive man can fail to see or to feel this intense eagerness to live in the present. It explains in part the quickening of the pace in education.. Education is becoming more and more a means to some immediate end. The end is so near, so tangible, so tempting, why stop on the way for the enrichment of the mind or the enlargement of desires. The scholar of our time is as quickly professionalized as any other man who looks forward to a profession. The scholar who is to become a teacher, even on the higher grades, is quite as much in haste, and often more ready to abridge his training, than his fellow student preparing for the law, for medicine, or for the ministry.

The same eagerness to live in and for the present is more manifest still in its effect upon social life, especially upon the life of the home. The children of the rich are put out earlier and earlier because the home can no longer make suitable provision for them, and keep up the social round of exciting and exhausting pleasures. The home of the old New England families is no longer charged with the spirit of sacrifice which once characterized it. Children are not so much as formerly an investment. Something of the money which once sent boys to college goes into the cheap luxuries of the house. I make no sweeping statement at this point, but the difference between the former and the later times is brought out by the social sacrifices of the newer peoples who are beginning. to appropriate the old New England custom of making the children of the home the great investment, the mark of their unsel fish fore-thought.

I do not dwell upon the innumerable signs of this eagerness to live in and for the present in the business world. We expect to find much of it there. There is more immaturity in the business world than anywhere else, and on the whole I think that it lasts longer with the individual man. As a very sagacious observer recently said, the proportion of failures, absolute failures, is nowhere else so great. Failures, however, are not to be deplored so much as successes which prejudice the future, as when markets which have been fairly won are lost by cheapening the product: successes which are gained at the expense of the public through corrupt or fraudulent practices: and successes, most despicable of all, which destroy life, which make "the poverty of the poor their destruction. ' There is no complaint of our time so just as the complaint against indifferent wealth.

The call then to wisdom among men, whoever they may be, who are living too much in and for the present, is a straight appeal to their unselfishness; and the unselfishness of the mind is best expressed in forethought. It says to the man who really proposes to give himself to others, who aspires to one of the self-denying callings, but who is in haste to be about his business,"See to it that in giving yourself you make a sufficient gift. Enlarge yourself, enrich yourself, refine your power. Be not content with the spirit of giving. Have much to give."

It says to the home, "Give freely of self, not over much of money to your children. Anticipate the needs of men which may be met and satisfied through them. Train them for service, equip them for it, yes, consecrate them to it, if need be, by your sacrifice."

It says to the street, "Be honest that the nation may live, that the social order may be preserved, that the good name of the people may be exalted among the peoples of the earth. Make your gift to the future as much as you will in money, but more in honor. "

; Now in this call to wisdom out of your own generation, as I have interpreted it to you, is there anything irrational,. cowardly, or merely prudential? Is it not, as I said at the beginning, a brave, honest, believing call, the call of the spirit in men to the spirit which is in you ? I do not say that it is a recall from efficiency to morality. I say rather that it is a call to morality without which there can be no more efficiency. Unless we can make the efficient man moral, he has already become useless.

I have been speaking of the present call to wisdom as a special call to the trained mind of your generation. It has to do with all men everywhere, but it is most insistent and urgent wherever it can get a hearing among men of trained power. To you and to men like you all over the land it is saying, "Do not sell your minds. Self-respecting independence is above price. A man is of no value to himself who is not free."

"Be consistent in the use of mental power. Never discharge your minds of their obligation to the truth. At whatever stage you deal with values deal honestly."

"Do not live in the selfish employment of the present. Think, plan, work, sacrifice for the future. Be sure that something about you that you have said, or done, or suffered goes over into the service and remembrance of men."

Thus interpreted is not the ancient word true today; so true that no man can deny its premise, nor evade its conclusion? "Wisdom is the principal thing, therefore get wisdom; yea with all thy getting get (wisdom)."

MEN OF 1906: At no time within my official connection with the College has a class gone out into a clearer moral atmosphere than that into which you now go forth. It is possible for every one of you to read moral principles in the light of effects and results. You can measure the outcome of personal force whether expended honorably and unselfishly or in dishonor and greed. You can see precisely where definite courses of action, good or bad, have led and are leading individual men. You can estimate moral values in the terms of public opinion, in the opinion even of the average man.

But I would not have you rely upon the present moral illumination for your moral safety or for your moral efficiency. Public sentiment is fitful. Today aroused, stimulating and restraining or directive; tomorrow dull, confused, depressing. A noble career never starts out of other men's opinions or convictions. The inciting and sustaining power is always in the man himself. His vision is his own. His convictions are his own. He makes his own path of moral progress. He creates when he cannot utilize opportunities.

I bespeak for every one of you a well defined, consistent, and satisfying career. You may do many things. You cannot afford to do them on different moral grades, or by different moral methods. The most wasteful business in which any man can engage, wasteful of reputation, of power, of personality, is the business of experimenting with the world morally. If the thing you want does not come to you at once except through moral surrender, simply wait your time. Learn to postpone success. When it comes, let me say, it is yours by every right of justice, of honor and of humanity.

So I bid you go forth "without fear and without reproach." It is a great thing for a man to have his chance in this world. You have your chance. Rejoice in it. Honor it. Be wise in the use of it. May you seek after, and attain, every one of you, unto wisdom.

"The Lord bless you and keep you.

"The Lord make His face to shine upon you and be gracious unto you.

"The Lord lift up His countenance upon you and give you peace."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

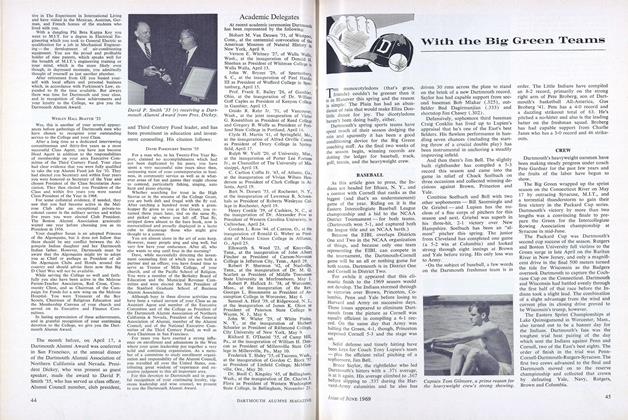

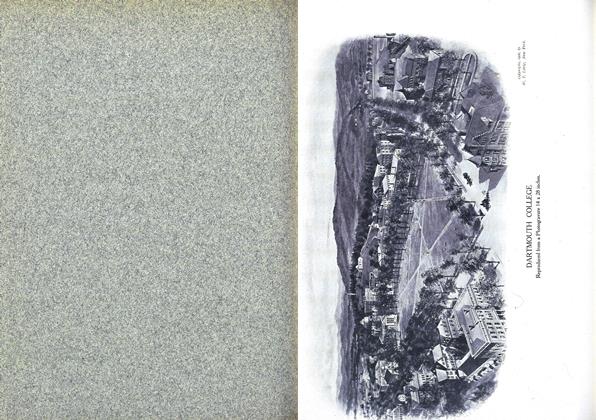

ArticleTHE MATERIAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE COLLEGE

August 1906 -

Article

ArticleWALT WHITMAN AND DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

August 1906 By ELIZABETH PORTER GOULD -

Article

ArticleTHE CONFERRING OF DEGREES

August 1906 -

Article

ArticleONE HUNDRED AND THIRTY-SEVENTH COMMENCEMENT OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

August 1906 -

Article

ArticlePHI BETA KAPPA ADDRESS BY THE HONORABLE ANDREW D. WHITE, LL.D

August 1906 -

Article

ArticleADDRESS OF MELVIN O. ADAMS, ESQ., PRESENTING THE NEW DARTMOUTH HALL IN BEHALF OF THE ALUMNI

August 1906