IN the annual Commencements of American colleges, perhaps no more striking or original personality ever appeared before such than he who came from his employment in the attorney general's office in Washington to deliver the Commencement Poem before Dartmouth College on June 26, 1872. Known as Walt Whitman (to distinguish him from his father Walt), he had published in Brooklyn in 1855, at the age of thirty- six (he himself assisting to set the type), a thousand copies of a book of about one hundred pages, when it appeared, "aroused such a tempest of anger and condemnation everywhere" that in his own words he said, "I went off to the east end of Long Island and spent the late summer and all the fall—the happiest of my life—around Shelter Island and Peconic Bay. Then I came back to New York with the confirmed resolution, from which I never afterwards wavered, to go on with my poetic enterprise in my own way, and finish as well as I could."

He had so persisted in this determination even through persecution and misunderstanding that the year before his appearance at the College five editions of this " great primitive poem," as Thoreau called it, had been published. Still holding the name he gave it, "Leaves of Grass," it was then enlarged by some of his poems which have come to be called his masterpieces, such as "Passage to India":

" Passage, indeed, O soul, to primal thought

To realms of budding Bibles

To reason's early paradise, Back, back to wisdom's birth, to innocent intuitions."

In this work, he declared'that after " many manuscript doings and undoings," in which he had "great trouble in leaving out the stock poetical touches," he felt he had succeeded at last.

To realize the poet's feeling that in celebrating himself, the "Adamusof the nineteenth century," the "Kosmical man" (not an individual, but mankind), he was celebrating "Uni- versal Humanity in its attributes," he had made himself familiar, either through experience, or the intuitions of genius, with all phases of our common humanity. His ego was not Walt Whitman as such, but the American ego—the flight of the universal soul.

"I fly the flight of the fluid and swallowing soul." (1855)

"Within me latitude widens, longitude length- ens." (1856)

"Through me many long dumb voices ... Through me forbidding voices ... Voices veiled, and I remove the veil."

Toward such a result, the poet had powerfully and unequivocally felt his own mission.

"I announce the great individual, fluid as nature, Chaste, affectionate, compassionate, fullyarmed." (1860)

"I announce a life that shall be copious, vehement, spiritual, bold. I announce an end that shall lightly and joy- fully meet its translation."

This broad view of life was what made his loyal follower, John Addington Symonds, say, that "speaking of Walt Whitman was like speaking of the universe"; that caused William Clark to say, in his "Study of the Poet," that he was "America's voice; not the voice of transcendental liberalism like Lowell, nor of a softened and humanized Puritanism like Whittier, nor an echo of England and Spain like Irving and Longfellow, but the voice of the average American spread over a vast and still rugged continent flushed with life, energy, and hope. His task was to foreshadow the future of the democratic life there, to announce things to come."

The year before (1871) had appeared his profound prose work "Democratic Vistas," in which he had declared that he looked forward "to poets not only possessed of the religious fire and abandon of Isaiah, luxuriant in the epic talent of Homer, or for proud characters as in Shakespeare, but consistent with the Hegelian formulas, and with modern science." He was positive in his assertion that "Faith, very old, now scared away by science, must be restored, brought back by the same power that caused her departure, restored with new sway, deeper, wider, higher than ever." He had published the soul-stirring "Pioneers":

"Have the elder races halted? Do they droop and end their lesson, wearied, over there beyond the seas ? We take up the task eternal and the burden and the lesson, Pioneers! O Pioneers. O you daughters of the West! O you young and elder daughters ! O you mothers, and you wives ! Never must you be divided, in our ranks you move united Pioneers! O Pioneers!" etc.

And now by invitation of the United Societies of Literary Endeavor this original and much-maligned poet appeared at the College to deliver the Commencement Poem. He had paused on the way (107 North Portland avenue, Brooklyn) to visit his mother in her home ("the best and sweetest woman I ever saw and ever expect to see") where he had attended to details concerning the publication in a small book-form of the poem to be delivered.

Doubtless it was a surprise to many that he should be invited to give the poem. Though well-appreciated by Tennyson, William Michael Rossetti, who some years before had published "Selections" from his writings which had resulted in Mrs. Anne Gilchrist's "A Woman's Estimate" (1870), Dowden, Swinburne, and other leaders across the sea, he was not a welcome leader here among the people. He had not been blessed with a college education, but he had taught school in his youth ("boarded round.") He had edited the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, the Freeman, and the daily Crescent of New Orleans. He had been an extensive reader of the best books. He himself tells us that, in hi - early life, he went off sometimes for a week at a time, in the country or by the seashore, there in the presence of outdoor influences, to read thoughtfully the Old and New Testaments, and to absorb (" probably to better advantage for me than in any library or indoor-room —it makes such difference where you read") Shakespeare, Ossian, Homer, Sophocles, Æschylus, Hegel, Dante, German Niebelungen, Hindoo poems, Don Quixote, etc., etc.

His abstracts of books and lectures had revealed the observing mind. His "Proud Music of the Storm" (1870) and other' poems had told of his wide acquaintance with music-life. His travels up the Mississippi, the Missouri, around the great lakes, Michigan, Huron, and Erie, to Niagara Falls and Lower Canada, down the Hudson, back to New York, had been an education to him. He had made himself familiar, as his biographer, Doctor Bucke, tells us, with "powerful uneducated persons," with "all kinds of employments, not by reading trade reports and statistics, but by watching and stopping hours with the workmen (often his intimate friends) at their work." He had visited the "foundries, shops, rolling- mills, slaughter-houses, woolen and cotton factories, shipyards, wharves, and the big carriage and cabinet shops." He had been to "clambakes, races, auctions, weddings, sailing and bathing parties, christenings, and all kinds of merry-makings." He had found the New York omnibus drivers good comrades, having declared that "these rough, good-hearted men" (like the Broadway stage-driver in "To Think of Time") had "undoubtedly entered into the gestation of ' Leaves of Grass.'" As to his character, while " going around with the so-called roughs," Peter Boyle, a street car conductor whose comradeship he enjoyed for years, has said in his published letters, "In his habits he was very temperate. He did not smoke. . . He seemed to have a positive dislike for tobacco. He was a very moderate drinker... I never knew a case of Walt's being bothered up by a woman. In fact, he had nothing special to do with any woman except Mrs. O'Connor and Mrs. Burroughs. His disposition was different. Women in that sense never came into his head. Walt was too clean, he hated anything which was not clean. No trace of any kind of dissipation in him; and," he concludes, "I ought to know about him those years—we we were awful close together."

Walt's words to this conductor reveal the sincere comradeship between the two. "Whatever happens," he wrote in 1870, "in such ups and downs, you must try to meet it with a stout heart. As long as the Almighty vouchsafes health, strength, and a clear conscience," let other things do their worst." Later he wrote, "The true point to attain, is, like a good soldier or officer, to keep on the alert, to do one's duty fully without fail— and leave the rest to God Almighty."

It was to this same Peter Boyle that the poet wrote from Hanover, Thursday, June 27, 1872, the day after he had delivered the poem, "All went off very well," he said, "though it was rather provoking," that having felt unusually well the whole summer, for a few days he had been "about half sick," and was so "yet by spells." After a couple of days in Vermont, he hoped to be back in Brooklyn, when he would send him the little book with the College poem and others. If the poem appeared in the Washington papers—the Chronicle or Patriot, he would like a copy of each. "It is a curious scene here," he concludes, " as I write, a beautiful old New England village, one hundred and fifty years old, large houses and gardens," great elms, plenty of hills—everything comfortable, but very Yankee—not an African to beseen all day—not a grain of dust—not a car to be seen or heard, green grass everywhere—no smell of coal tar." While he was writing, he said that baseball was being played on a large green in front of the house. The weather suited him first rate—"cloudy but no rain." He signs himself, "Your loving Walt."

As I write these lines, there lies by my side a copy of the book, dated 1872, which published the poem as given that Commencement Day. It was found in the "den" when the poet died. Its title is the name he gave it, "As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free." Besides this poem of one hundred and thirteen lines, there are several other poems, including " The Mystic Trumpeter," and some closing notes concerning the poet's works. In the five-page preface to this first installment of the book, he says it was "pencilled in the open air, on his fifty-third birthday, wafting to you, dear reader, whoever you are, from amid the fresh scent of the grass, the pleasant coolness of the forenoon breeze, the lights and shades of tree-boughs silently dappling and playing around me, and the notes of the cat-bird for undertone and accompaniment—my good-will and love.'' This was written in Washington, less than a month before he appeared at Dart- mouth. In it he declared he was still convinced of the power of his book, that in its intentions it was the "song of a great composite Democratic Individual, male or female, and, if ever completed, there would run through the chants of the volume the thread-voice, more or less audible, of an aggregated,inseparable, unprecedented, vast, composite, electric, Democratic Nationality."

Opening to the poem as delivered that June day, beginning:

" As a strong bird on pinions free, Joyous, the amplest spaces heavenward clearing," etc. and ending with: " Thou mental, moral orb! Thou new, indeed new spiritual world, The present holds thee not." etc.,

I am reminded of Doctor Bucke's confession, that it was eighteen years after he had first read the poem (when he threw the book across the room) before, he fully entered into its spirit. Then he declared his feeling towards Walt Whitman for the " more or less continuously higher plane of existence" he had vouchsafed to him, had become "one of the deepest affection and reverence."

I had heard of other like testimonies, one especially told me by Mellen Chamberlain when librarian of the Boston Public Library. He said that while waiting for a friend in a reception room of a London hotel, he took up a book on the table to read. It was none other than "Leaves of Grass, " which he had not seen. He did not do what too many do on first meeting the book, hunt up a few condemned lines and judge all by such, but he opened at random to a poem now considered one of the poet's finest productions. But even as an extensive lover of the world's best literature, he saw no form or comeliness in it. A continuous reading did not help him. At last he became so impatient that he, too, threw the book across the room. Feeling somewhat troubled at so treating the work of his own countryman, he picked it up, laid it on the table, and reflected until his friend arrived. Some time afterwards, the Poems with the autobiographical prose work, "Specimen Days and Collect," came into his hands in his American home. Happening to take up the prose work first, he became so interested in the personality, the originality of the poet, that he was led to take up the "Poems." He found himself reading the lines over and over again. Day after day he continued the reading; and a short time before his death he declared with earnestness that, while not free from faults, which all sane Whitmanites acknowledge, Walt Whitman was " a great, elemental, pioneer force, not to be ignored in the history of literature or democracy." He came to find delight in reciting marked poems, and in adding autograph-letters and pictures to his collection of such in the Boston Public Library. He came to acknowledge with John Burroughs, that the poet kindled in him the delight he had, "in space, freedom, power, the elements, the cosmic, democracy, and the great personal qualities of self-reliance, courage, candor, charity," etc.

Doubtless some of the students of that Commencement time have had a similar experience to this of Mellen Chamberlain, who, as is well-known, is a Dartmouth alumnus, has honored and been honored by the College. But whether so or not, they must that day have been struck with the personality of the man, with his robust figure six feet tall, weighing nearly two hundred pounds, a finely-shaped head, full brow, blue eyes, and a somewhat red face, with a gray full beard. Dressed, as an eye witness (a daughter of one of the professors) tells us, in a flannel shirt with a broad collar, making bare the neck, he doubtless shocked those bound to the conventional. But in spite of this seeming affectation of dress, adopted at the time, he adopted his literary style not so much to be eccentric as to reveal a natural antagonism to mere show or sham (his brother, George, says he was "rather stylish when young, being conventional in dress as in the verses and stories he wrote.") The seeing eye must have noted the " naturally majestic stride " of the man, "a massive model of ease and independence," suggesting " infinite leisure;"—a personality which had caused Abraham Lincoln upon first seeing him to exclaim, "Well, he looks like a man." The seeking soul must have felt what Walt ever felt when in the presence of young men:

"Camerado, I give you my hand! I give you my love more precious than money. I give you myself before preaching or law; Will you give me yourself? Will .you come travel with me ?"

Should not a man of such power and vision have been warmly welcomed by any body of people seeking truth and progress ? But though already called the " good, gray poet " by his loyal friend William D. O'Connor, and loved by a devoted few, he had not come to his own—the heart of the American people. The Washington Chronicle, or the Patriot, did not notice the even). The DailySpring-held Republican, though publishing the poem, June 27, felt obliged to say in its account of the Commencement, that Walt Whitman being introduced read his poem, "As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free," in which "America's freedom and strength were set forth in the poet's own peculiar style, much to the disappointment of the expectant audience." But in spite of this, the young men of Dartmouth were now honoring him. It was his first -experience before a college. The year before, September 7, 1871, at noonday, by invitation of the American Institute in New York City, he had delivered his " After All Not to Create Only" (now found in his " Song of the Exposition")—a line which had become familiar to his comrades for having been the welcome salute of General Garfield ever since he had met him some years before. But that was in "The Rink," a two-acre edifice on Third Avenue, midst "crowded examples of machinery, goods," etc. Here he was before a time-honored institution, with its classic surroundings. From the time when,pa child of five, Lafayette with a kiss had lifted him up from a crowd of children to a safe spot where he could witness the laying of the corner-stone of the Apprentice Library in Brooklyn, literary surroundings had more or less claimed his attention. He knew the power of the poet's mission, for had he not written (1860) —"The true poets are not followers of beauty, but the august masters of beauty." He had revealed his love for nature in all its forms, loving the "Splendor of ended day floating and filling me" ... " The white arms out in the breakers tirelessly tossing "... " The bustle of growing wheat," etc.

He had lived his life among the soldiers—

"Upon this breast has many a dying soldier leaned to breathe his last."

He had written his " Captain, O My Captain," in which he had personified Death with "its superb vistas."

"I chant a song for you, O sane and sacred Death ... Come lovely and soothing Death ... O vast and well-veiled Death ... The sure-enwinding arms of cool-enfolding Death."

He had made a large horizon for him- self in thought and religion—

"As base and finale too for all metaphysics, I see underneath Socrates . . . and underneath Christ," the divine—

"No character nor life worthy the name with- out religion,"

"No land nor manor woman without religion."

And now he was bringing to these young students, not the "conceits of the poets of other lands," not the "compliments that have served their turn so long,” not the rhyme—nor the classics—nor perfume of foreign court, or indoor library, but an odor as from forests of pine in the North, in Maine, or breath of an Illinois prairie, "With open airs of Virginia, or Georgia, or Tennessee, or from Texas uplands, or Florida's glades, With presentment of Yellowstone scenes in Yosemite, And murmuring under, pervading all, I'd bring the rustling sea-sound That endlessly sounds from the great seas of the world."

To this he also brought his latest thought concerning the Union.—

... thou transcendental Union! By thee Fact to be justified—blended with Thought."

He saw there were to arise in this " Land in the realm of God to be a realm unto thyself Under the rule of God, ... ... three peerless stars To be thy natal stars, my country, Ensemble, Evolution, Freedom, Set in the sky of Law."

For a better understanding of this profound, originally-expressed thought, the students doubtless needed the fuller illumination of study. But that it was heard as a seed-sowing from a poet who had not come to his own, was a compliment to Dartmouth College, an honor to be more and more appreciated as time goes on.

Two years from that time, on the afternoon of June 17, 1874, by invitation of the Mathetican Society, more of Walt Whitman's thought was given at another Commencement, that of Tufts College, then under the presidency of Doctor Alonzo A. Miner. The poet being ill, it was read by the Professor of Elocution, Moses True Brown ;—and under the title " A Chant of the Universal " (now known as "The Song of the Universal") was printed in The Universalist of July 4, 1874.

" All, all for immortality— Love like the light silently wrapping all, Nature's amelioration blessing all. Give me, O God, to sing that thought, Give me, give him or her I love, this quenchless faith, In Thy ensemble, whatever else withheld, with-hold not from us Belief in plan of Thee, enclosed in Time and Space, Health, peace, salvation, universal."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

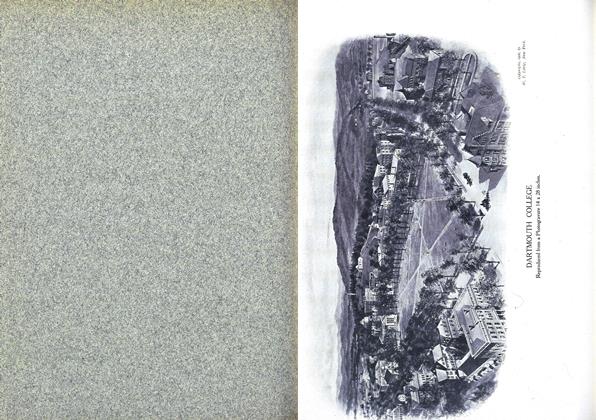

ArticleTHE MATERIAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE COLLEGE

August 1906 -

Article

ArticleTHE PRESENT CALL TO WISDOM

August 1906 -

Article

ArticleTHE CONFERRING OF DEGREES

August 1906 -

Article

ArticleONE HUNDRED AND THIRTY-SEVENTH COMMENCEMENT OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

August 1906 -

Article

ArticlePHI BETA KAPPA ADDRESS BY THE HONORABLE ANDREW D. WHITE, LL.D

August 1906 -

Article

ArticleADDRESS OF MELVIN O. ADAMS, ESQ., PRESENTING THE NEW DARTMOUTH HALL IN BEHALF OF THE ALUMNI

August 1906