THE PH.D. DEGREE

To THE EDITOR OF THE DARTMOUTH BI-MONTHLY :

In the leading editorial of your last number you speak of the preceptorial system as a " reaction in American education against the advance of German methods and the spirit of fetichism towards the Ph.D. degree." This statement seems strange to one who looks carefully at the facts, or who. reads the excellent article of Mr. Gerould in the same number. The fact is that of the forty-eight new preceptors, thirty-five are Ph.D.s, and of these at least five are the unadulterated product of German methods. The remaining thirteen, for a period of more than. two years apiece on the average, have studied in the stimulating atmosphere of Graduate Schools, which is as different in quality and effect from the atmosphere of ordinary undergraduate life as that of Panama and Pike's Peak. There they were touching elbows with scholars; there they were learning to share the ideals and enthusiasm of other men who had the ambition, persistence, and ability which are necessary to Secure the Ph.D. degree; and although these thirteen were unable to complete all the requirements and actually take the degree, they have had, side by side with men who were to become Ph.D.s, a large amount of real graduate training (which after all is the essential thing), and deserve to be classed rather with Ph.D.s than with those teachers " who are to be forgiven the lack of that final increment of knowledge which some deem so all-important." A group of men, three-fourths of whom are Ph.D.s and all of whom have had Ph.D. training, scarcely seems to be a reaction against the Ph.D. degree.

In the matter of German methods, is the editorial more accurate? The two main features of German university education are lectures and socalled “seminars.” In the first place, as to the lectures, the most striking thing about them (except those of a Harnack, Paulsen, Schmoller, or Erich Schmidt, which are the exceptions proving the rule) is that they are of so little importance. So well is this recognized by the students themselves that, though two hundred youths may present themselves on the first and last day of the course to get the professor's signature as an indication that they have "taken" the course, the average daily attendance will not fill a hundred seats. No penalty is inflicted for non-attendance; not even a list of absences is kept; and there is no examination at the close of the course. Now the new plan at Princeton seems also to aim to lessen the relative importance of lectures; it is thus, in regard to lectures, an approach to the German ideas rather than a reaction from them. In the seminar, on the other hand, ordinarily a dozen students gather once a week around a professor to study together a common topic. A student will present a report on some phase of the topic; he will have prepared thoroughly, for he knows he must stand a fire of questions from his fellows as well as from the professor. The interest in the subject is so intense and the value of the training so great that students do not "cut" seminars. Nor is there any thought of marks, of reciting, or of "passing the course," only of truth for its own sake. If a disputed point arises, books are pulled down from the shelves of the library where the seminar meets, and all work together under the professor's guidance to settle the question on the spot. Thus, the whole tendency of the seminar is "to emphasize books and the professor in their relation to the individual student," which, according to Mr. Gerould, is precisely the characteristic of the preceptorial system. Far from being a reaction against German methods, the Princeton system looks almost more like an attempt to adapt and introduce the German graduate seminar into American undergraduate work.

It is not, however, your conception of the preceptorial system against which I wish to protest, but your belittlement of the Ph.D. degree. "Without wishing to disparage the value of such a degree," you proceed to do so most seriously. "That the degree has helped many men to secure teaching positions who have no ability to teach " may occasionally be true, but so have engaging manners, church membership, fraternity backing, political pull, or a dozen other things which one might mention. Even the A.B. degree is partly sought for the sake of the better position which its holder hopes to command. That there may be Ph.D.s in teaching positions who cannot teach is purely the fault of those who employed them to teach. For the practice of the profession of law. or medicine we require a degree or certificate which evidences a certain careful training. But if the lawyer has too squeaky a voice or the doctor too little common sense for successful practice, we simply do not employ him. We do not find it necessary to disparage his course of training nor belittle his profession. Ido not by any means wish to contend that every member of a college faculty should hold a Ph.D. degree; in view of the many splendid teachers, young or old, who are not Ph.D.s, such a contention would be ridiculous. But I do insist that we should regard college teaching essentially as a profession, similar to law or medicine, and expect of those who practice it a proper preparation. And I do believe that, though exceptions may occasionally be made, in making new additions to its faculty, it is ordinarily for the best interests of any college to demand of its teachers evidence of a careful and exact preparatory training. There is no better evidence than the Ph.D. degree.

Yours very truly,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE AMOS TUCK SCHOOL

April 1906 By Harlow S. -

Article

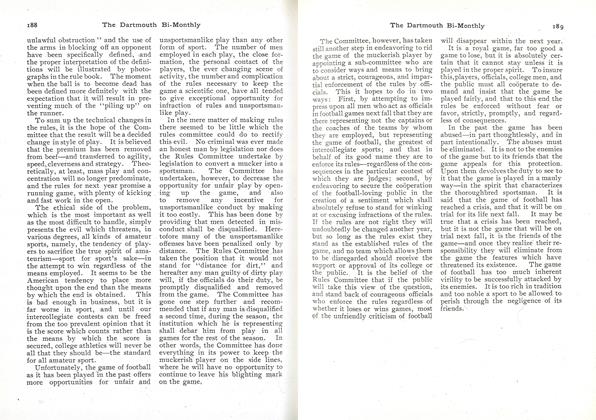

ArticleTHE FOOTBALL RULES OF THE NEXT SEASON

April 1906 By E. K. Hal '92 -

Article

ArticleAT a meeting of the Faculty early in the year the following vote

April 1906 -

Article

ArticleFIRST TRICOLLEGIATE LEAGUE DEBATE

April 1906 -

Article

ArticleTHE SUPPLEMENT TO THE GENERAL CATALOGUE, AND SOME OF ITS FACTS

April 1906 By Charles F. Emerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1887

April 1906 By Emerson Rice