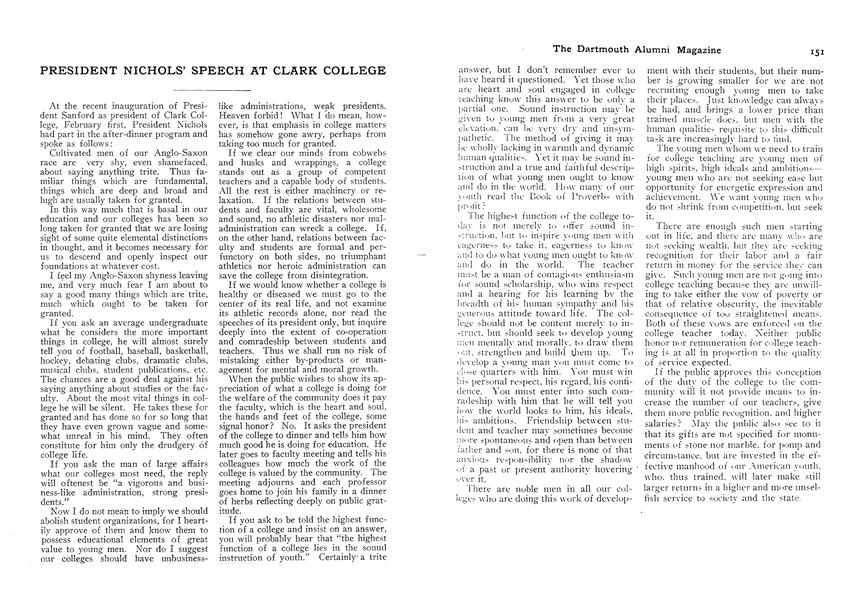

At the recent inauguration of President Sanford as president of Clark College, February first, President Nichols had part in the after-dinner program and spoke as follows:

Cultivated men of our Anglo-Saxon race are very shy, even shamefaced, about saying anything trite. Thus familiar things which are fundamental, things which are deep and broad and high are usually taken for granted.

In this way much that is basal in our education and our colleges has been so long taken for granted that we are losing sight of some quite elemental distinctions in thought, and it becomes necessary for us to descend and openly inspect our foundations at whatever cost.

I feel my Anglo-Saxon shyness leaving me, and very much fear I am about to say a good many things which are trite, much which ought to be taken for granted.

If you ask an average undergraduate what he considers the more important things in college, he will almost surely tell you of football, baseball, basketball, hockey, debating clubs, dramatic clubs, musical clubs, student publications, etc. The chances are a good deal against his saying anything about studies or the faculty. About the most vital things in college he will be silent. He takes these for granted and has done so for so long that they have even grown vague and somewhat unreal in his mind. They often constitute for him only the drudgery of college life.

If you ask the man of large affairs what our colleges most need, the reply will oftenest be "a vigorous and business-like administration, strong presidents."

Now I do not mean to imply we should abolish student organizations, for I heartily approve of them and know them to possess educational elements of great value to young men. Nor do I suggest our colleges should have unbusinesslike administrations, weak presidents. Heaven forbid! What Ido mean, however, is that emphasis in college matters has somehow gone awry, perhaps from taking too much for granted.

If we clear our minds from cobwebs and husks and wrappings, a college stands out as a group of competent teachers and a capable body of students. All the rest is either machinery or relaxation. If the relations between students and faculty are vital, wholesome and sound, no athletic disasters nor maladministration can wreck a college. If, on the other hand, relations between faculty and students are formal and perfunctory on both sides, no triumphant athletics nor heroic administration can save the college from disintegration.

If we would know whether a college is healthy or diseased we. must go to the center of its real life, and not examine its athletic records alone, nor read the speeches of its president only, but inquire deeply into the extent of co-operation and comradeship between students and teachers. Thus we shall run no risk of mistaking either by-products or management for mental arid moral growth.

When the public wishes to show its appreciation of what a college is doing for the welfare of the community does it pay the faculty, which is the heart and soul, the hands and feet of the college, some signal honor? No. It asks the president of the college to dinner and tells him how much good he is doing for education. He later goes to faculty meeting and tells his colleagues how much the work of the college is valued by the community. The meeting adjourns and each professor goes home to join his family in a dinner of herbs reflecting deeply on public gratitude.

If you ask to be told the highest function of a college and insist on an answer, you will probably hear that "the highest function of a college lies in the sound instruction of youth." Certainly a trite answer, but I don't remember ever to have heard it questioned. Yet those who are heart and soul engaged in college teaching know this answer to be only a partial one. Sound instruction may be given to young men from a very great elevation, can be very dry and unsympathetic. The method of giving it may be wholly lacking in warmth and dynamic human qualities. Yet it may be sound instruction and a true and faithful description of what young men ought to know and do in the world. How many of our youth read the Book of Proverbs with profit?

The highest function of the college today is not merely to offer sound instruction, but to inspire young men with eagerness to take it, eagerness to know and to do what young men ought to know and do in the world. The teacher must be a man of contagious enthusiasm for sound scholarship, who wins respect and a hearing for his learning by the breadth of his human sympathy and his generous attitude toward life. The college should not be content merely to instruct, but should seek to develop young men mentally and morally, to draw them out, strengthen and build them up. To develop a young man you must come to close quarters with him. Yon must win his personal respect, his regard, his confidence. You must enter into such comradeship with him that he will tell you how the world looks to him, his ideals, his ambitions. Friendship between student and teacher may sometimes become more spontaneous and open than between father and son, for there is none of that anxious responsibility nor the shadow of a past or present authority hovering over it.

There are noble men in all our colleges who are doing this work of development with their students, but their number is growing smaller for we are not recruiting enough young men to take their places. Just knowledge can always be had, and brings a loweer price than trained muscle does, but men with the human qualities requisite to this difficult task are increasingly hard to find.

The young men whom we need to train for college teaching are young men of high spirits, high ideals and ambitions— young men who are not seeking ease but opportunity for energetic expression and achievement. We want young men who do not shrink from competition, but seek it.

There are enough such men starting out in life, and there are many who are not seeking wealth, but they are seeking recognition for their labor and a fail return in money for the service they can give. Such young men are not going into college teaching because they are unwilling to take either the vow of poverty or that of relative obscurity, the inevitable consequence of too straightened means. Both of these vows are enforced on the college teacher today. Neither public honor nor remuneration for college teaching is.at all in proportion to the quality of service expected.

If the public approves this conception of the duty of the college to the community will it not provide means to increase the number of our teachers, give them more public recognition, and higher salaries? May the public also see to it that its gifts are not specified for monuments of stone nor marble, for pomp and circumstance, but are invested in the effective manhood of our American youth, who, thus trained, will later make still larger returns in a higher and more unselfish service to society and the state.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleIn describing the successful working

February 1910 -

Article

ArticleTHE OEDIPUS TYRANNUS OF SOPHOCLES AT DARTMOUTH

February 1910 -

Article

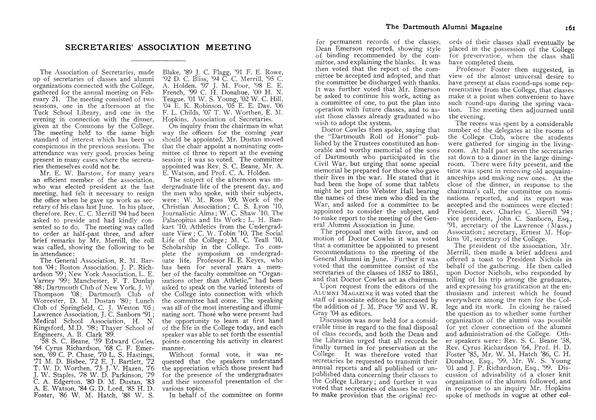

ArticleSECRETARIES' ASSOCIATION MEETING

February 1910 -

Article

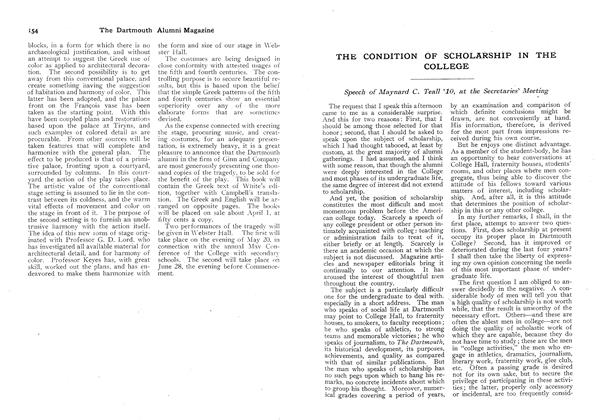

ArticleTHE CONDITION OF SCHOLARSHIP IN THE COLLEGE

February 1910 By Maynard C. Teall '10 -

Class Notes

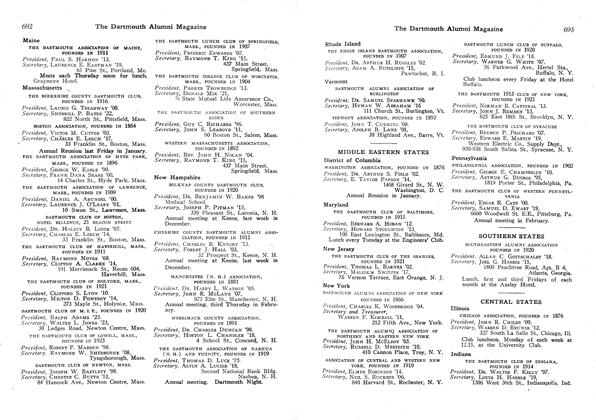

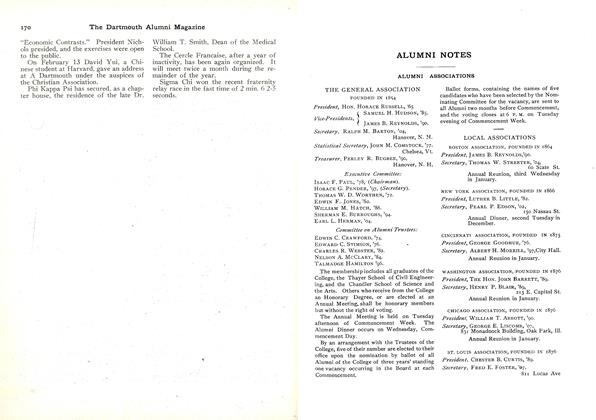

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

February 1910 -

Article

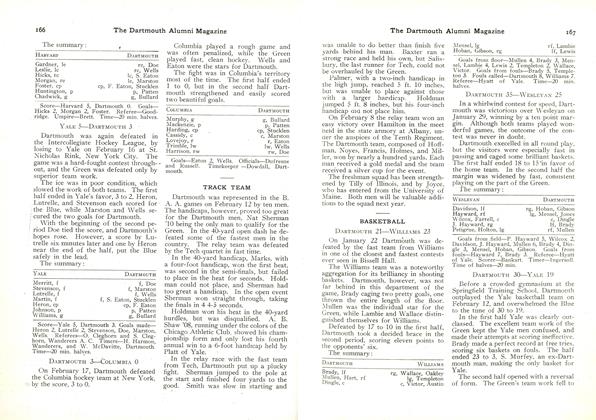

ArticleBASKETBALL

February 1910