The first meeting of the Alumni Council held at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia, November 7 and 8, established a new mark in the progress of Dartmouth; for as the conference developed it became constantly clearer that the men who had gathered from all parts of the Union as representatives of the great alumni body had come not so much for the purpose of assuming authority, as of accepting responsibility for themselves and for those whom they represented.

This was evident not merely from what was said but from what was left unsaid; not merely from what was done but from the way of doing. The first regular session lasted from seven-thirty in the evening until close to midnight; the second from nine in the morning until nearly noon. And during the entire period the purpose of this first meeting to establish principles rather than to consider details was never lost sight of.

To determine the function of the alumni, or, at least, to come to some common agreement as to their function, was from the first recognized as fundamental. The program committee had had this in mind in arranging the order of exercises for the meeting. Friday evening the committee had set apart for speeches calculated to bring to bear a variety of viewpoints: that of the admin- istration ; that of the trustees; that of the faculty; and that of the alumni. Out of the richness of his experience and judgment Dr. Tucker had been asked to contribute to the program.

Once the Council had come to some agreement as to its due reason for being, the program committee had wisely foreseen that the steps toward organizing to make that reason effective would require considerable deliberation. For this, Saturday morning had been appointed.

When the meeting finally adjourned, the Council was agreed as to the work before it, and was organized to undertake it.

The roll call showed twenty out of twenty-five present. On Saturday morning another had been added to the list. Of those absent, one was from Nebraska, one from Texas, and two from California, all detained for sufficient reasons.

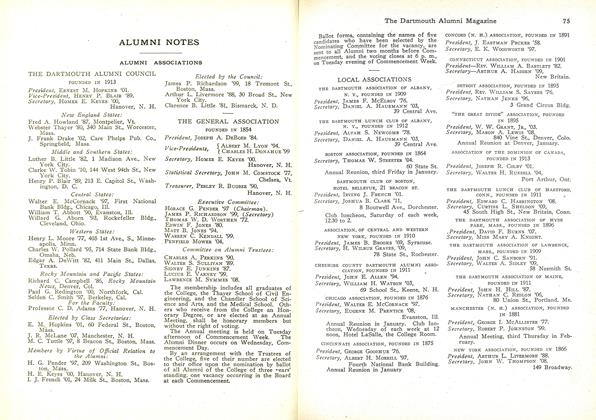

The election of officers was the first piece of business to be transacted. E. M. Hopkins .'01 of Boston was made president, H. P. Blair '89 of Washington was made vice-president, and Homer E. Keyes 'OO of Hanover was made secretary-treasurer.

The program of addresses was then opened; the topic being that of "The Function of the Alumni of Dartmouth College". President Nichols had been asked to speak for the administration.

PRESIDENT NICHOLS

President Nichols confined himself to a few pithy statements. At the outset he declared that the alumni are "the end, the aim, and the means of the College". The College exists in order to turn out men, men of trained abilities, who, in turn, will render aid to the College in educating those who come after. Founded as the ideal of an individual, governed at first by one man, Dartmouth had grown to the point where it was no longer to be controlled as a monarchy, or as an empire, but as a republic. He welcomed the wider participation of the alumni in assuming the responsibilities which the College must encounter.

The President went on to speak of the various needs, both of the College and of the alumni, which the Council might help to meet. He touched very little upon the financial aspects of the case, but contented himself with a consideration of the larger aspects of the Council as a body of influential men capable of affecting sentiment within the College and without; and of assisting in a multitude of ways in maintaining the ideals and fulfilling the purposes of Dartmouth.

MR. MATHEWSON

For the Trustees Mr. Mathewson spoke. He pointed out what valuable work alumni organizations of other institutions were doing. Particular emphasis he laid upon the work of the Yale Alumni Council in raising money for university purposes. He read at some length from reports of the Yale Council, and showed how that body, starting in 1891 with total alumni contributions of $5,000, had raised the same to $60,000 in 1913, having in the meantime added more than half a million dollars to the permanent funds of the University.

Mr. Mathewson stated that the success of any college must depend upon its alumni, and "that he had no doubt that Dartmouth men could and would equal Yale's record, provided the right machinery for handling the project were put in motion.

PROFESSOR ADAMS

Professor Adams made the statement for the faculty. He had written his remarks in advance, and at the unanimous request of the meeting, they are here reprinted. Professor Adams pointed out so clearly the responsibility of alumni for aspects of undergraduate life, that there was no escaping the truth of his observations. He said:

The New Dartmouth is the direct outgrowth of the enthusiastic service of the alumni. No college, of today in America is so completely the product of the love and sacrifice of its alumni as is Dartmouth College. Our phenomenal increase in students, our large endowment, our splendid new buildings, have come with few exceptions through the spontaneous uprising of the alumni under great leadership. By their control of the Board of Trustees the alumni have official control of every department of the College today. But we are not content with what has been done. We have the feeling that we have only begun to realize the possibilities of an institution that has its devoted sons in every influential community in the land. The Alumni Council seeks to develop this latent power. You ask me to tell you what possibilities the Faculty see in such organized support by the alumni.

It is a truism to say that the college must develop every student on three sides, the intellectual, the moral, and the physical. We agree also that in each of these departments of education it is lasting power that we are to seek, rather than immediate attainments; that is, that in the intellectual field we are to seek mental ability, the development of real intellectual power, rather than bulk of present information; that in the moral field a sound character, self-governing power, is more important than correct moral habits imposed by external constraint; that in the physical field sound health and harmonious development are more to be sought than the development of special sets of muscles or ability to do some particular physical thing. In all these fields we look toward the man's future, and seek that development in all three that will be productive in the long years, not merely attractive now.

By the action of the Trustees one of the three fields, the physical, has been committed almost wholly to the alumni. The alumni have responded generously and enthusiastically. I need not, therefore, dwell on this relation of the alumni to the College—it is one of the most important ones, but it is specifically their own. I will turn at once to the two fields that have been entrusted definitely to the Faculty. What then is the relation of the alumni to the intellectual life of the College, as the Faculty view the situation?

Up to a certain point the Faculty, under the leadership of the President, control the intellectual life of the College. They say what intellectual attainments shall be demanded for admission. They provide in College the opportunity for acquiring a certain body of knowledge. And this is indispensable. Life in the twentieth century is so complex that an intelligent man demands for himself a considerable body of facts and tools as an outfit for rational living. The college faculty offer to the student a large body of these indispensable facts in History, Science, Literature, Art; they offer him also in foreign languages, ancient and modern, the tools of intelligent reading. The faculty insist through their machinery of marks and discipline on a certain minimum of acquirement of such bare knowledge. But they look on this as subordinate; the power to think is their higher aim; a disciplined judgment and a real love for things of the mind are their ultimate concern. They seek to cultivate these high qualities by all the means in their power; they insist on regular habits of study, as indispensable to the development of mental power; they offer honors and prizes to men who show the highest mental ability; they award graduate fellowships to the men who show greatest promise. But these external, concrete means are not very effective, and, most serious fact of all, they fail to reach in any strong way the great middle mass of the student body. To quicken and develop the intellectual life of the ordinary man is the hard problem of the faculty. It is easy to drop the laggard, or to prod him just inside the ranks; it is easy to stimulate the genius, who is already stimulated by his own intellectual tastes and ambitions; but to make the great mass of the college care for the intellectual life—there is the problem. For the average boy comes to college today without any very definite intellectual ambition. More than half expect to go into business. They know that a college degree is of great value in getting a start; they want the degree. They know that certain of the by-products of college life are immensely valuable in business—the ability to get on with men, the power to direct men and to carry enterprises to success, the power to see things from other men's point of view; all these things will be valuable to them, and they seek them where they are best found, on the campus, in the fraternity house, on the athletic field; a certain amount of knowledge too in economics and political and social science is so manifestly necessary that they willingly put themselves in the way of acquiring it; but beyond that? The rest is so much grind—so many barriers set up by an arbitrary college faculty between them and their degree. Other men, aiming at some of the professions, have something of the same attitude; only what contributes directly to preparation for their own professional school is tolerable to them, and that only as a means to an end.

Again, a good many men who come to college with a considerable degree of intellectual curiosity and intellectual ambition find themselves diverted the multiplicity of side issues in college life; they are plunged into a social group in which there are so many delightful, useful, admirable diversions and enterprises of every sort that seven days in a week will not begin to give a bright man time enough to take part in all of them. Will the intellectual life of the immature boy, thrown for the first time on his own resources, stand this strain, or shall we find him after a little time looking on the intellectual part of college life as the daily grind, to be put out of the way .with only so much effort as is demanded, and the outside activities as the things of real value?

Can the college somehow surround this boy with such an all pervasive intellectual atmosphere that he shall after all feel that to know and to think are the high objects of ambition?

We of the faculty can do something toward creating this atmosphere that is so essential, if your sons are to feel a great stimulus to the intellectual life. You have a right to expect that we will ourselves show a devotion to scholarly pursuits that shall attest our own appreciation of them; you have a right to expect that we will give to our students the stimulus of contact with men of our own number who are tasting the fine flavor of the discovery of truth; you have a right to ask that your sons see at Dartmouth important investigations going on that are furthering human knowledge; only so can they catch the contagion , of intellectual curiosity. We can and must also so present learning as to show its relation to life; we must vitalize it. But an atmosphere is a difficult thing to create; scholarly ideals are not easily communicated to young men ambitious for wealth or preferment, or fascinated by the immediate pleasures of social life.

How can the alumni help the faculty in this attempt to make the intellectual life the object of great desire on the part of your boys?

The individual alumnus can first of all show in his own life a fine example of the intellectual man. Wherever a Dartmouth alumnus stands out in his community as a man of sound judgment, a master of his profession, a lover of books, a leader among the thinking men of his town, he is helping create an atmosphere of scholarship in the Old College; for every undergraduate who knows him comes to us with something of the contagion, of a good example, with an ambition to become something better than a getter of dollars or snatcher of political" plums. These alumni, oftentimes quiet men, little known to the alumni body at large, are to be reckoned among the benefactors of the College.

Again the individual alumnus can help effectively, if in all his personal intercourse with undergraduates he lets them see that he is .himself deeply interested in the intellectual progress of the College. This is not always easy; the concrete things are more obvious, more easily talked about. As I talk with old college friends of my own I am impressed with the fact that for the most part they do measure the New Dartmouth in terms of new buildings, increase in the size of entering classes, prominence in the world of sport, rather than in progress in the things to which these are only the means. And yet that progress has been just as real, I think even greater in amount, than the progress in material things and in numbers. There has been intangible progress in the last three years that very few men know, progress that has great promise for the future of the College. Whenever an alumnus lets a college boy see that he is tremendously interested in the intellectual progress of the College, ambitious to see the College placed in the front rank of scholarship, he is helping in a very substantial way.

A third service that the individual alumnus can do the College is to seek out and send to Dartmouth the choice scholars of the schools. All over the country there are bright boys who are ambitious for an education, some of them undecided as to their college, more of them unable to see their way to going to college at all. If in every community where there are Dartmouth men we could be sure that the most promising scholars were being turned toward Dartmouth, boys who had more than made good in their schools, we should feel sure of the future of scholarship at Dartmouth. The Western schools especially are turning out boys of splendid parts and keen intellectual tastes and ambition, whom we need at Dartmouth to strengthen our scholarly ideals. We must not let the great universities monopolize the scholarly product of the schools. Our alumni would not consider the possibility of maintaining the athletic prestige of the College without the definite attempt to find all over the country men who have made good in one field or another of competitive athletics. You, like the alumni of every large college, try by every honorable means to search out these men and turn them toward Dartmouth. Your coaches have picked material at the start. As a result they have put Dartmouth into a position of leadership in athletics where she contests the honors with the best of the universities. But can you be content to have your college, that stands in the front rank in athletics, take a second rank in the fundamental thing for which every college exists, scholarship? Must you not treat your faculty as well as you treat your coaches? You certainly must if you are going to expect from them equally good results. If we are to make Dartmouth a place of high scholarship we must have our share of students of the best quality, men who are bright, ambitious, thoroughly trained in the best schools. Every alumnus who turns such a student to us is making a large contribution to the scholarship of the college.

The alumni can further serve the intellectual interests of the college by paying prompt honor to those of their own number who achieve success along scholarly lines. Success in business or in executive fields makes itself manifest; scholarly achievements are not so widely and so quickly known. Our alumni associations ought to be on the watch for the opportunity to reward scholarly achievement among their own number. It ought to be true that just so surely as a member of the New York Alumni Association publishes a worthy book, writes a brilliant article for a review, receives a professional promotion that is known to be based on sound achievement, his alumni association will give him instant recognition. He is the man who ought to be honored with office, to be heard at the alumni dinner, to be recommended for an honorary degree. Let the undergraduates see that the alumni bodies are watching the intellectual careers of their brethren; the effect will be real. Such recognition should be given especially to our younger alumni. We hear that one has received his A. M. at Columbia with distinction, another has won a graduate prize at Harvard, another has been made an instructor at Yale, that the researches of another are being talked of in the learned societies—I could name the men whom I have in mind—; all these should find recognition in alumni circles. The Alumni Magazine can be of great service here. One editor might well give his entire service to following the scholarly careers of the younger men; the material would be found in the class reports, in reports by heads of departments in the faculty—we have just had an admirable example of such a report in an article by Professor Bartlett in the Magazine—, and in notices in the press. Every publication by an alumnus should receive prompt review in the Magazine.

The alumni associations might well extend similar recognition to the members of the faculty who bring honor to the College by their discoveries. Two years ago Professor Patten brought out a book that marks an epoch in the discussion of one of the fundamental questions of biology. Whatever may be the final verdict as to his solution of the question of the origin of the vertebrates, his book will stand as one of the permanent contributions to knowledge in that field. It stands, too, for a beautiful devotion to the search for truth; the giving of a life to the testing of a great question that will bring not money, but knowledge; the ideal search of the scholar. It stands for years of laborious study, travel almost around the globe, large grasp of fundamental principles. Such an achievement marks the college as a worthy home for your boy. It ought to find large recognition from the alumni. We ought to be able to count upon instant recognition of every piece of fine, scholarly work on the part of a member of the faculty. Such an achievement should be followed by invitation to the alumni meetings and introduction to the members. The undergraduates would be quick to see the honor in which the alumni hold the scholar.

Would it be too much to say that now and then a brilliant undergraduate might well be the guest of an alumni association? The newspapers see to it that the names of our athletes are houseshold words in your homes; I wonder how many of you could name one of the leading scholars of our senior class? And yet there is hardly a year when we have not some man who would do honor to the college at any alumni meeting by a bright poem, or a speech on some college problem. Imagine the effect on the undergraduates if they should find scholarship so honored.

Finally, I think the Dartmouth alumni as a whole might before very longperhaps not just yet—be led into a great movement for the financial support of some specific intellectual interest of the College. I wish the new library building might stand as the gift of the whole alumni body. It would be a fitting testimony to' their faith in the world of books. Or the housing and endowment of a great department of instruction and research, like that of Chemistry, would be a fine embodiment of alumni appreciation of scholarship as the foundation of the College. This I should wish primarily for its influence on undergraduate sentiment, and its reflex influence on the alumni themselves.

You will see that in all that I have been saying I have been thinking of the possible work of the alumni in strengthening the sentiment for scholarship - scholarship in its widest and truest sense, not the mere amassing of information, but the development of the spontaneous and ambitious intellectual life, We must make the Dartmouth undergraduate feel that the college world revolves around the intellectual life. And this is something that cannot be done chiefly by administrative machinery; it is very largely a matter of college sentiment. Is it too much to ask that the alumni do their part in creating this sentiment?

But there is another field of college training in which the faculty need the help of the alumni: the development of character. A highly developed intellect without the virtues of self-control, of self-sacrifice, and of loyalty to great ideals is a poor product of any education. A college of Dartmouth's origin cannot conceive of such an educational aim.

And yet the moral discipline is even more intangible than the intellectual— the moral atmosphere something even more subtle. The childhood stage of morality, with its constant oversight and its specific prohibitions and penalties, is a thing of the past when your boy comes to college. Moral freedom is the fundamental characteristic of the moral discipline in the college stage of development. The young man has come to the time when he must govern himself, when he must make his own choices though right choice be ever so hard, when he must face public opinion and stand for his own convictions, when he must meet real temptations with a man's judgment. Of course the college faculty must do something to facilitate the transition from home to independence; they must see that the young boy is not overwhelmed by too sudden and too difficult forcing of moral issues. It is not fair to him to put him into a room with a gambler as his chum, or to locate him in the midst of a group whose room is a center of intemperance, or to send him to the city with a set of older men who are already rotten with immorality. The Faculty must try to give the boy a fair chance to fight his moral battles; they must try to give him as fair a field as you and I have with the restraints of family and profession and society about us ; sometimes we fail to do that, and the immature boy has to meet situations more difficult than we men have to face. That is not fair to him. But at the most the restraints and protection can and ought to go only a certain distance; freedom is the essential for his new stage of development. In such a situation what is to be his great safeguard? Unquestionably, public sentiment. Will your boy leave college a shifty, shrewd fellow, whose word is good only so long as he is in sight? Will he leave with a habit about his neck that will land him where we have seen some of our own college friends in their pitiable failure? Will he be unfit to marry your classmate's daughter? Will he join the great army of self-seekers? That, gentlemen, depends not chiefly on the faculty of the college, not altogether on the good home that you have given him, not much on what lie knows or does not know about good and evil—it depends, very largely, almost altogether, on what sort of a moral atmosphere he finds in your alma mater. And that is something that cannot be purchased with your money, or built by all your contributions combined: the moral atmosphere of the college; the product of tradition, of thought and life of the faculty, of student reaction one upon another, of alumni influence. There is no one thing that the alumni as a body so long for—for most of the alumni are fathers. Can this council help the alumni create a fine moral sentiment among the undergraduates?

It seems to me that the council might well take an early opportunity to investigate and discuss moral conditions and sentiment in the College. The need of a better sentiment as regards common honesty has long been felt. The traditions of the New England colleges in this regard are not of the best. We may well envy the University of Virginia her fine traditions of the honor that belongs to the gentleman and the scholar. We need to cultivate a sentiment for simple, every-day honesty. The real difficulty in the fraternity situation all goes back to the fact that the members of one fraternity do not believe they can trust the promise of the members of another. No ingenious system of pledging-dates and fraternity councils will amount to much while that belief prevails. The remedy must go to the heart of the difficulty. The alumni can do more than any other body to develop a sound undergraduate sentiment for common honesty. The students have the most profound respect for alumni opinion, if they become convinced that the alumni demand that the Dartmouth man be an honest man, they too will demand it.

So of intemperance. We all recognize it as one of the great perils of the life of young men. But the faculty could not attempt to enforce total abstinence, if they. would. Family custom and public opinion everywhere are too much divided as to the matter itself, and any attempt to enforce so personal a thing would plunge us into absurdities. Who will define just what percentage of alcohol is to make a drink forbidden? How many glasses may a man drink without being subject to college discipline? Moreover, the attempt to enforce so personal a thing, even if it were practicable, would run counter to the fundamental principle of personal freedom as a necessary factor in moral education. The faculty can only attempt to repress and punish gross disorderly conduct; but that amount of suppression offers very little protection to your boy who comes from home into the freedom of dormitory life. His only real protection has to lie in the sentiment of dormitory or fraternity house. How are the alumni influencing that sentiment? They touch undergraduate life most closely on occasion of class reunions at Commencement. It is a most serious • question whether faculty and student influence can counteract the annual testimony given by the younger returning classes that intemperance is a necessary accompaniment of college fellowship. Faculty discipline enforced upon undergraduates becomes impotent if it is in flat opposition to alumni practice. Cannot the alumni recover the situation for the sake of their own sons?

My thought of the relation of the alumni to the College keeps coming back to the power of the alumni to create college sentiment. I do not forget the financial opportunities. I expect to see great results of the leadership of this council in strengthening the financial support of the College. But I put no whit behind the financial opportunities and responsibilities the possibility of the creation of a compelling college sentiment for the intellectual life and the clean life. The college boy is peculiarly subject to public sentiment. We as fathers and faculty give him his freedom as being necessary to his moral development, and the first use that he makes of it is to enroll himself as the loyal subject of public opinion. What the other men are wearing and saying and singing are law to him. There is no time in a man's life when he is quite so sensitive to the opinion of the men about him as in the four years of college life. We must recognize the fact, and take advantage of it, for it has great possibilities for the development of high ideals. The sentiment of the Dartmouth alumni is sound and good. If this council can bring it to full consciousness and then bring it to bear on undergraduate sentiment, we can do' a fine and lasting service to the Old College.

PRESIDENT EMERITUS TUCKER

The letter which Doctor Tucker had addressed to the Council was read by Air. Hopkins. 'lt was as follows, in full:

The natural approach to any present discussion of this question is through the history of what is now known as the "Alumni Movement". Approaching the question in this way we can best see just what part of their function the alumni have already assumed, and also what remains to be carried out in proper adjustment to existing conditions. Evidently the relation of the Alumni Council to the Board of Trustees, both being representative bodies, requires careful adjustment.

For a century the College was under the management of a close corporation. This management was accepted without much questioning. At different times, especially in 1830 and again in 1845, the interest of the alumni found very practical expression in substantial gifts. In later periods the attempt to raise money from the alumni called out more or less discussion in regard to alumni representation. There was no considerable gift from the alumni as a body after 1845 until alumni representation had been accepted: and yet I ought to say, as a matter of experience, that the generous gifts of the alumni were not started by the accomplished fact of alumni representation so much as by the sentiment created by the burning of Dartmouth Hall. Alumni representation on the Board of Trustees in the way called for was brought about in 1891. Subscriptions from the alumni toward such a specific object as Webster Hall came in very slowly until after the call issued at the time of the burning of Dartmouth Hall, February 18, 1904. Since that time the alumni have given Dartmouth Hall, Webster Hall, the Gymnasium, and various sums for other specific purposes, through general subscription.

At the Centennial of the College in 1869, Dr. Bartlett, then of Chicago, afterward President, introduced a resolution calling for a "closer relationship between the College and its great and powerful body of graduates". Another resolution offered by Judge Barrett immediately followed, calling for the appointment of a committee of ten "to have in charge the whole matter of raising a fund of $200,000 and of coming to a suitable understanding with the Board in reference to the representation of the alumni upon it". Nothing came of these resolutions either in the way of money or of representation, except the appointment as Trustees of two men of this Committee, Dr. A. H. Quint and Honorable George W. Burleigh, to fill vacancies then existing. In 1875 the agitation was renewed by a resolution of the New York Association presented directly to the Trustees calling for alumni suffrage. After full debate in the Board a motion favoring the principle was adopted by the casting vote of President Smith. The plan which the Trustees then adopted and proposed to the alumni at their next annual meeting in 1876 provided that the next three vacancies on the Board should be filled on the nomination of the alumni. Each alumnus was to vote for four candidates for each vacancy. From the four receiving the highest number of votes the Trustees agreed that "ordinarily and in all probability invariably they would elect some one to the vacant place". This plan was accepted and carried out, and the Trustees, exercising their judgment in respect to the four highest candidates voted for, chose Governor B. F. Prescott for the first New Hampshire Trustee, Hiram Hitchcock:, a resident of Hanover, for the second, and myself, then of New York, for the vacancy outside of New Hampshire.

Though a distinct advance toward alumni representation was made by this action, it failed of reaching the object which was uppermost in the minds of the alumni, viz., such a mode of representation as should result in "an annually recurring obligation" on their part in filling places on the governing. board. The election of a trustee for life, although nominated by the alumni, precluded the exercise of any "annually recurring obligation". As discussion continued the difficulty of securing this object became more apparent, owing to the terms of the charter which implied the election of a trustee for life. The proposal was made that an advisory council of fifteen be elected by the alumni to cooperate with the trustees, but this proposal, though urged by several prominent alumni, found little acceptance with the general body. When the discussion next reached the stage of definite and urgent action—from 1888 to 1891;—two plans divided the support of the alumni: first, the plan to amend the charter by increasing the number of trustees from twelve to seventeen, the five added trustees to be elected directly by the alumni according to a definite scheme of rotation; and second, the plan to admit three by a like scheme of rotation within the board, without enlarging its number. The objection to the first plan was that it required an amendment to the charter. The objection to the second plan was that it seemed to evade the provisions of the charter in respect to life membership. The plan finally agreed upon was a modification of the second, allowing, however, five instead of three to have place within the Board as constituted by the charter, the legality of the method having been affirmed by high legal authority. This plan went into operation in 1891, Dr. C. P. Frost of Hanover, Judge James B. Richardson of Boston, and Mr. Charles W. Spaulding of Chicago taking their seats on the Board in October of that year, and Rev. Cyrus Richardson of Nashua and Frank S. Streeter, Esq., of Concord in the following year, 1892.

I have dwelt at considerable length upon the movement for alumni representation upon the Board of Trustees, partly to show the earnestness and persistence of the alumni in this matter, but chiefly to emphasize the fact, for its bearing upon present conditions, that much more was actually achieved than was originally proposed or even intended. Instead of five trustees to be elected by the alumni in addition to the original board of' life members (giving but five out of seventeen), according to one plan proposed; or instead of three to be given place within the original board, according to the other plan proposed, the final result was five members within the board, making one-half of its membership apart from the President, and the Governor ex-officio, direct representatives of the alumni—a much larger proportion than then existed or now exists in any other New England college. The close corporation was thus virtually supplanted by a governing board "in the hands of the alumni. The alumni, that is, actually assumed the function of government. In the first place, the contention of the alumni was for a part in the government of the College, not for some advisory relation to the governing board. In the second place, the proportion of alumni representation gave the alumni the influential control of the board. It is quite inconceivable that so far as the general policy of the College is concerned or so far as any disputed questions may arise, the five direct representatives of the alumni would not be more influential than the five life members, if the two parts of the board should be at variance. And in the third place, the method through which alumni representation was made to apply to five members might be extended, without any violation of principle, to apply to the ten members. Indeed this plan of making all the memebers of the board, except the President and the Governor ex-officio, an elective body, serving for a limited period, found some very strong, advocates at the beginning of the agitation for alumni representation.

I cannot refrain from repeating the statement that Dartmouth occupies a unique position among the New England colleges in regard to its governing body. Harvard retains the close corporation, supplemented by another board with secondary powers. Yale with a single board retains the close corporation in practice through the proportion of life members elected by the board to those elected by the alumni, twelve to five. Dartmouth retaining the single board, has virtually given it Over, as has been seen, to the control of the alumni.

The bearing of this fact is evident when we turn to consider the use to be made of the Alumni Council. There seems to be no need of any further assumption of the function of government. The Board of Trustees as at present constituted suffices for all purposes of government, or if at any time it should appear insufficient, the way is still open for further alumni representation within the governing board. I see no reason, therefore, why the Alumni Council should become a second board of control with minor powers. On the other hand, there is great need of some agency which shall support in substantial and effective ways the purposes and plans of the College as expressed through its administrative board.

It must be remembered that the close corporation which has now been supplanted was not without certain advantages. It derived advantage from the continuity of its membership. It derived advantage also from freedom and range in the choice of its members. It was possible to bring into the Board of Trustees men broadly representative in the affairs of Church and State, and thus to conserve and utilize interests which might be outside those of the alumni, yet associated with the origin and traditions of the College. The loss of these advantages must be counterbalanced by the organized support of the alumni. The alumni having assumed the function of government must bear its responsibilities. And these responsibilities must be the full equivalent of those originally borne by the close corporation in the endowed colleges, or by the State in state universities.

If I understand clearly the object of the formation of the Alumni Council, it is, in part, at least, to point out and make effectual the various ways in which the alumni can justify their assumption of the government and administration of the College. Much can be accomplished as indicated in Art. 2, Sec. 1 of the Constitution, by removing all friction and waste in efforts which may be made and by correlating these efforts with a view to their greatest efficiency. But I am inclined to think that the chief stress must be laid upon the last specification, viz., to "initiate and carry on such undertakings or to provide for their being carried on as are reasonably within the province of alumni activity". I believe that a.great deal of thought and time will have to be expended in initiating and carrying on undertakings of moment to the College.

To be specific, I.—In regard to undertakings involving financial support. Here I think a great deal can be accomplished in two ways, First,'—by impressing upon the alumni the fact that the College must depend upon them increasingly for financial support. I an- ticipate a relative decline in the gifts of men of wealth to our colleges and universities who are not personally interested in them. Other objects which invite their beneficence are steadily coming to the front. It is no more than right that as the alumni of our colleges increase in wealth, the colleges should share in the increase. But the necessity for this should be made apparent. It should be made apparent, that is, that access to outlying wealth is growing 'more and more difficult, because of the incoming of new and large public demands upon private beneficence. The individual alumnus, if a man of wealth, needs to feel more than in the past the spur of a common loyalty, as well as the influence from the example of some great giver, like Edward Tuck.

Second.— by furnishing to the College through the collective effort of the alumni, a constant and reliable but flexible fund for current uses. Harvard accomplishes this through the use of the class organization, each class on its 25th anniversary being expected to be prepared with a gift of $100,000 for this purpose. The Yale method, with which you are familiar, makes use of the class organization to a degree, but distributes the burden as fully as possible, so that the administration may count on annually dependable gifts. Such a fund is becoming an absolute necessity to any college. No budget can prevent a deficit, or perhaps better, there are times when a budget ought not to prevent a deficit. A deficit may be an unmistakable and assuring sign of vitality and growth. The essential thing is to make such provision for it, through a current fund, as may enable the College to meet the various exigencies of progress. In illustration let me quote from the Yale Treasurer's report for 1913-13, which has just come to hand, pp. 21 and 22: "How dependent the University is upon the yearly gathering and uniting of the gifts, small and large, of the graduates through the Alumni Fund Association, has been a matter of common knowledge to many, but unfortunately not to the majority of Yale men, for some years. Those who have failed to appreciate the importance of the Association's work will do well to ponder the situation in which the University would this year have been placed without the gift to General Income by the Association of $65,000; or even the less embarrassing, but still distinctly uncomfortable position of University finances, had not they been benefited by an increase of $15,000 in the amount of the gift ,over the $50,000 the Associatiation has been practically able, in so far as the University budget is concerned, to guarantee annually. Since its organization twenty-three years ago, the Alumni Fund Association has given to the University for use as income $502,943.84, in addition to which it has built up the Fund itself of $659,157.49; so that its total gifts have amounted to $1,161,201.33."

I see no reason why within ten years Dartmouth may not be in receipt of an annual fund from the alumni of at least $25,000, which in subsequent years may attain to very large proportions, proportions which may now seem to be purely speculative. If the Alumni Council can organize and maintain the support of the alumni through such a fund, it will act quite as much in the way of stimulus as in the way of relief. How the fund should be managed and adminisistered, whether by the Council as an incorporated body or by the Trustees, is altogether a matter of agreement. Probably much light might be thrown upon this question by inquiry into the experience of the universities referred to.

II.—In regard to efforts to maintain the supply of students. Here I think effort should be made to regulate as well as maintain the supply. The prevailing reasons which attract students to an older college are its history, the recognized character and position of its graduates, and its. educational equipment and standards. Among the immediate and active causes may be reckoned the influence of its alumni. This is especially noticeable in a college like Dartmouth, whose graduates are scattered so widely over the country. I think that the continued effort of 'the alumni in this direction may be counted upon. It is perhaps the most direct and effective way in which the loyalty of the alumni has thus far found expression.

I think, however, that the time has come to consider the best means of establishing and regulating this general source of supply. " And the method which seems to me most efficacious is that of putting the College into definite and permanent relations to some of the better secondary schools throughout the country; especially to those which are identified with the public school system. The stronger colleges have always made this kind of an investment in a constituency. Many of the old academies were direct feeders of the different colleges. The same persons were interested in certain academies and a given college. More recently, private schools have been established in the interest of a college or university. The suggestion has been made from time to time that one or more of these schools should be established as feeders for Dartmouth. Possibly the experiment might be of value. I have in mind one or two men who would make admirable headmasters of such schools. But for the most part it seems to me better for the alumni to avail themselves of the advantages already existing in connection with the high schools of the country. Instead of raising an endowment for a private school, why not endow 'substantial scholarships in high schools with which it may be desirable to establish permanent relations? If Dartmouth is to maintain a national constituency, it must localize its constituency. Why not make Cleveland, Detroit, Omaha, Denver, and like centers permanent sources of supply? If five or six scholarships were established at each of such centers, giving sufficient income to cover tuition, at least, they would secure a steady supply of first-class and therefore influential students. Each man so provided for would bring others with him and in time the College would come to have a recognized place in the life of the community. But to reach this result it would be absolutely necessary to make an outright endowment of a given school or of the local board of education for this purpose. A scholarship or a system 'of scholarships, which might be withdrawn at pleasure, would produce little impression on a school or community. An outright endowment would give the unmistakable impression that Dartmouth was proposing to make a home for itself .in that locality.

Of course such an identification of the College with the public school system of the country would have to be carefully considered as a matter of educational policy. But if accepted "and endorsed it would give the alumni in different sections and as a whole, the opportunity to make a large and sure investment in behalf of the College. This investment in a constituency seems to me to be in accordance with the policy of various colleges toward private fitting schools and academies. It would serve to regulate the supply of students both in quantity and quality. It would be much more economical, even if carried out quite extensively, than any attempt to accomplish the same end through the establisment of special fitting schools. The moral effect would be far better. More variety and more virility would be given to the undergraduate body; and, possibly of still greater importance, direction might be given to the preparation of some of the students looking toward Dartmouth. For example, at the present time if it should be thought desirable by the Administration, in the interest of scholarship, to secure a certain proportion of students fitted in Latin, the object might be reached through conditions attached to a part of the scholarships.

III.—Respecting the function of the Alumni Council in serving as a "clearing house for alumni sentiment" or as a court for the approval or disapproval of alumni projects, I have but a single suggestion to make. Unintelligent criticisms may for the most part be avoided and sporadic plans anticipated by ready information furnished by the Council or by definite and comprehensive plans devised and put into operation. The greater the initiative of the Council the less need there will be of repressing criticism or of harmonizing activities. I think that the success of the Council will depend very largely upon the ability and the willingness of its members to familiarize themselves with the current work of the College .and with the plans of the Administration. Very naturally alumni members of the Board of Trustees will be chosen in part from members of the Council. At least the Council in so far as it can prove itself efficient may be expected to be a training school for official service. Whether or not this result follows, it goes without saying that the value of the Council will depend upon the thoroughness of its information about college affairs, enlarged by its study of educational methods as seen in operation in different parts of the country. I do not anticipate that what may be termed the intermediary function of the Council will often be called into use. But should occasion arise, the necessary knowledge should come not from a special investigation, but from previous acquaintance with the essential facts. The Council can thus render most valuable support, where it cannot properly take the initiative, as in respect to the educational policy of the College. Probably few of the graduates of the College understand the full meaning or the full effect of the persistent development of Dartmouth as a college, in the midst of the educational experimentation which is now going on. The members of the Council, and the Council as 'a body, ought to have a ready answer to the question: "Why does not Dartmouth do this or that?" in the definite and clear explanation of just what Dartmouth is doing and why it is doing its present work. The alumni of the College should be apprised of the significance of all changes and advances in the working out of the College ideal. There may be occasions when this and like information can best come through the Alumni Council.

IV.—There is a fourth service which calls for a reminder only, it is so distinctly an alumni duty and is so obvious, viz., the gathering up of all memorabilia of deceased alumni, which might otherwise be lost. The efficient work of the class secretaries will provide for the more recent classes. Something has been done in reference to alumni who were associated with critical periods in the history of the College. What is needed is a careful and comprehensive investigation of the career and public service of the graduates of the last century. Chapman's History of the Alumni ought to be revised and brought down to times of present activity. This is an appropriate task for the Alumni Council, rather than the Trustees; also the securing of portraits or other memorials of the more distinguished graduates. In like manner local associations now' have the opportunity to gather up and preserve the records pertaining to Dartmouth pioneers in this and in other countries. I used to speak of this most attractive duty when visiting alumni associations. But lam quite sure that it will never be taken up except through concerted action. The field is large and as I have said attractive; perhaps richest where the association may be small, as in Cincinnati, Indianapolis, or Detroit, in the far West, and California. The time will come when these records will be inaccessible, and not only the College but the country will suffer loss. The same thing is true of the foreign missionary service .in which many graduates of Dartmouth have taken a prominent part, whose sacrifices and deeds may now be properly established, as missions have risen to such international importance. Of course the field of special investigation is Washington. The Government from its foundation has never been without representatives from Dartmouth in various departments. In the national Congress there have usually been one or more representatives serving at the same time in each branch. What Commissioner Harris termed the "directive power" of Dartmouth may easily be traced in the history of national" legislation.

They seem to need an organization which shall aid in carrying out some of the responsibilities and obligations taken up, perhaps unwittingly, with the function of government—an organization which shall also help to make college sentiment steadily and practically efficient. I look with confidence upon the Alumni Council as the instrumentality best fitted to secure this two-fold result.

MR. CAMPBELL

Richard C. Campbell '86 of Denver spoke for the alumni; though he denied responsibility for any except his immediate group. He had his hearers with him, however, when he arraigned the flabby intellects of present-day youth, and attributed the condition to present day easy-going methods of education from the primary grades through the average college course.

Mr. Campbell emphasized the country's need of men who can think accurately, perform thoroughly, and who have a developed sense of responsibility. Such men, said he, are being sought, for the most part with poor success, by the business and professional world. He likened the college to a manufacturing plant, which, in turning out a product, should seek to satisfy a specific demand for high quality. For his own part, he believed that Dartmouth should have a program of accomplishment whereby its diplomas would come to be generally accepted as a guarantee of utility.

The carrying out of such a program, he stated, would involve heavy capital investment; not less than $5,000,000 at the outset. But he felt sure that, if Dartmouth could go before the country with guarantees that it was in a position to make really effective use of a sum, it would be forthcoming. The aim of Dartmouth, in short, should be to give a disciplinary education of strictly undergraduate grade, in charge of the men best fitted to teach, and open to every young man who could present the proper moral and intellectual qualifications.

Mr. Campbell summed it all up when, in closing, he declared: "I would have Dartmouth known not as the poor man's college, or as the rich man's college. Poverty or riches are no indication of either mind or soul. I would have Dartmouth known as the ambitious man's college. And once that reputation is clearly attained, you can not build a wall around the institution high enough to keep out the best youth of the land, nor will you lack for funds to accomplish the larger purposes that will constantly unfold."

SUMMARY BY MR. KEYES

Mr. Keyes, who had been assigned to summarizing the evening's discourse, followed Mr. Campbell. He paid-tribute to the latter's remarks, declaring them to constitute the most advanced and enlightened educational doctrine that he had encountered for a long time.

For the rest, Mr. Keyes confined himself to pointing out the salient features of the various addresses. At the end he laid stress upon a policy which be felt the Council should adopt in all its enterprises. Put in the form of a motto it was: Do not begin any enterprisewhich some one else must finish.

COMMITTEE APPOINTMENTS AND OTHER BUSINESS

The interest aroused by the series of talks set on foot a general discussion that indicated that the conference had been of large value. The tact of the presiding officer, however, directed the meeting to the consideration of further organization through the appointment of working committees. Shortly be- fore midnight it was agreed to leave the question of such committees to Messrs. Hopkins, Richardson, Livermore, Howland, and Blair for consideration and report on the morrow.

The five men thus named sat up over their task until three in the morning. But they did their work well. At nine o'clock their recommendation was presented and accepted. Five committees of five men each were suggested; but as preliminary a special resolution was presented.

Mr. Mathewson's statement on matters financial had precipitated discussion as to the scope of the Tucker Alumni Fund and had made fairly clear the need of establishing an alumni fund upon a somewhat broader basis than had usually been accepted for the Tucker fund.

In order to clear the way in this matter and ensure proper adjustments with the Tucker fund projects, the committee presented and the Council passed the following:

Voted: That the Alumni Council place itself on record as favoring the establishment of an alumni fund; and that a committee be appointed to arrange details of organizing for the establishment of such a fund in harmony with movements already in progress; and that this committee "report to the Council at its next meeting.

This being accepted, the way was paved for. appointing the committees, which was done as follows:

On alumni relationship to undergraduate affairs: J. R. McLane '07, Chairman, H. P. Blair '89, P. G. Redington '00, H. E. Keyes '00, E. M. Hopkins '01.

On alumni relation to preparatoryschools: A. L. Livermore '88, Chairman, W. Thayer '80, C. W. Pollard '95, W. McCornack '97, S. C. Smith '97.On alumni projects: IT. G. Pender '97, Chairman, C. D. Adams '77, C. B. Little '81, R. C. Campbell '86, C. W. Tobin '10.

On publicity and budget: L. B. Little '82, W. G. Aborn '93, M. C. Tuttle '97, I. J. French '01, J. F. Drake '02.

On alumni fund: F. A. Howland '87, H. L. Moore '77, E. A. DeWitt '82, W. T. Abbott '90, J. P. Richardson '99.

It was then voted that the president of the Council be ex-officio member of all committees.

MR. T'UTTLE AND A SECRETARYSHIP

Mr. Tuttle was now called upon to express his ideas regarding the creation of a new officer, an alumni secretary, serving with pay. He pointed out that an essential of the efficient conduct of large alumni projects, was an officer whose first business would be that of seeing things through. Such a person must be paid for his services, since he must give all his time to them. His employment Mr. Tuttle believed would be justified by directly increased returns in dollars and cents for the benefit of the College.

The question had been before the alumni for some time past. It should now have thorough consideration with a view to disposing of it. He accordingly moved that a committee be appointed to report on the advisability of a paid alumni secretaryship, the probable cost and probable income of such an office, and, if its establishment is considered advisable, a complete plan for the same, together with recommendation as to a proper person to occupy the position of secretary.

The motion being carried the chair appointed Messrs. Tuttle, Abbott and Drake to wrestle with the problem presented.

Various letters were read suggesting a variety of occupations for the Council. Some of them produced discussion but eventually all of them were referred to the committee on projects.

Appreciation of the contributions of those invited to speak was voted and the secretary was directed to forward a telegram of greetings to Doctor Tucker.

The Bellevue - Stratford management came in for a word of thanks for courtesies and the meeting adjourned.

*For a statement of the facts relating to alumni representation given in clear perspective and in full detail see the forthcoming volume of the History of Dartmouth College' by Professor John K. Lord, pp. 378-381 and pp. 455-471.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTo all alumni this, the Alumni Council

December 1913 -

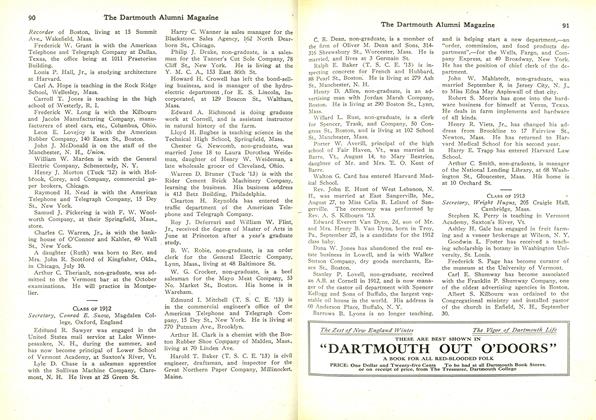

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1907

December 1913 By Richard S. Southgate -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

December 1913 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1912

December 1913 By Conrad E. Snow -

Class Notes

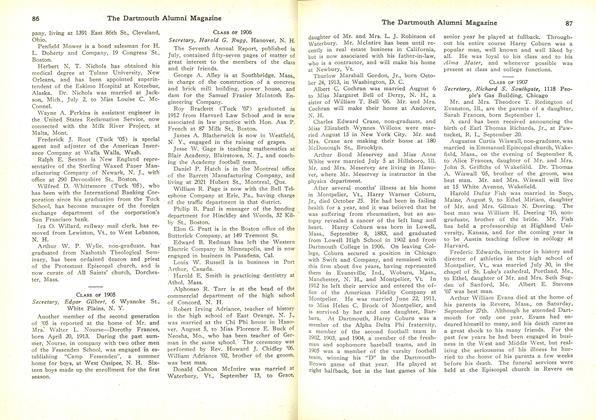

Class NotesCLASS OF 1906

December 1913 By Harold G. Rugg -

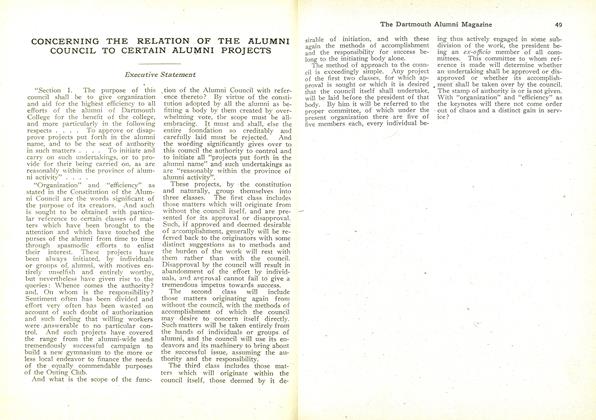

Article

ArticleCONCERNING THE RELATION OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL TO CERTAIN ALUMNI PROJECTS

December 1913