Henry C. Morrison '95, Superintendent of Public Instruction for NewHampshire

On the twentieth of February last in Manchester the writer delivered an address, entitled, "The New England College Situation." The address, which received a very considerable publicity in the newspaper press, was primarily intended to call to the public attention the conditions growing out of the existence of the New England College Entrance Certification Board, but it went further and expressed the belief that the development of the State College at Durham into a full state university would be the only ultimate solution of existing problems relating to higher education for the masses in New Hampshire.

The address did not in any way single out Dartmouth for attack, but it did of course include Dartmouth with the other fifteen colleges making up the membership of the New England Board. In view of the statements made at the time of the address in question, the editor of the Alumni Magazine asks me, as an alumnus of the college, to present the matter in the form of a magazine article so far as it relates to the need of a state university in New Hampshire. And this I am very glad to do.

First of all, what is meant by a state university? College men in the East, and especially in New England, have traditionally looked with impatience upon the assumption of the title "University" by an institution of collegiate grade, preferring that the term should be reserved to the use of institutions which emphasize graduate study as an important part of their mission and which are properly equipped to carry on such work. With that attitude the writer is in entire sympathy. But. nevertheless, during the past quarter century or more there has been evolved an institution of perfectly definite purpose west of the Alleghenies and known as a State University. Its function has come to be primarily the interpretation of all the common life of the people in educational terms, with or without graduate schools as a part of its equipment. It is controlled by the State and draws the major part of its support either from appropriations made by state legislatures or from the income of public invested funds. It helps materially to mold the best thought of the state and in turn, from the very conditions of its existence, is sensitive to popular, demands. It is frequently administered in accordance with a conception of the educative process quite different from that in vogue in the eastern endowed institutions. Whether such institutions have any right to the title "University" or not is beside the question. Whatever a university may be, we have an increasingly definite idea in mind when we use the term "State University": we mean an institution of collegiate grade, under public control, closely connected to the public school system, and intimately related to the common life of the people. Such an institution has been developed with great success in the State of Maine. L think that such an institution will be developed in this state and in each of the New England States unless the New England College situation shall be profoundly modified in time to relieve the pressure.

Viewing the situation as it stands today. New Hampshire needs an institution of collegiate grade under public control adapted to receive all graduates of her high schools without discrimination as to the nature of their high school work, and forbidden to erect any artificial obstacle between high school and college or to combine with other institutions to do so,'—for the following reasons: first, because the majority of the graduates of the public secondary schools of the state are now leaving the State for their higher education; second, because many hundreds of pupils in such secondary schools are now annually barred from higher education by unnecessary restrictions surrounding college entrance, and by the failure of higher institutions to adapt their curricula to existing public needs; third, because the possession of a complete institutional life of its own is essential to the normal and natural development of the State; and fourth, because the State cannot safely leave in private hands the entire guidance and development of its education.

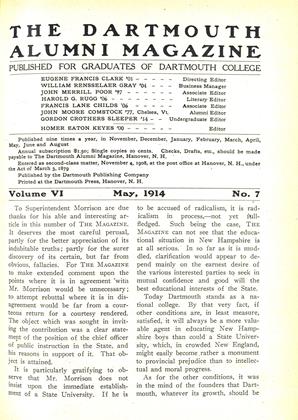

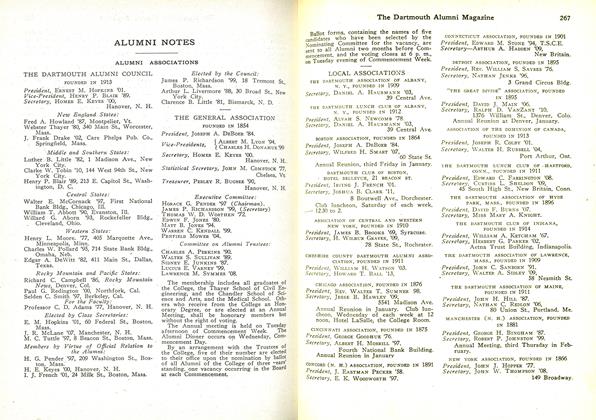

The following table will show in a general way the drift of graduates of New Hampshire public secondary schools for the past eight years and to some extent for the past twenty years. Column I shows successive Dartmouth classes. Column II shows the catalogue enumeration of each class in its freshman year in college. Column III shows the number of New Hampshire students in each freshman class. Column IV shows the number of graduates of New Hampshire public secondary schools who entered some college with the corresponding Dartmouth freshman class. The first records available for the secondary school class are for the academic year 1905-06. This column includes all secondary schools in the state, excepting Phillips Exeter Academy, St. Paul's School, and the Brewster Free Academy.

TABLE I I II III IV CLASS TOTAL FROM N. H. Students entering some college from N. H. Schools 1897 120 40 1898 103 28 1899 132 48 1900 161 56 1901 179 45 1902 187 52 1903 184 39 1904 201 55 1905 215 63 1906 230 59 1907 291 82 1908 255 56 1909 303 63 1910 355 50 165 1911 357 56 191 1912 334 58 194 1913 309 57 236 1914 398 57 222 1915 425 56 224 1916 405 58 255 1917 382 50 245

The figures in the above table are subject to certain corrections. In columns II and III would appear not only the college freshmen for that year, but also men from preceding years who had been dropped a year or more. In column IV are included not only secondary graduates for the corresponding year, but also a few who had graduated the previous year and deferred entering college. And of course column IV contains women as well as men.

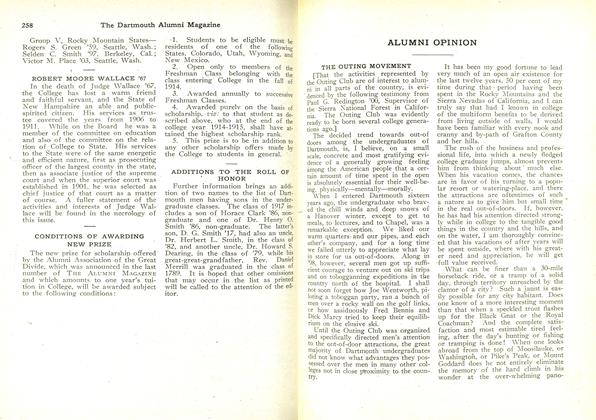

Table No. II shows the exact distri- bution of the secondary school class of 1913. The figures are derived from a special inquiry addressed to the several principals.

TABLE II

Total number graduates 1913 who entered college in the fall of 1913—240. These were distributed as follows:

Dartmouth 30 N. H. State 64 (men 43, women 21) Norwich, Vt. 16 Simmons College 12 Middlebury 12 (men 4, women 8) Boston University 9 (men 5, women 4) Bates 9 (men 4, women 5) Smith 8 Wesleyan 6 Brown 6 Mt. Holyoke 5 Trinity 5 Wellesley 4 30 other colleges 59

It would appear that of the 50 freshmen whose addresses are given as New Hampshire in the current catalogue of Dartmouth, only 30 were graduated from New Hampshire public secondary schools with the corresponding class. The others must be either (a) students repeating freshman work, or (b) students prepared at Exeter, St. Paul's School, or Brewster, or (c) students giving a New Hampshire address who were prepared elsewhere than in New Hampshire.

Hence, of 245 students graduating from New Hampshire public secondary schools in June, 1913, 101 entered New Hampshire colleges, including 7 at St. Anselm's, Manchester, while 144 left the State. Most of these will probably permanently reside elsewhere. Such a drain of the potential leadership of the next generation is a loss which no State can contemplate with equanimity. Of the whole number, 168 were young men and of these less than 18% entered Dartmouth.

In addition to the 245 enumerated above, about 50 left the State to pursue studies of such special types as music and other forms of art, commerce and the like, which might easily and properly be made component parts of the program of a state university.

Many hundred pupils now in high schools are barred from college either by unnecessary restrictions surrounding college entrance requirements or by failure of the colleges to adjust themselves to modern needs.

The enrollment in New Hampshire public secondary schools has about doubled in the past ten years and the state has now a larger proportionate number of pupils in this class of schools than has any other state in the United States. The enrollment will probably steadily grow for some years to come. The rate of increase during the past decade has outstripped population nearly twenty to one. This is due partly to the establishment of new high schools, but chiefly to the increased enrollment of existing high schools. The percentage of this enrollment which is definitely preparing for college is about 20%, although of course not all who prepare for college finally realize their ambitions. But practically the entire enrollment is doing work of a grade which qualifies for higher work along the same Or kindred lines, and if there were in existence a college or state university which would take this work and carry it on, it is probably not too much to say that 250 boys and girls more than is now the case, annually, would present themselves for the advantages of the whole or a part of the college course.

So far as the possible higher education of the eighty percent or more whose way is now practically barred is concerned, the heaviest indictment lies against college entrance requirements or rather against the method of administering such requirements.

In the first place, the entrance requirements themselves are highly artificial and formalistic, and per consequence unrelated to the felt educational needs of the majority of pupils or then parents. A college faculty, or group of delegates- from several faculties, meets and determines a priori, by majority vote, what subjects ought to form the entrance requirements and how much of each subject, and further in what manner in general, each subject shall be taught,—the same method in general followed by Congress in drafting tariff legislation, with much the same give and take of personal interests and prejudices. The teachers in our secondary schools have no vote, but as for that matter the method would still be as mechanical and formalistic if they did have such vote. A world of debate has been devoted to the subject and numberless modifications in the requirements made, but with little essential relief, because the subject matter of the curriculum has still been left the center of gravity instead of the pupil who is to be educated.

The natural result is the one which we find in practice, namely, pupils must begin as soon as they are in the secondary schools to prepare themselves to leap over an educational hurdle at the end of four years, and it matters little whether that hurdle is in the form of a college entrance examination or in the form of the marks attained during the first college semester. Such a scheme has very little appeal to the average high school pupil and still less to his parents. He is entering our secondary schools in ever increasing numbers, but he is following the course of study which most appeals to his interests, which comes to him with the most quickening intellectual appeal. In proportion as the high school ministers to his felt intellectual needs he remains in school and graduates,—and he looks for further education upon the same principles wherever he may find it, whether in New Hampshire or in lowa or in Florida. There are many stubborn facts in education, but the most stubborn of all is the nature of the adolescent boy and girl, and the public high school is bound to adapt its program and its methods to that nature so far as it can be understood.

I he possibility of higher education for the masses rests upon the. principle that the college shall definitely give up the whole matter of entrance requirements as now understood, accept pupils from reputable secondary schools in the same manner in which these accept pupils from the elementary schools, and adapt their programs to the intellectual needs of youth who live and will live in the 20th century.

Still more does a just complaint lie against the method of administering college entrance requirements. Dartmouth allows her relations with New Hampshire public secondary schools to be settled by vote of a body of sixteen representatives of New England colleges upon which board she has but one vote. A girl from a given high school may totally fail at Smith and a boy at Amherst, while many others do creditable work at Dartmouth and elsewhere. No matter, the doors of Dartmouth are closed against that school and its graduates, except upon examination. Now it is very, very far from good logic to conclude that because a youth fails to do college work in his first half-year case lies against his high school for failure in preparation. He may, and frequently does, plunge madly into athletic diversions as soon as parental restraint is removed; she may, and frequently does, plunge madly into the college social whirl; both he and she may unfortunately meet with but indifferent instruction in the college classroom. In none of these cases does a just complaint lie against the high school, especially when many other graduates of the same school and the same class have done creditable work in the same college semester.

Scores of my readers are witnesses to the fact that by no means did the students who entered college years ago,' with the best preparation uniformly, do the most creditable college work throughout their college years. And the witness which you can bear is the witness which all we know of the science of education does bear.

The public school system must in the nature of things. serve primarily the common life about it. That is to say, high schools, especially, must provide that kind of education which will throw light upon the common experiences of mankind and give to them an educational interpretation. It must help its pupils to a rational understanding of their own bodies, of their own households, and of the fundamental vocations in which the work of the world is done. If possible, it must awaken in them an appreciation of the beautiful in nature and in art. It must develop in some of them at least a love for the world's best literature, both in the vernacular and in foreign tongues both ancient and modern. It certainly must inform them adequately of the character and meaning of American institutions. The science it teaches must be the science which helps to make life intelligible to the pupils under instruction, and not the science of the university laboratory. Its mathematics must be the kind of mathematics which enables the pupil to read the common affairs of life in mathematical terms, and not the abstruse manipulations which are for him merely mental gymnastics. Toward work of this type high schools in this state and other states are struggling as best they may. They will continue to do so for the pressure of a constantly growing student body drawn from, all walks of life so impels them whether they will or no. But at every point they are met by college professors who say, "Here, you can't teach this thing in that way. That is not physics, or history, or Latin, or mathematics, or English, as the case may be. There isn't any place in college for that sort of thing. You must stop it." So the school is practically driven to teach one kind of English or mathematics, or what not, for admission to college and another kind for those who are not going to college, or else to prepare nobody for college at all.

A specific case will illustrate. In 1903 the legislature of New Hampshire enacted that every secondary school in the state should give suitable and proper instruction in the constitutions of the United States and of New Hampshire, and it further decreed that the superintendent of public instruction should approve such work as having been done in accordance with the statute. Here was an eminently reasonable obligation laid upon the public schools of the state by the lawmaking power, and the law was enforced. But it was long before any college of the New England group would accept a year's work in United States history and civil government as being in any sense worthy of consideration as an entrance unit for admission to college, although ancient history and the civil government operated by archons, ephors, and consuls was still sweet and savory in the nostrils of committees on entrance requirements.

The possibility of higher education for the mass of our children involves not only the acceptance as valid entrance material of high school instruction of the type which I have described, but it also involves a complete modernization of the college program itself. Not only must the youth be allowed to present a capacity to read instead of linguistics; a set of reading characterizing him as an individual in the place of immature and premature literary analysis; a kind of physics, chemistry and "biology which really do teach him something of his daily life; a kind of mathematics of which he makes more or less habitual use outside of mathematics classes; an historical mindedness instead of a syllabus of historical facts; but he must also find opportunity m college to pursue studies of similar type, and further opportunity for that kind of intellectual growth. If it becomes necessary to postpone much of the existing college method to the graduate school where it belongs, so be it.

Now, the New England group of colleges as a class have on the whole steadfastly opposed any such adaotations. It is not for me to question the wisdom of their policy. It may be the correct policy for them to pursue. But if so, then I am clear that New Hamp shire should develop an institution of her own under public control to which all the qualified youth of the state shall have free access and which will prepare them to live efficiently and if possible happily under the conditions, of the 20th century.

People live together in these days in a highly complex society which organizes itself largely through various institutions. For the most part the sanctions under which we live in America are determined by the American State. That is to say, the sovereignty which touches us is chiefly the sovereignty of the state revealing itself in a multitude of governmental statutes and multiform activities. In such manner is charitable and correctional work carried on, professions are described and the entrance upon professional activity controlled, the interests of agriculture and commerce and industry are furthered, the public health and moral welfare are conserved and so on. Now, it follows, as it seems to the writer, that every state must essentially be a complete unit within itself so far as its institutional life is concerned. Its public acts, its legislation, its decrees, must be illuminated by its. own educational institutions and in turn it must possess its own institutions characteristic of its own life to give its life expression. The case of the Medical School will serve as a typical illustration.

Some years since a representative of the Carnegie Foundation gathered a great body of facts which seemed to indicate that we have in. this country too many practitioners of medicine and too many medical schools. The inference was drawn that the New England states would be sufficiently well served by two of the larger schools and that the others might well be abandoned. The State of Maine replied by moving the clinical years of the Bowdoin School to Portland, and the school continues in business. In this, I believe the state acted wisely, for it means that so far as medicine is concerned the state is still sufficient unto itself for the great body of its practitioners. I have no doubt that the Harvard Medical School with its great wealth of clinical material, with its ample facilities, with its generous support, can do a better grade of work than many, if not most smaller institutions. But I do not view with any complacency at all the crippling or the abandonment of our own medical school and our dependence upon Massachusetts for that part of our institutional life. I feel very sure that our remoter towns will still be served by others than Harvard graduates and I am very sure that they will not be the equals of the competent, hard-working, often heroic physicians and surgeons whom I know and who bear the Dartmouth degree.

But that is only typical. The state needs a great development of her institutional life, under her own control, and constantly growing into a closer relation to her own life. Let me confine myself to educational institutions.

First of all, we need a good undergraduate school of education. I don't mean a normal school. 'Our normal school policy is well developed and we shall carry it out, until we have put the entire teaching force in the elementary schools under training. But you cannot adequately train men and women to superintend schools or teach in secondary schools in the normal school; you need the prolonged training and broad education of four college years for that purpose. So far, Middlebury College is giving us about all the trained high school teachers we are getting, and of course that represents but a small supply. The Middle West has an immeasurably more adequate system of training teachers for high school and supervisory positions than New Hampshire, and in fact this state is very distinctly behind the rest of New England in this respect;

Then, we need an undergraduate commercial school of college grade. Had we such a school it would accomplish two things at once. First, it would open the doors of higher education to hundreds of high school pupils who now find them closed; and, second, it would make available for educational exploitation the immensely rich field of commerce. True, there is the Tuck School at Hanover, but this is a post-graduate technical school separated by three years of academic work from the high schools. No doubt there is room for post-graduate schools of this type and no doubt they will contribute in time very advantageously to the commercial life of the nation, but as an influence reacting upon and uplifting the commercial life of this state the Tuck School is, and will be negligible, for the simple reason that it cannot secure students enough for that purpose and can return very few graduates to the commercial activities of New Hampshire. The public insists upon commercial courses in the high schools. The public may be all wrong, but it will assuredly have its way since it contributes the money for the support of the high schools. Furthermore, these high school courses in commerce are yearly being made more worthy from the educational standpoint, viewing 'education as essentially an adjustment process. We need undergraduate collegiate courses in commerce, parallel with agricultural and mechanic arts courses in order to build upon the work which the high schools do. A whole chapter might be written on the possibility of laying here a broad intellectual foundation for post-graduate work in commerce, but I am already using too much space.

We need substantial four-year undergraduate work in the household arts. There is ample justification for a state university school of household arts based upon purely educational considerations, but I am interested here chiefly in the development of an institutional expression for the home life of the state. Of course Dartmouth could do nothing here, and the State College has already made a worthy beginning in this line.

I might continue and show how in a variety of ways the state needs the development of a rich institutional life of its own to broaden and conserve all its higher life and ultimately to make the higher life the common inheritance of all children born within the boundaries of the state. The instances which I have given will, I trust, make my meaning sufficiently clear.

Finally, the state cannot afford to have the character, the scope, the content, or the method of its education determined by private enterprise, by individuals who are in no sense responsible to the state nor to the people.

The public school system is .an instrument of government. Such has been the doctrine laid down in a multitude of decisions of courts of last resort both in this state and in other states. The power which controls the education given in the public schools today can determine the characteristics of society at a period within the lifetime of men who are already in middle life. It would not be difficult to show that the ferment which is now working in our national life is related to the great extension of compulsory education which occurred toward the beginning of the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and especially to the greatly increased enrollment which began to appear in the public high schools about 1880.

The power which controls the college under existing conditions can determine very largely what kind of education is to be given to the masses of American children whether they go to college or not.

It was never logical for the American state to allow such a state of things to arise. Few European governments tolerate it. But it has ever been the political genius of men who speak the English language to disregard the logic of a political situation so long as it works well in practice. Our habits in this respect have probably saved us from many violent revolutions, but they have also kept us busy protecting ourselves against the usurpations of non-governmental agencies. So here, nobody, seriously objects to the colleges, as strictly private institutions, exercising governmental functions even though such functions lie close to the dearest interests of the community, so long as the colleges in general are felt to be reasonable and to be working for the best interests of the masses of the people. I should fail in the main purpose for which I am asked to prepare this article if I omitted to say that the time has come when people in all walks of life, in this state and to my knowledge in all the four northern New England states, do deeply resent the control of our whole educational life by the colleges. Here, as elsewhere, the layman vaguely knows that something is wrong. The school people definitely know that the kernel of the matter is the combination of colleges known as the New England College Entrance Board. As a Dartmouth man it is painful for me to find Dartmouth men in charge of important public school interests definitely stating that they are using whatever influence they properly can to turn boys and girls to our State College and to other institutions not related to the Board. And not only is this true of Dartmouth men, but it is also true of teachers holding degrees from Harvard, Yale, Bowdoin, Bates, and Smith,—to mention only a few whose heated complaints I have, recently heard, and whose names I at the moment recall.

Here .is a growing pressure which I feel and realize, which I interpret as substantially a demand for liberty under the law in education, and which I am sure will find its appropriate vent. Maine has already settled the matter by the development of a state university. At several recent sessions of the Massachusetts legislature, bills have been introduced looking toward the erection of a state university. I have had informal proposals from at least one New Hampshire city to extend its high school so as to cover the substance of college work. I don't believe in that, but I know it could be done, if necessary. In a word, our people will have college education for the many and not merely for the exceptional few. If they can't get it in one way, they will in another. So long as the endowed colleges under private control will give the freest and broadest opportunity for all, the people will loyally support them and be glad to be relieved of the burden of duplication. But unless the pressure of college domination without public responsibility is removed, then either a state university or some other form of collegiate education under public control will take the place of existing colleges, just as the public high school took the place of the private academy half a century ago.

You ask me "What is Dartmouth's relation to this whole situation ?" I have to answer that Dartmouth's relation is exactly the same as that of the other colleges concerned. The situation would be just about the same if there were no Dartmouth College.

What, then, can Dartmouth do for education in and for the State of New Hampshire? In the first place, I think the Dartmouth faculty should sever all relations with the New England Entrance Board and deal with New Hampshire schools directly. I am sure that the present policy of allowing a board of sixteen men and women upon which Dartmouth casts but one vote, and fifteen of whom have no relation to New Hampshire whatever, to determine what Dartmouth's relation to the high schools of this State shall be, can be defended as neither wise nor worthy. The State intends that all its public secondary schools shall be reputable and strong institutions, and it provides competent inspection for that purpose, If the college is not satisfied with the inspection which the " state government gives, then let it inspect for itself. But once a school is inspected and approved, let its graduates enter college freely and let the college assume its share of the responsibility for their subsequent careers.

As to the immensely broader situation, I cannot speak with confidence. I do not pretend to know what the limitations of the college's present capacity to deal with the whole problem of the higher education of the many, if not the masses, may be. lam clear that we must have institutions in New England dealing with the whole college end of the educative process in a modern way and in response to modern popular needs, but whether Dartmouth ought to modify its program to meet these needs I cannot profess to be sufficiently informed to venture an opinion. That is a question for the college administration to settle, and I have every confidence that it will be settled wisely.

I have long foreseen that our whole American system of higher education is destined to pass through an evolutionary process of which the replacement of the old academies by public high schools was a type. So far as the colleges are concerned, it is to be regretted because it involves extensive duplication and waste. If the colleges find it possible to adapt themselves to existing needs, I think the process will abort, or at least that its accomplishment will be indefinitely deferred. Otherwise, I look to see somewhat the following changes take place within the next twenty-five years or some such period. Large and strong institutions, probably of the state university type, will be developed in the East as they have been in the West Most of the smaller endowed colleges will either be given up or will in some way be merged with the state or other institutions. The larger existing colleges of the Dartmouth and Brown and Princeton type will become essentially class institutions, attended chiefly by the sons of wealthy alumni and others who select that form of introduction for their sons to the social and business worlds in which they are destined to live. Such institutions would still serve a valuable and useful purpose in our national life and it may be that such an outcome will be best. As a Dartmouth man, imbued strongly with the traditions for which I have always felt that Dartmouth stood, believing that Dartmouth's glory in the past has been derived chiefly from the crude boys who came to her from our New England hills and villages and went out to be masters of men in many fields, I do not contemplate any such possible destiny for her with any enthusiasm at all. But, the old order changeth, a college lives on generation after generation, and none of us has a right to ask that the unfolding life of the college shall pause at the stage in which we happened to be of the body of its alumni.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTo Superintendent Morrison are due thanks for his able and interesting

May 1914 -

Article

Article"A BISHOP AMONG HIS FLOCK"

May 1914 By Ethelbert Talbot '70, L. S. H. '70. -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

May 1914 -

Article

ArticleTHE OUTING MOVEMENT

May 1914 By PAUL G. REDINGTON '00 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1912

May 1914 By Conrad E. Snow -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1876

May 1914

Article

-

Article

ArticlePROPOSED CHANGES IN THE CONSTITUTIONS OF THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION AND THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

May, 1922 -

Article

ArticleDean Bill to Retire June 30

June 1947 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for –

November 1968 -

Article

ArticleTrustee nomination: a reminder

OCTOBER 1984 -

Article

ArticleNo-Fault Insurance

APRIL 1994 -

Article

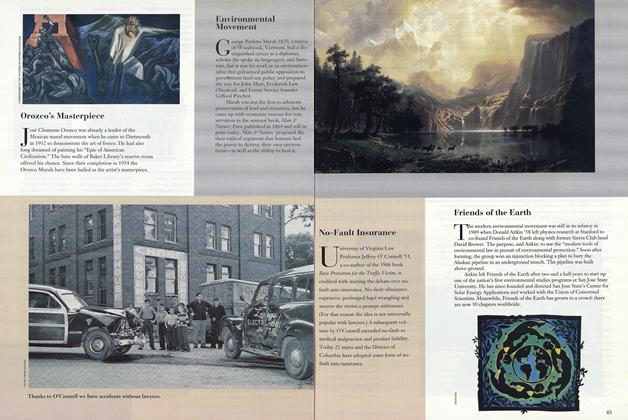

ArticleJUNE MEETINGS OF THE TRUSTEES

August 1917 By Henry Hoyt Hilton."