At a special meeting of the Trustees held in Concord, New Hampshire, June 13, Ernest Martin Hopkins of the Class of' 1901 was unanimously elected President of the College to succeed Ernest Fox Nichols, whose resignation became effective June 30. Mr. Hopkins entered upon his duties July 1. His inauguration will take | place probably October 6. Of that event due notice will be given to the alumni through the mails.

To those who have been closely in touch with Dartmouth affairs during the past fifteen years the choice of a President has brought little surprise. The wonder is not at the election but at its acceptance. The training which Mr. Hopkins has undergone since his graduation has been such as quite ideally to fit him for his new task. The rewards and opportunities, however, which in the past six years have been a part of his experience might naturally have tempted him to apply his talents as an educator to other than academic fields.

For Mr. Hopkins is, and has been, for some years past, primarily an educator. His sphere of operation has chanced to be the business world, where theory has been under the necessity of producing utilizable results in practice. He went Into business carrying with him an academic point of view that has constituted a very real factor of his success. He brings now to the College a business point of view that should be no less valuable in the academic environment. For one thing, it will help to differentiate him where differentiation will carry the weight of authority.

THE PRESIDENT'S CAREER

As has been said, Mr. Hopkins was graduated from Dartmouth in the Class of 1901. That fact in itself indicates that he is a young man. He is, indeed, not yet forty years of age, having been born in 1876 in Dunbarton, New Hampshire, eldest son of a Baptist minister.

His preparation for college was obtained at Worcester Academy. Having graduated from that institution he began his career as an educator by teaching school for a year. The next year, he entered Dartmouth. It would have been difficult to find anyone more thoroughly representative of the best qualities of the Dartmouth student of his time. The family traditions back of him were of the best; yet the necessity for earning his way through College was upon him. He knew no idle time in the college year or during the vacation period. In his studies he maintained high place; he was a prize winner in English composition. A variety of student interests claimed his attention and he. attained leadership in all. Following his graduation from College, Mr. Hopkins was appointed by President Tucker to be his secretary. At that time Dartmouth was fully entered upon its period of expansion. The burden upon President Tucker, which had become an overwhelming one, it was Mr. Hopkins' rare privilege, in unusual measures, to share. In five years he was made Secretary to the College, a position which he held until 1910, when he resigned to accept an outside offer.

During his nine years of service to Dartmouth Mr. Hopkins exhibited executive abilities of a high order. Serving for a time as graduate manager of athletics, he did much to win adequate recognition for Dartmouth among other institutions. The present increased effectiveness of alumni organization among Dartmouth graduates is due primarily to his initiative and organizing ability. The Association of Class Secretaries and the Alumni Council are both traceable to his effort. He was the founder and for long the only editor of THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE. He was, further, in close touch with President Tucker's educational policies and from that great leader drew inspiration that has notably affected his subsequent development.

His alumni activities did not end with the severance of official relation with the College. He was the first president of the Alumni Council, serving for two terms, and was an influential participant at various times in the affairs of alumni associations in Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. At the present time he is a vice-president of the Boston association.

PRIMARILY AN EDUCATOR

In 1910, Mr. Hopkins received an offer from the Western Electric Company to enter its service in charge of the recently established educational department of that corporation. At that time the corporation school was in its infancy. The problems of human relations in business were just beginning to be recognized as calling for the highest type of intelligence trained in social and economic theory and balanced by practical business experience. Beginning in the educational department of the Western Electric Company, Mr. Hopkins has, through the establishment of successive relationships with important corporations, built for himself a really nation-wide reputation as a student and practitioner of applied sociology, particularly in the realm of human relations in industry.

His task has been to work out the processes whereby the employee shall first, be wisely chosen; second, be properly trained for his task; third, be given opportunity to realize his highest possibilities in the field of his endeavor. In the natural course of this work his investigation has of necessity, covered the field of secondary and collegiate education in the United States. Few men have a wider first-hand acquaintance with American institutions of higher learning. He knows their strength and their weakness, what they aim to do, and what they actually accomplish, - and this on the basis not only of personal touch with the institutions but also of immediate and revealing contact with their product.

All of this implies an understanding of men and of books, and of the relation of learning to life,—for the teaching of which our colleges really exist. Recognition of this by business brought Mr. Hopkins many flattering opportunities. Academic recognition took the form of invitations to lecture at the Tuck School at Dartmouth and at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, and of high educational calls known only to a few. Mr. Hopkins' writings upon sociological and economic subjects have of late been increasingly frequent. He was influential in establishing associations of employment managers in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, and has been in close touch with the executive affairs of the National Society for Promotion of Industrial Education.

HIS POINT OF VIEW

With the abilities whose rare combination has brought Mr. Hopkins deserved rewards in business and scholarship there are combined personal gifts of friendly acquaintanceship, serious purpose and spiritual conviction. Contact with the community effort of humanity has convinced him that life must be for service. If the college is to fit men for life it must accordingly fit them intellectually and also spiritually for service. In his educational ideas, therefore, he becomes conservative rather than radical. He places emphasis where it might be expected that the ministerial president would place it. This is evident in the brief interview which he gave out following the announcement of his election. In this he says:

The attractiveness of the traditional colleges of among our institutions of higher learning throughout the country, has always seemed to me to lie in their distinctiveness. It is not as standardized units of a Highly specialized educational system that we are interested in them, but it is because of the heritage of their worthy traditions, their cultural atmosphere and their definite tendencies to render particular types of service.

To those of us who are the products of her influence this seems especially true of Dartmouth. Her foundation resulted from a great missionary impulse. Her progress has always been most marked through periods that have emphasized above all else the desirability of a spirit of intelligent service in men who bore her name. The value of her accomplishment in years to come will be measured by the contribution she shall make to the intellectual and spiritual forces whose guidance must be invoked in even greater degree for the wise development of our nationalism in this country.

The immediate needs of a distraught world must be accepted as the compelling opportunity of the college. Neither diletantism nor a disposition toward unintelligent effort can be tolerated as the product of the college course which monopolizes four of the best years in the formative period of a man's life. Scholarship, whether or not allessential in itself, becomes tremendously so when recognized as being the measure of the command of one's mental faculties, acquired as a result of the college influence. It is very hard to justify this influence at all if it is not thus justified.

It has always seemed to me so obvious that the method of the curriculum is so much more important than the content that my own confidence has always been far greater in the old-time classical' and mathematical training as a basis for the curriculum than in some of the more modern combinations. The value of the former in enlarging mental perspective, and enforcing mental discipline has been much more impressively proved than has the value of a great proportion of the subjects thrust into college programs in recent years.

The wide distribution of Dartmouth alumni throughout the country, and the widespread areas which are represented in her undergraduate body, make her in a peculiar way a national college as do all her traditions. Her responsibility is consequently particularly large to realize her opportunities to the full in rendering service to our national development in the years of readjustment which lie before us.

It is with such beliefs as these,—and a like solicitude with that of other Dartmouth men, that our college training may afford our undergraduates those qualities which they will later need for full usefulness,— that I have accepted the invitation to go to Hanover to join my efforts with the efforts of those long-time friends of mine there who have striven without ceasing and have so largely made the college what it is.

Thinking these thoughts, trained as he has been trained, sacrificing much worldly good for the sake of undertaking leadership in the College from which he graduated, with whose history, traditions and ideals he is saturated, and with whose educational and administrative problems he is familiar, Mr. Hopkins should make one of Dartmouth's greatest presidents.

PERSONAL OPINION OF OTHERS

That high hopes for his administration are entertained is clear from multitudes of letters, from press comments, and from honors extended.

Of the open letters the most significant to Dartmouth men is that of President Emeritus Tucker whose pleasure in the selection of Mr. Hopkins is manifest. He writes:

Mr. Hopkins is a man of strong personality, —broad and sane in his judgments, and of unusual power of initiative. I have known very few young men who have had the equal gift of foresight,—a gift which he has already turned to account in his study of the present needs and responsibilities of college education. In this regard, as in certain other personal respects, I think that he is peculiarly fitted for educational leadership.

Mr. Hopkins has a good understanding of the 'mind of a college.' He has been in close contact with college students since his own graduation. His influence over young men is direct and positive. His ethical and religious convictions are so clear and his moral enthusiasms so quick that I anticipate his readiness and ability to assume the moral functions associated with the presidency of a New England College. And as the qualities which have given him so much success thus far in executive work are personal, I am confident that he will be able to make the transfer to the administrative service of the college with very little loss.

Prof. John K. Lord gives this testimony:

Mr. Hopkins is a tremendously growing man. No one of the younger alumni, with whom I am acquainted, has developed so markedly as he in business capacity, and in the scope of his thinking and his purpose. He will bring to the college not only the .usual stimulus of personal desire for success, but an ardent, unselfish and well attested interest in its welfare.

No less generous is the tribute of Ex-President Nichols, which is as follows :

The action of the Trustees of Dartmouth College on the Presidency was taken only after the most careful and searching consideration. In Mr. Hopkins the Board has chosen a man of unusual strength and ability, a man of clear thought, firm conviction, and of pleasing and forceful personality. Mr. Hopkins has the priceless qualities of youth, and a trained capacity for hard and efficient work. He is deeply imbued with the ideals and traditions of Dartmouth, and through a long experience, first as secretary to former President Tucker and later as Secretary of the College, he is no stranger to its administrative work and organization. He is richly endowed with many human and intellectual qualities which promise success for his administration and continued strength of the College.

NEWSPAPER COMMENT

Comment of the press is uniformly cordial, and almost as unanimously favorable. Some of the papers point out that the new president is young; and that his achievement as a scholar and educator as viewed from the usual standpoint of the school man is small. Yet, these papers express a warm interest in the experiment and display what is at least an indulgent optimism.

Thus the Boston Transcript of June 14 says editorially:

Seldom has the selection of a college president rested so much on trust as that of Mr. Ernest M. Hopkins to be Dartmouth's new leader. Nearly all of the "book values" which customarily go to determine a choice of this kind are in his instance lacking. Mr. Hopkins is not a man widely known in the world of learning. Neither the lengthy of his years, nor the size of the tasks given him to perform, has yet established his reputation so that all who run may read. Notwithstanding these facts, the trustees of Dartmouth have chosen him to be the institution's next president. They have been mindful that many a man who came to high office with one reputation behind him has not been able to make another within his new duties. They have asserted their faith that the data of established accomplishment and maturity are not the only basis on which to decide so important a choice, and sought guidance from other qualities which seem to them sufficient proof of his potentiality.

The trustees' conviction that they have found the right man is so positive that it cannot fail to impart to others some of its enthusiasm. In lieu of fame writ large across the country, they have found Mr. Hopkins's reputation of the kind which bears minute inspection within its lesser compass. Every task given him to perform has been accomplished with vigor, insight and thoroughness. Through them all he has been a man of quick human understanding, and, what to Dartmouth men is a supremely important phase of this attribute, of remarkable Dartmouth understanding. Dartmouth to Ernest M. Hopkins is almost a religion. He was closely associated with it as a student and as an official during fifteen of his most formative years. More than any other man he should be acquainted, on account of his personal service to Dr. Tucker, with the ideals and policies of that former president, who seems still to hold the greatest loyalty of all Dartmouth men. Dr. Tucker warmly indorses him. He says that Mr. Hopkins will make his reputation.

The first statement from the presidentelect proves that he knows in what kind of service to Dartmouth that reputation can be made. Recognizing the progressive future which the institution must not be denied, he is resolved to maintain its status as a college and to resist the temptation to make it a university. In so doing, Mr. Hopkins correctly values Dartmouth's birthright. Expansion upon the fields of university growth would leave abandoned, or only half cultivated, the well-tilled acres of Dartmouth's normal position as a college of simplicity, where ruggedness and thorough training in a few essentials are sought before diversity. Yet this development must not mean that Dartmouth should be kept or made provincial. Directly on the contrary, it seeks and lias been increasingly achieving place as a college for all the nation. Here again Mr. Hopkins is credited by the trustees with a kind of experience which qualifies him for the task in hand. The public will be glad to share their confidence.

The Springfield Union under the cap "Dartmouth's Departure in the Choice of a President," remarks:

The trustees of Dartmouth College have made a notable departure from established precedent in selecting Ernest Martin Hopkins of the class of 1901 to succeed Ernest Fox Nichols, who resigned the presidency last November after only five years of service to accept a new chair in physics at Yale. Mr. Hopkins is not an educator in the commonly accepted sense, nor does he rank high in scholarship. In neither literature nor science has he achieved distinction. His has been a business career, yet he is not a business man as measured by the usual standards. He has managed no large corporation or other business enterprise, has not been a manufacturer, merchant or banker. The side of business that has claimed his attention has concerned problems of an entirely different order. He has been engaged in a new business profession, which for lack of a better name may be called business sociology, with a large element of psychology in it.

The ordinary efficiency expert concerns himself chiefly with methods, systems and machines. His object is to increase production at a lower cost unit, and this he has done with marked success as gauged by economic results. But he ordinarily ignores the very consideration that has most to do with the smooth running and really efficient conduct of a business; namely, the relationship existing between the directing heads and the employees. With a perfect system, modern equipment, and most improved methods, why are some businesses in a continual turmoil ? Why are they forever breaking in new hands, and therefore rendering inefficient their whole organization ? It is to the consideration of this problem inparticular that Mr. Hopkins has devoted his energies in recent years, achieving a degree of success that has attracted marked attention among those who would naturally be most interested in the sociology of business.

To pick such a man as this as the head of one of our oldest and most historical colleges is, as we have said, a departure almost in the nature of a bold experiment. It involves, however, full recognition of that new sphere of usefulness which is opening up to our educational institutions. Important as it is that a high value should be placed on scholarship, that our colleges should turn out men who will devote their lives to the pursuit of art, science, literature and theology, of far greater importance is it that the great mass of their graduates shall have a keen perception of the live practical questions now confronting civilization, and a mental equipment to deal with those questions for the common good of mankind. . .

As for familiarity with the college and its needs no man considered for the presidency had any advantage over Mr. Hopkins, who was secretary to former President Tucker for four years, and for a like period secretary of the college. . .

[The opinions of President Tucker and Professor Lord ] will have weight with Dartmouth men, as undoubtedly they had with the trustees. They will tend to remove the doubt and skepticism that many of the alumni have felt since it became known that the trustees had it in mind to select Mr. Hopkins and to depart in a radical way from those considerations which ordinarily govern in the choosing of a college president. There is among all Dartmouth men a strong sense of loyalty toward the college, and they will unhesitatingly and unreservedly give to the new president their very best support, whatever may have been their previous views in respect to the election of a man who has not been prominently identified with educational thought, or who could not lay claim to other special attributes commonly looked for in a college president. The fact of the matter is that Dr. Tucker is so beloved by Dartmouth men everywhere and so exemplifies their ideal of what a college president should be that the task of the trustees was rendered peculiarly difficult. It was so when Dr. Nichols was chosen, and it will be so until the generation who knew Dr. Tucker has passed away.

In somewhat similar vein the Lowell Courier-Citisen expresses itself thus:

The election of Ernest Martin Hopkins to be president of Dartmouth college, vice Ernest Fox Nichols, resigned, does not come as a surprise to anyone who has known the inside, even casually, for the past two months. To one unacquainted with the progress of the selection it is improbable that Mr. Hopkins's name would have occurred as even a remote possibility. Since the suggestion has been talked of, however, the real doubt has been whether or not Mr. Hopkins would consider accepting the offer, he being by nature a business man and having very attractive prospects before him. Largely untried in educational fields, and fully aware, as once being secretary to President Tucker, of the colossal difficulties in the path of a college president, and above all distinctly uncertain as to the reception of the news of his selection by the alumni body—which is always of the first importance in making or unmaking an administration—it had seemed to us entirely unlikely that Mr. Hopkins would consider the offer at all, although it became increasingly evident that the trustees were bent upon making it.

It is given to few men to be an obvious choice for such a position as this. One may count the instances of perfectly plain foreordination on the fingers. William Jewett Tucker, who served Dartmouth for fifteen years between 1894 and 1909 and who built the college up from a little one to a great one, was the most conspicuous example of obvious designation by every circumstance. In the average case, as in this of Mr. Hopkins, it is quite otherwise. The incoming president has his record all to make, unassisted by any antecedent probabilities, and very probably against a considerable degree of downright skepticism at the start. One recalls the case of President Eliot, although it is not by any means an exact parallel. Dr. Eliot started his memorable career as president of Harvard roundly opposed, and proved to be one of the greatest educators of his day. Candor compels full recognition of the fact that Mr. Hopkins will certainly undertake his task handicapped by much the same initial skepticism, to call it nothing more; but common fairness demands of Dartmouth men that they suspend hasty judgments and let the new president have a free chance to prove his capacities, as Dr. Eliot so conspicuously proved his.

President-elect Hopkins is a young man, a graduate in the class of 1901. He served from that year through 1909—the closing year of Dr. Tucker's presidency—as secretary to that most successful and inspiring leader; and his selection by the trustees to assume the presidency now is understood to be on the strong recommendation of Dr. Tucker himself, now living quietly in Hanover as president-emeritus. Dr. Tucker's judgment, after nine years of close personal association with Mr. Hopkins, was certainly not to be set lightly aside and the trustees have chosen to give it weight exceeding that of any other element offered for their guidance in this delicate matter. There was a distinct demand that the presidency be given to some Dartmouth alumnus, and the hope must be that the mantle of Dr Tucker has indeed fallen upon the newly elected president. The task is a big one—one of the hardest in the world; but at least it is not so discouraging to attempt to follow Dr. Nichols as it was for Dr. Nichols to attempt to follow successfully the incomparable regime of Dr. Tucker.

Zion's Herald of Boston shows signs of actual pain. In its issue of June 21, after repeating- the news items concerning the President-Elect, it remarks:

Ex-President Tucker, Prof. John K. Lord, and President Nichols highly commend the president-elect. The election will, however, surprise many alumni and ardent friends of the institution. The trustees evidently have sought a business head for the college rather than the historic educator and conventional representative of old Dartmouth. Is the institution quite in line with its traditions in the election of Mr. Hopkins to the chair made famous by such men as Nathan Lord, Asa Dodge Smith, and William Tucker?

The Journal of Education discusses the matter briefly as follows:

In the selection of Ernest Martin Hopkins, a graduate of Dartmouth of fifteen years ago, as successor to President Ernest Fox Nichols, who goes to Yale as professor, the trustees have given the academic world its greatest recent surprise. Not even the 1916-1917 "Who's Who" has heard of him, but his success is assured on the ground that the trustees have a greater responsibility than they would have had had they taken a man already credited with corresponding success. A man thus selected never fails, and no one fails at Dartmouth.

Nowhere else is there any note of question; only that of frank approval. It is particularly pleasant to find the press of New Hampshire so cordially disposed as it is.

Says the Manchester Union, under the caption, "Promising for Dartmouth":

So keen is New Hampshire's interest in Dartmouth, and so great is the state's pride in her growth and prosperity, that we may sometimes have overlooked the fact—though we have by no means forgotten it—upon which President-elect Hopkins touched in u , statement, following his choice by the board of trustees. Dartmouth, as he justly points out, is peculiarly a national college, drawing her students from all parts of the country and sending her graduates to every State in the Union. The responsibility of the college, he declares, "is consequently particularly large to realize her opportunities to the full in rendering service to our national development in the years of adjustment which lie before us." It is well to be reminded of this, even though, while we claim Dartmouth as our own, there has been, and is, no selfishness in New Hampshire pride in the institution at Hanover. Indeed, in geat measure it is based upon the service the collag is rendering to the country at large as well as to the state.

It is hardly necessary to say that all New Hampshire wishes the new president well. It has every reason to believe him especially equipped for the task which lies before him. He was born in the state; he is a graduate from Dartmouth; he bore his full share of student activities; after his graduation he was for years identified with the administration of the college affairs. As secretary to President Tucker, and then as secretary of the college, he gained an insight into the problems which Dartmouth must solve, some of them problems of her own, others problems she shares with sister institutions of learning. He has kept in touch with the undergraduate body and with the alumni as well. He enjoys the respect, the regard and the confidence of both. His recent investigations in what has been termed the "human relation in industrial organization" have added vastly to his store of knowledge of subjects of the highest importance to the welfare of the nation.

The American college president of today is put to the test of great opportunity and great requirements. Much is demanded of him. But, as it appears to us, rarely has an executive been placed at the head of an institution of fine history, glorious tradition and splendid development, better trained for his duties and with more promise of high usefulness than is given by Ernest Martin Hopkins, president-elect of Dartmouth college.

Of Dr. Nichols, the retiring president of Dartmouth, it is impossible to say too much byway of commendation. The seven years of his administration have been years of genuine progress and achievement for the college. For those who are familiar with Dartmouth affairs, it is enough to say that he came to the institution to succeed the revered President Tucker, and has done it worthily. Strikingly important movements, calculated to promote the welfare of the college in its internal economy and its external relations, have been inaugurated, and their value has already been demonstrated. They have attracted favorable attention in educational circles throughout the country, and are destined to wield wide and beneficent influence. Like Mr. Hopkins, Dr. Nichols came to Dartmouth with a knowledge of her traditions, her aims and her needs. He found the college, under the splendid leadership of Dr. Tucker, making rapid strides toward a realization of her highest and best ideals. He took up the work where Dr. Tucker laid it down, and, owing in very large measure to his combination of energetic initiative and level-headed judgment, the best possible advantage has been taken of the momentum attained under his predecessor, and the progress of the college has been correspondingly continued and increased.

Dr. Nichols returns, in the full vigor and enthusiasm of young manhood, to the fascinating work of investigation in physical science, in which field he has acquired enviable recognition and honor; carrying with him the respect and affection of all who love Dartmouth and cherish her traditions and her aspirations. There is encouraging reason for the belief that the administration of President Hopkins will as worthily succeed that of President Nichols, as the latter administration has succeeded that of President Tucker—and this is saying much.

The Leader of the same city says:

No two colleges are alike. An old institution like Dartmouth, born and reared in circumstances which tended to impress upon it strongly marked individuality, and now doing its great work in the full vigor of progressive maturity, is different from any other educational institution on earth. It has its own distinctive characteristics which are both of the form and of the spirit—its features and its personal character—just as it has its own history and traditions. A president of Dartmouth then, must have certain qualifications which cannot be stated in specifications to the education market. Any one of a dozen men might have the scholarly accomplishments, administrative ability, moral qualities and athletic interests required for any one of many schools, just as he might be of the desirable height, age, and complexion for something else, and yet not be fitted at all for a Dartmouth presidency. So, too, an election to this office is in a degree experimental.

The Dartmouth trustees have made their choice of a successor for Ernest Fox Nichols, a man who has filled the office with distinction, and it falls upon Ernest Martin Hopkins. Apparently the element of experiment has been reduced to the minimum. He is a New Hampshire and a Dartmouth man who has served as secretary to President Tucker and then in a similar capacity for the college. He ought to know the Dartmouth mind, in his statement of educational policy he talks as if he does know it. He is young, but granted that he possesses the essential qualities of a Dartmouth head this only means that he will mature in the exercise of these qualities, being enriched from year to year by the school as he gives it his ever enlarging service of leadership.

As to his qualifications, if the judgment of the trustees needs endorsement with the great Dartmouth public, that of President Tucker will suffice. No man knows the Dartmouth spirit better than he, and he knows the president-elect.

This much is certain, Mr. Hopkins is not only acquainted with the college traditions but his associations with Dartmouth are of recent years. He knows the college as it is today, and may be expected to carry to full development the new undertakings begun by his distinguished predecessor while maintaining the ancient standards that have made it famous in the past.

The Concord Monitor is no less friendly. It remarks:

Ernest Martin Hopkins, new president of Dartmouth College, has many qualifications for success in the position to which he has been chosen. He is a young man; a native of Merrimack County, New Hampshire; a graduate of Dartmouth College; the closest personal and administrative associate of President William J. Tucker during Dartmouth's golden age; the man who above all others has brought the great body of alumni into effective and immediate touch with the college of today; a man of ability, training and success in both business and education; a man of ideas and of courage, of pleasing presence and of untiring industry; and, above all, a man of the highest personal character, a man who should be able to influence the undergraduate life in a degree second only to that which made President Tucker so powerful an instrument of good.

His native state, the home state of the College, should and will lead the Dartmouth constituency in warm hopes for, and staunch support of, the administration of President Hopkins.

The New England press not already quoted expresses itself variously, but to the same general effect of good will and approbation as the following selections clearly indicate:

The Boston Herald:

Dartmouth is the first New England college to choose for its president a man whose experience and achievement have been primarily in the business field.

It is not many years since the selection of other than a minister for a college presidency would have been unthinkable. There was much wagging of distressed heads when a young chemistry professor became president of Harvard. That innovation was soon followed by such general yielding of higher education in America to the influence of German university ideas, that the conception of the scholar virtually supplanted that of the minister as the traditionally suitable college head.

Yet the German theory has not, from the first, been without opponents, who accused the 'American college of making a fetish of bloodless scholarship and the materialistic point of view somewhat necessarily involved. They have questioned the propriety of adopting this as the compelling force in undergraduate institutions, which are now preparing fewer men for the learned professions than for service through ,the medium of business.

The consciousness that business is something very much greater than processes of trade is dawning. Its problems of production and distribution appear woven inextricably with those of human relations, national and international. The making of this consciousness socially operative will be, perhaps the greatest task of the present century. America's share in it will impose on the college a task of leadership.

The Boston Journal:

Dartmouth trustees are to be congratulated on their determination to prove the courage of their convictions by choosing Ernest Martin Hopkins, of the class of 1901, successor to the retiring president, Dr. Nichols.

Dartmouth is an institution of which all New England is proud, not only because of its splendid past but also because of the still more vital fact that it is today playing a big part in the molding of American youth. The Dartmouth of today stands in the front rank of American colleges, and in view of its widespread influence, especially upon the young men of New England, the trustees have good cause to rejoice that they have found so ready a solution of the presidential problem.

For Mr. Hopkins is indeed a son of Dartmouth, saturated with the peculiarly lively and altogether admirable Dartmouth spirit; possessing in a high degree the democratic qualities that give Dartmouth so much of the character that appeals to the younger America; intellectual as President Nichols testifies, yet intensely human, which, we say, sums all the Dartmouth qualities. He has been more or less intimately connected with Dartmouth affairs, as student, secretary of the college and officer of one of the alumni associations for nearly twenty years, yet he is on the sunny side of forty.

Small wonder the trustees were unanimous ! College presidents home-made, so to speak, and yet amply qualified to meet the exacting demands of office, are not to be found every day. We should say that the trustees served Dartmouth very well indeed.

The Christian Science Monitor

Again a layman has been chosen as head of Dartmouth College. But he had a clergyman for a father, and he is a graduate of the college, knowing its" alumni better probably than any other man whom the trustees could have named. So that while there is to be no return to the old tradition of a clerical president, there is the promise of a man coming to power whose emphasis will be upon ethical and spiritual values, learned first as a pupil and later as the confidant and helper of William J. Tucker, the greatest of the latter-day executives of the colwhom the "New Dartmouth" is due.

The grounds for the belief of such promise are the definition of his conception of education, and of Dartmouth's place as a college, which Ernest M. Hopkins, the president-elect, has given to the public and to the alumni. Not for him the vocational and utilitarian conception of collegiate education, or of the curriculum that is so inclusive that the institution cannot possibly meet its catalogue pledges. The college, as he sees it, is to deepen and heighten, quite as much as to make broad, the outlook of the individual scholar. Mr. Hopkins is by no means sure that the older, concentrated and uniformly binding course of study did not have a better disciplinary effect upon the student, and turn out better educated men, than some of the experiments with liberty to elect studies have produced.

As Mr. Hopkins, more than any other man, has had to do with organization and enlistment of the alumni in support of the college, and as he has had a large part in shaping the policy defining what the relations between undergraduates on the one hand and teachers and administrative officials on the other shall be, he will come to his new duties finely equipped for two of the most important tasks of a college president. Alumni and undergraduate confidence will not have to be won. He has that trust and respect now. Mr. Hopkins knows what the recent graduate is thinking about as he enters the outside world. A former official of the college, and kept very close to the seat of power by President Tucker, Mr. Hopkins will have only to take up reins that he once handled and see what he can do in guiding an institution of firmly held moral and pedagogical traditions and yet with an independent sort of teaching force and student body.

Nor will the college suffer in any way because Mr. Hopkins, with all his many acts of service to his college since he was graduated, also has been experimenting in practical ways with business and manufacturing. He now knows far more about these subjects, on the theoretical side at least, than do most persons who are recalled to assume the serious administrative problems of a modern college. He can be counted on to deal sympathetically with such genuine trends in the field of education as the Tuck school of business administration at Hanover, stands for. But evidently -he is not going to be driven, by any contemporary movement for preparedness or efficiency, to the conversion of Dartmouth into a military or a business college. Williams College and Amherst College will not fail to note that their old-fashioned ideals are to have a new champion.

The Boston Post:

In choosing unanimously Ernest M. Hopkins for the high office of the presidency of Dartmouth College the trustees of the institution have gone into realms of accomplishment hitherto not thought of in connection with the position. Mr. Hopkins has made his, mark in the conduct of business, and yet;, not as a business man in the commonly accepted term. He has studied and come to learn the human equation as it impinges upon all business; he has specialized more in the soul of it than in the head. That this is a qualification ripe for the great task ahead of him all Dartmouth men will gladly believe.

President-elect Hopkins has youth, burning enthusiasm for Dartmouth, the most complete knowledge of her processes and needs, and an ability that is relied upon to prove itself fully equal to the things he sets himself about to do. And we can assume that he will find the support of Dartmouth's traditionally loyal sons eagerly and confidently given him.

The Springfield Republican

Again New England is to have a President Hopkins. In order to secure him the trustees of the New Hampshire institution have left the realm of educational thought and accomplishment and gone out into the practical world of business. Mr. Hopkins has been a believer in modern efficiency methods of conducting business, and it is to be assumed that he will seek to apply them in his relations with faculty and students. The unanimity with which the call was extended expresses the confidence of the Dartmouth trustees that they are doing the right thing for the college. In President Tucker Dartmouth had a leader in education and life fit to rank with Mark Hopkins of Williams. Other New England institutions envied Dartmouth when Tucker was at its head. It appears that the venerated ex-president is also pleased with the selection of a successor to Dr. Nichols, and that is a certification worth having.

The Providence Bulletin:

Dartmouth College, which has been looking for a new president for several months, following the resignation of President Nichols, who desired to take up his special work as physicist, again and accordingly accepted a call to a chair at Yale, has chosen as Dr. Nichols' successor, a young man, Ernest Martin Hopkins, not yet thirty-nine years of age.

Mr. Hopkins, unlike his predecessor, is a Dartmouth man. He was graduated at Hanover fifteen years ago and for the first few years after his graduation acted as secretary of the president. Later he was made the first incumbent of a new office, that of secretary of the college. Thus he is familiar with the administrative feature of the college problem—a feature of increasing importance everywhere today.

In his statement of educational principles, as it may be called, the new President puts emphasis on the cultural side of the curriculum. He is inclined to stress the method rather than the content of the instruction a college gives. He recognizes the peculiar reputation enjoyed by the more typical "old-fashioned" colleges in this part of the country by reason of their individuality, as opposed to the over-standardization of some other institutions of the higher education. He thoroughly believes in Dartmouth and its future—and brings to his new post the enthusiasm of youth in addition to a considerable training and experience.

Dartmouth has made great numerical strides in the last few years. It is now one of the larger colleges of New England, with a student body approximately as large, indeed, as that of Princeton University. Its friends are devoted, its situation though remote is inspiring, and it is no wonder if Mr. Hopkins accepts with alacrity the flattering offer to become its head.

The Providence Journal:

Ernest Martin Hopkins becomes at the age of thirty-eight President of Dartmouth College. He is far from being the youngest college executive on record, but he is more youthful than most of our New England college presidents were when they took up their present tasks.

Unlike his predecessor, Ernest Fox Nichols Mr. Hopkins is a Dartmouth man. That will be a source of strength to him in his contact with the alumni and the undergraduates. He has had a valuable training on the administrative side of a college executive's work, for he served several years after his graduation as secretary to President Tucker, and later was appointed to the new post of secretary of the college. In recent years his experience has been of an unusual character for prospective college presidents. It has consisted of work with "large industrial corporations as an expert on human relations in organization." In his new office he will find many calls to put this experience into practice.

In spite of his connection with industrial corporations, we find Mr. Hopkins laying stress on the cultural side of undergraduate training.

At Hanover, as at Williamstown and Amherst, the educational problem is not the same as at Providence, Cambridge and New Haven. In every large center of population the vocational element in the problem must be emphasized. But there is room for both ideals in our American institutions of the higher learning.

Dartmouth has experienced a great growth in the number of its students in the last few years. It has a loyal alumni body and an accumulating wealth of pleasant traditions, Mr. Hopkins is to be congratulated on the opportunity that has come to him, and it looks as if Dartmouth might safely be congratulated, too.

The Providence Tribune:

Industrial America is evidently the chief plank in the platform of the new President of Dartmouth College, Ernest M. Hopkins, who is the youngest man to be placed at the head of a large institution in many years. Mr. Hopkins has looked about the world more than other teachers have and with a different method of considering the ways of men and success.

He says that twenty years ago from two-thirds to three-fourths of the boys who were in college were preparing for professional careers, but that now from fifty to seventyfive per cent of the graduates of colleges go into industrial work. Therefore, he argues, devolves upon the colleges to teach what will be of service in later life in the industries, and there is a vast difference between that and the older ways.

What he considers the difference is not exactly what many others think, and perhaps there is a peculiar significance in the Dartmouth man's view which may not flatter the professions, for he says: "It becomes, therefore, a responsibility of the colleges which are sending so many young men into the business world to develop in these men breadth and depth of intelligence." The old idea was that the professional men should have the broadening and deepening applied to them as a special privilege and that anybody could do business.

The press outside of New England shows a similar spirit to that within. The best of the editorials thus far encountered are the following:

The Chicago Post:

Ernest Martin Hopkins, the new president of Dartmouth, represents an interesting departure in the selection of college presidents. He comes to his academic position from the arena of commercial and industrial struggle and achievement. For six years he has been associated with such big concerns as the Western Electric and the Bell Telephone in the capacity of expert adviser on organization, the treatment of employes and the improvement of efficiency in production.

Back of this experience he has his academic training at Dartmouth and eight years of service as secretary to its former president, Dr. Tucker. During those years he mastered the executive and administrative side of college life.

Youth is another asset that Mr. Hopkins brings to his new work. He is not yet forty years of age.

These things point to an interesting and useful career in which the new president should be able to achieve much in relating the work of higher education more directly to the practical problems of a country still greatly immersed in the affairs of industry and commerce. That there may be a culture of business as there is of art and letters and science it may yet be the part of America to demonstrate. Certainly recent years have gone far to break down the barriers between the academic and the practical, the commercial and the professional spheres of effort. Both have been enriched by the process. A finer idealism is manifest in the business life of the country, and a greater sense of reality and a more careful precision of thought are functioning in the study and class room.

To enter upon a career so promising in its possibilities, with an experience as varied and broadening, and while youth is still one's portion, is an opportunity to be envied.

The Rocky Mountain News of Denver:

Ernest Martin Hopkins, the new president of Dartmouth, represents an interesting departure in the selection of college presidents. He comes to his academic position from the arena of commercial and industrial struggle and achievement. For six years he has been associated with such big concerns as the Western Electric and the Bell Telephone in the capacity of expert adviser on organization, the treatment of employes and the improvement of efficiency in production.

Back of this experience he has his academic training at Dartmouth and eight years of service as secretary to its former president, Dr. Tucker. During those years he mastered the executive and administrative side of college life.

Youth is another asset that Mr. Hopkins brings to his new work. He is not yet 40 years of age. .

These things point to an interesting and useful career in which the new president should be able to achieve much in relating the work of higher education more directly to the practical problems of a country still greatly immersed in the affairs of industry and commerce. That there may be a culture of business as there is of art and letters and "science it may yet be the part of America to demonstrate. Certainly recent years have gone far to break down the barriers between the academic and the practical, the commercial and the professional spheres of effort. Both have been enriched by the process. A finer idealism is manifest in the business life of the country, and a greater sense of reality and a more careful precision of thought are functioning in the study and class-room.

To enter upon a career so promising in its possibilities, with an experience as varied and broadening, and while youth is still one's portion, is an opportunity to be envied.

The New York Christian Advocate:

Another Baptist minister's son, Ernest Martin Hopkins, steps into the sun as president of that fine old New England college, Dartmouth. He is a layman, and is expert on human relations in organization." In this function he has served the Western Electric Company, the American Bell Telephone Company and other great industrial corporations. Without quite understanding all the duties which adhere in such an employment, we should suppose that the office was improvised to supply the "soul" which corporations are said to lack. If there is any sort of group of "human relations in organization" that will profit by expert and sympathetic oversight, it is that which comprehends the board, the faculty and the student-body of an American college. Hopkins is the hardest of names to add educational luster to, with Mark and Johns and others already illustrious, but those who know Ernest M., believe he will maintain the standard.

The New York Nation:

Dartmouth appears to have made a happy choice in her new president. While his experience has been chiefly that of a man engaged in affairs of business Organization, the statement issued by him on the occasion of his election bespeaks a clearness of view as to the aims of his college which is often wanting nowadays in men taken from the academic ranks to fill like positions. The president-elect, Mr. Ernest M. Hopkins, says at the outset:

"The attractiveness of the traditional colleges of the East, among our institutions of higher learning throughout the country, has always seemed to me to lie in their distinctiveness. It is not as standardized units of a highly specialized educational system that we are interested in them, but it is because of the heritage of their worthy traditions, their cultural atmosphere, and their definite tendencies to render particular types of service."

That the significance of the college influence upon a man must be measured above all by the command it has given him of his mental faculties, and that, viewed from this standpoint, the value of the old-time classical and mathematical training "has been much more impressively proved than has the value of a great proportion of the subjects thrust into college programmes in recent years"— all this sounds very good, especially when coming from a man of thirty-eight whose reputation for practical ability rests chiefly upon his work as a business executive or organizer.

The Outlook, New York:

College presidents are no longer selected solely from the so-called professional ranks. The new president of Dartmouth comes to his office from a life very far removed from that of the theologian or scholastic recluse, formerly the typical college president. Ernest Martin Hopkins has been engaged since his graduation from Dartmouth in 1901 part of the time in academic life and part of the time in wrestling with the most complex of modern industrial problems—the problem of the relation of employer and employee.

Dartmouth itself in recent years has illustrated the wide variation in vocations from which men are called to the college presidency. Mr. Hopkins's immediate predecessor, Ernest Fox Nichols, did not even have the' Arts degree. He gained his eminence in the field of pure science, particularly by measuring planetary light and heat. Mr. Nichols's immediate predecessor, on the other hand, was Dr. Tucker, who, though a writer on social and economic questions, was, when he became president, primarily a clergyman, a preacher, a theologian. In contrast to both of these, Mr. Hopkins has gained his experience in the world of business and manufacture. It is, however, not on the material but on the human side of business and industry that he has been active.

After his graduation from Dartmouth Mr. Hopkins was appointed secretary to President Tucker, and for eight years had experience in academic life on the executive and administrative side. In 1910 he undertook a new line of work, but not as different from his former experience as it might at first seem. He associated himself as staff worker with various corporations—among them the Western Electric Company and the Bell Telephone System. He was among the first to interpret the functions of the employment manager, and helped to found the Association of Employment Managers in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. Such a problem, for instance, as that of the relation of labor unions to efficient production is one that may be treated theoretically in books or practically by the management of an industrial plant. It is the practical side of such questions with which Mr. Hopkins has been dealing. The arbitrary discharge of an employee—to cite another instance—has usually been left in the power of department heads. To replace this by a scientific study of the causes for discharging employees, and to substitute a rational, systematic method for the arbitrary will of a foreman, has been the sort of problem with which Mr. Hopkins has dealt.

This work on the human side of industry and business involves an educational process. It is just as much educational as the executive work connected with a university, and, indeed, calls for some of the methods of the university laboratory and class-room. Mr. Hopkins's experience, therefore, may be said to be directly in the line of the duties which he is now called upon to perform.

,can told from photograph reproduced on another page, Mr. Hopkins is a young man. He is not yet forty years of He has been a loyal son of Dartmouth, and particularly active in alumni affairs. He founded the "Dartmouth Alumni Magazine," and for some time was its editor. He believes more in the importance of "the method of the curriculum" than its content, to use his own phrase, or, to put it more colloquially, he believes that the way a subject is taught is more important than the subject itself. He has been a special student in vocational training and vocational guidance.

The selection of such a man illustrates not only the broadening of the American college, but also the broadening of the spirit of American business and industry. The barriers that used to be so firm between trade and science and the so-called professions are disappearing. The mellowing effect of the "humanities" is to be seen in business and in science, and the influence of business and of science in the direction of reality and exactitude is evident in those circles that once were regarded as safely and serenely academic.

The Ithaca News:

How a man's knowledge of the daily routine of a high position may convince a board of trustees of his fitness to fill it, is indicated in the selection of Ernest M. Hopkins as president of Dartmouth College. The appointee was known to be familiar with the official workings of the institution from having been a former president's secretary. He thus took a path of advancement along which business men are found oftentimes to have gone, and more than any other kind, perhaps, bankers. Sir Edward Walker, head of the Canadian Bank of Commerce, has pointed out that the discontinuance of men in the position of private secretary to the bank president causes a break in the chain of promotion which needs mending. According to his view, a candidate for first honors must know his duties from the inside, and fairness demands that he should be given an opportunity to learn them.

The Philadelphia Bulletin:

The trustees of Dartmouth College have elected Ernest Martin Hopkins as president of the college, and in a statement issued by them concerning his qualifications for his new office, we find this noteworthy paragraph:

"In 1910, he resigned his secretaryship at Dartmouth to become a student and practitioner of applied economics, parcularly in the field of human relationships in industrial organization. Academic recognition of his achievement in this field has come to him in the form of lectureships at the Amos Tuck School of Administration and Finance at Dartmouth College, and the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania."

There is a new and stimulating conception suggested here as to the mental equipment necessary for a modern college president. To use President Wilson's phrase, it is distinctly "forward-looking" in its demand that a college president must be something more than a profound scholar, something else besides a collector of large endowments. There can be no gainsaying the fact that "in the field of human relationships in industrial organizations" lies one of our most vast and undeveloped areas for mental evolution and effort. Citizens of tomorrow must be prepared to answer categorically the questions raised by Colonel Roosevelt's doctrine concerning social justice; and these citizens are now the students and are to continue to be the students at our universities and colleges during the generation that is to take over the management of the industrial organizations which we have brought to physical and financial perfection. It remains now to bring "the human relationships" also to a state as near perfection as lies within the power of our modern teaching of altruism and social ethics.

President Emeritus William J. Tucker amplifies the statement of the trustees by saying that Mr. Hopkins has a good understanding of "the mind of the college." We take it that he implies that the minds of colleges are subject to change and growth, and that Mr. Hopkins is in tune with the progressive tendencies among students of this day. Indeed Mr. Hopkins gives in an interview a notion of what he expects of coming graduates when he says that "the immediate needs of a distraught world must be accepted as the compelling opportunity of the college. Neither dilettanteism nor a disposition toward unintelligent effort can be tolerated as the product of the college course which monopolizes four of the best years in the formative period of a man's life." In other words, the time has passed when irresponsible youth should be allowed to look upon a college education as a finishing touch of polish for a gentlemanly career and as preparatory to leadership in the fashionable walks of life.

The Philadelphia Ledger:

Youth is served, as well as the interests of higher education, in the choice of Dr. Ernest Martin Hopkins as president of Dartmouth College. At the age of 38, he is said to be the youngest college president in the country; but he has been tested and not found wanting, and he is chosen, not because he is young, but because he has already "made good" and will improve upon, his useful, fruitful record. Aside from his varied affiliations with his alma mater, Doctor Hopkins is versed in the book of human nature and he has been a student of problems of industrial welfare. His former associates in Philadelphia wish him the fullest measure of success in the new connection and anticipate for the college that has called him to its service an era of prosperity under his firm, wise guidance.

The Seattle Times:

Dartmouth College has set a new example in the selection of college presidents. It has been the custom of educational institutions to choose their executive heads from the ranks of the professors. Years ago it was thought essential that he should also be a clergyman. In more recent years some attention has been paid somewhat to the business qualifications of a prospective president as well as to his standing as an educator, but the latter was still deemed essential.

Ernest Martin Hopkins, the new president of Dartmouth however, was selected from the commercial and industrial walk of life. Although a graduate of Dartmouth and possessing an intimate knowledge of the administration of his alma mater, by reason of having served at one time as secretary to its former president, he comes directly from the avenues of business.

For some years he has been associated with such concerns as the Western Electric and the Bell Telephone Companies as expert adviser on organization, the improvement in efficiency in production and treatment of employes. He is essentially a business man and his administration may reveal to Dartmouth and other institutions of learning a way to render a better and broader and more effective service in their relations to the practical side of life.

At any rate, his selection is a frank recognition not only of the fact that the administration of a college has become a business proposition, but of the fact also that the institutions of higher education must get closer to the business, commercial and industrial problems of men.

Culture in this age means more than knowledge of letters and science and the arts. It means a practical application of these worthy attainments.

PRESIDENT HOPKINS HONORED

Following the announcement of the election of Mr. Hopkins to the presidency of Dartmouth came immediate recognition on the part of fellowNew England colleges. On June 21 Amherst conferred on President-Elect Hopkins the degree of Doctor of Letters. A week later Colby College conferred the degree of Doctor of Laws.

In each instance the ceremonial was characterized by tributes that displayed a keen appreciation of the things which the recipient of the degree has already accomplished and of what may be expected from the directing of his energies to the task of college administration. At Amherst, Talcott Wiiliams, LL.D., Dean of the Columbia School of Journalism presented the President-Elect with the following words:

"Ernest Martin Hopkins, administrator in the task of education, experienced in the management of college affairs, constructive organizer of student and alumni activities in his alma mater, proficient in the application of education to the work of great corporations. On behalf of the faculty and trustees of Amherst, as proof and token of affectionate regard for a sister college, I ask you to confer on him, the newly-chosen president of Dartmouth College, the degree of doctor of letters."

The applause which greeted the conferring of the degree attested the popular appreciation of the man and of the deserved honor bestowed upon him. A similar outburst of enthusiasm greeted Mr. Hopkins at Colby College. Here he was presented by the Honorable Leslie C. Cornish, LL.D., of the Supreme Judicial Court of the State of Maine, who spoke thus:

"Mr. President: The Trustees have voted to confer the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws upon Ernest Martin Hopkins, lately elected President of Dartmouth College. His remarkable achievements in the field of applied economics are abundant prophecy of the better correlation between college training and practical life which President Hopkins will help all of us to understand and achieve."

It is quite possible, however, that none of the tributes and honors which have so abundantly come to him since his undertaking the presidency of Dartmouth has brought to Mr. Hopkins a keener personal satisfaction than a small rite performed in Boston on the night of July 7, by a group of old time friends.

Chief part of the rite was a dinner at the Union Club given in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Hopkins and arranged under the guidance of Trustee and Mrs. Edward K. Hall, the party consisting of fifteen persons. At the close of the dinner President Hopkins was duly presented and received at the hands of the presiding officer the honorary degree of Doctor of Good Comradeship.

It was, of course all in the way of expressing the affection of long time intimates. Its significance began there but it ended elsewhere: President Hopkins is a man of large ability, of unusual experience, of specially valuable training. But if that were the only or even the chief part of his qualification for his task it would be insufficient. That which vitalizes his other qualities and makes them influential among men is his individual personality. Few possess in greater measure than he that quality of good comradeship which finds ready paths of sympathy with all manner of persons; few have such genius for acquaintanceship, such convincing power of friendly influence. During his service as secretary of the College he exerted a profound influence upon the student body. They held him in a peculiar mixture of affection and respect. As THE MAGAZINE expressed it in an editorial on Mr. Hopkins, written in the fall of 1910: "he was friend and adviser to many individuals, the important counselor of many groups." Whatever the immediate aspects of the case, in the long run, the administration of a president of Dartmouth will be estimated by its direct influence upon student life and opinion. If a judgment based upon long observation may at all be trusted the promise of President Hopkins in this respect is high, and certain of fulfilment.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE TRUSTEES' ANNUAL MEETING

August 1916 By JAMES FAIRBANKS COLBY, JOHN E. JOHNSON, J.W. NEWTON3 more ... -

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT

August 1916 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

August 1916 By RICHARD F. PAUL -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1866

August 1916 By HENRY WHITTEMORE -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE YEAR IN REVIEW

August 1916 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1891

August 1916 By F.E. ROWE

Article

-

Article

ArticleChase's History Reprinted

November 1928 -

Article

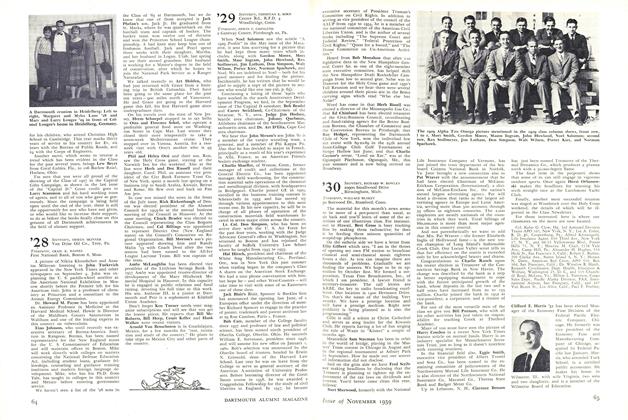

ArticleClifford E. Harris '31 has been elected

November 1959 -

Article

ArticleRE: THE DARTMOUTH

April 1934 By Jerry Alan Danzig '34 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH PARENTS

January 1945 By LT. COL. WILLIAM H. COULSON, AUS -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

April 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Article

ArticleCurriculum Change

DECEMBER 1931 By W. H. Ferry '32