The following article appeared in the Lowell Courier-Citizen of July 5, from the pen of the editor Philip S Marden '94. It is printed here as an illustration of that spirit of unity that keeps a class together as long as a member of the class survives. The writer does not mention the fact that the last Commencement was distinguished by the gift of $25,000 to the College from the class of 1894. In view of the brotherly solidarity indicated m this article such a contribution is not surprising. EDITOR.

"Say, Tuffy, remember when old Type said, 'Now, gentlemen, the next .picture will be of a fossil of the Devonian age' — and they threw a picture of old Type on the screen?"

Of such comments is reunion conversation.

If you take 60 or 70 men who summered and wintered each other for four tempestuous college years and bring them back to the alma mater for a reunion after 25 years of more or less constant separation, you will find them fertile in reminiscence — not usually of things that were supposed to be carried away from the Pierian spring, but of trivial incidents such as that cited above, which went to make life joyous and memorable. The ridiculous things, the failures, the misdemeanors all bulk larger than the purely educational ones. For instance the only thing I recall from my geology course is the fact that Bug Allen, now a judge, one day in recitation picked up a coal hod swung it three times around his head and then let it fly through a double window — for no apparent purpose, but to his own undying glory as a disturber of the peace. Every little knot of men sitting under the shade of immemorial elms will be heard chattering quietly enough — with punctuations of laughter — about just such things as that. And virtually every sentence opens with, "Do you remember ?"

Reunions come to be rather solemn affairs after a while, but that phase of it is still soft-pedalled even in that 25th and 30th of those occasions. To be sure, one is conscious of getting on — but there is the 50-year class back, too, and not acting as if it felt very old. Why worry? Yet? "Carpe diem," as Horace sagely remarked on more than one occasion. Let's hang the almanac's cheat and the catalogue's spite! Or, as a classical. age once put it, "Dum vivimusvivamus" — which is, being interpreted, "Go it while you're young!"

Our class turned out at its 25th reunion looking very little older than it did five years before. It had come into certain honors — boasting a state governor, a. congressman, a judge, a captain in the navy, a professor, a brace of mayors, sundry magnates of industry — all arrived at this mature estate within the year and therefore giving to our gathering a more august atmosphere than formerly — but on the whole we didn't look very much changed. A few might honestly claim to look about as young now as when they graduated — barring the fact that to accomplish this it is usually necessary to keep the head covered. Baldness or grayness is prone to be thrust upon us all — and of course the average run of men can point with varying degrees of apprehension to a rush of dignity to the waist-line. But hang it, that's only the body! The thing is, how's your soul ? Has that begun to get gray and crabbed? Or bald and cynical? Or is -fatty degeneration of the appreciations setting in? If so, it is never revealed at any reunion.

I remember that when I graduated 25 years ago the class of '74 was back for its 20th reunion. Lor' what graybeards we thought them! Just about ripe to pick! And here we are, five years older than they were then, ready to sit up all night with the youngest class of all, and not conscious of any serious decline in our powers. Even the fact that Jim and Bill have sons in the sophomore class doesn't greatly impair the feeling. Matt and Fatty and the rest have boys entering college next fall — in fact most of them who have any boys will find themselves possessed of young alumni before another reunion rolls around; but we're going to feel pretty young even then, with 50 well behind us and 60 coming on apace. If I live, I shall refuse to be solemn.

I get a sensation of solemnity from little things, such as tearing off a monthly leaf from the calendar or from looking on the face of a 30-year bond. The latter always amuses me by its careful insistance that it matures in 1943 A. D. — as if some legalistic quibbler might set up the claim that it had meant B. C. all the time. But usually the amusement is overcome by the feeling that when the last of those coupons is cut I may be myself with yesterday's sev'n thousand years. Even if I live I shall be senile — and may be the bolsheviki will have annulled the bond before then and left me penniless besides! It's a solemn thing to face a 30-year bond, even when it belongs to some one else. It ought to be more solemn still to go back to your college where calendars are torn off for the alumni five years at a time — but somehow it isn't. I remember good old Judge Cross, '41, coming back for his 73d commencement, and how his cheek was like a rose in the snow. So mote it be with us all! And that's a long way off too, praise God! Even today we can find a reverend professor or two who used to hold us in thrall — most of them retired, but still in residence as befits the retired don. Tute, and Dude, and Gabe, and Johnny K., and others — men before whose lightest nod we were wont to quail — now account it a pleasure to come and sit with us under the trees on a cool and sequestered sward and do a bit of reciting to us. One brazenly calls them by their nicknames to their face — and they seem to like it, bless 'em. Happy the professor whose nickname is a symbol of love and affection — as most of them are.

I like the substantial mummery of the commencement exercises, the stately formality of the caps and gowns, the owl-like gravity with which the new-made A. B. shifts his tassel from the right side of his mortar-board to a position just over the left eye the minute he gets his sheepskin in his hand. He is no longer a boy — he is become a man. The president has just pronounced him to be a bachelor of arts, with all the elusive privileges, immunities and honors incident to that degree. Good old Dr. Eliot used to welcome the boys "to the fellowship of educated men" I remember — and I liked the phrase. The graduating class would not dream of hanging its tassel over its left eye until the parchments had been delivered — but thereafter it would not dream of wearing them in any other position.

I like the bored way in which the president sits down all through the ceremony, merely announcing from his throne that Mr. Smith will now address the assembly on the Importance of the Classics in a Commercial Education (with valedictory rank), and so on. It is only when the president of a college is bestowing honorary degrees that he rises and takes more than a politely detached interest in what is going forward. Making A. B.'s 400 or so at a time is dull work — but making a Litt. D., and two or three LL. D!'s is sterner stuff. The president stands up to that job, just as you and I, brethren, stand up to carve a refractory leg of lamb. Prexy stood up while he made a Litt. D. of Irvin Cobb — and we all wanted to because there was a man who really got what was coming to him.

But the main thing at a reunion is the class — the seeing of men half-forgotten but suddenly recalled. Now and then there's one you can't put a name to at once — changed in body, or in beard, maybe. Somebody you knew but casually even in college. Now who the devil is it? He extends a cordial paw, and as you give him the up and down he grins with delight at your mystification. "Can it be — yes, by Godfrey, it s Stuffy! Why you rascally boob, I'd never have known you in a million years! Where have you been? How long since you've been back? What've you got for a family? God bless your soul. Stuff, I'm beginning to be glad I came!"

Now there's no very real gratification in all this. You'd 'wholly forgotten there was such a man as Stuffy and you didn't have anything much to do with him 25 years ago. To all intents and purposes he didn't exist for you five minutes back — and here you are hugging him and actually feeling a pleasure unimaginable just because he s swum back into your ken after 25 yearsspent by him as you discover in teaching at small pay in a remote western town. But he's back bringing with him one wife and two flaxen-haired girls, distinctly selfconscious and awkward. And you are genuinely glad to see him, because he was one of the old crowd, and because he's back at last for the first time since graduation and because now you think of it he was a good scout. anyhow ! Good old Stuffy!

The lure of the reunion attracts men from afar. Jimmy came from San Francisco. Ajax came from lowa. Decker from Omaha. Old Gib — blind from birth, but of a courage as indomitable as the sweetness of his character — came all the way from Mississippi in a Ford, driven by his soldier son. The people who stay away from such gatherings are usually of two classes — those who live almost in the next town, so that they're never out of touch with the gang, and those who are such incurable snobs that they haven't any bowels of good fellowship anyhow. Every class has one or two of the latter — witness Harper's Magazine this month. Every class has a dozen or two of the former. But if a man lives in Honolulu, or under Pike's Peak, or in the Everglades, Old Siwash will get him once in five years if he has to pawn the tractor or sell the mule.

We have a cup to be won at Com mencement by the class sending back the largest percentage of its living graduates. It was presented by our own class. We never by any chance win that cup. Usually it goes to some aged class that has 18 men living and gets back 17 of them — while we trail along with only about 75 per cent, of our 83 extant survivors. But who cares? Getting the cup once in a lifetime is a little thing compared with a steady record, like ours, for calling back 75 per cent, regularly every time we come — and often more. I suspect we shall only win that cup when we get down to a dozen men or so and manage to round up every mother s son of the dozen. Meantime we set the pace whatever you say. We gave the cup — and we make a good honest try to win it every time, which gives us a crowd even if it doesn't land the cup. And when you sit around the banquet board on a hot summer night, everybody in shirt-waist attire, eating extremely meagre food but rejoicing in the goodly fellowship, you probably say "What about cups, anyhow! This is what we came here for! To see the men we never see at any other time — to sing, with old Nunc at the keys — to listen to the old stories that we never get tired of."

Tim was to have been toastmaster at that dinner; but when we first got to headquarters there was bad news. Tim had telegraphed that the doctor had him in bed and forbade his going. So we gave him up. And yet, just as we paraded with the alumni into the ball park to see the team trim Cornell on the afternoon before the dinner, there was a thin piping voice heard coming from a wayside Ford. It was Tim. That little red-headed runt had escaped from his physician., travelled '200 miles by train, hired a Ford down at the June., and was on hand with the rest of us. He couldn't go to the dinner — he was still too sick for that. But he came — and he counted one vote on that cup which was part of his incentive. The rest was just a plain hunger to see the old crowd. That's the lure of the reunion at its strongest. I think Tim made the longest journey for all Jimmy's three thousand miles from the Pacific coast. He made it for just the same reason — a hunger for the sight of the eyes, which we are told is better than the wandering of the desire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT, 1919

July 1919 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

July 1919 By KENNETH BEAL -

Article

ArticleREPORT OF THE TRUSTEES MEETING

July 1919 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE: RETROSPECT AND OUTLOOK

July 1919 By Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleThe program for the forthcoming

July 1919 -

Books

BooksPUBLICATIONS

July 1919 By W. H. WOOD

Article

-

Article

ArticleOFFICERS IN CHARGE OF THE MILITARY WORK AT DARTMOUTH

November 1918 -

Article

ArticleOVER 8000 VOLUMES ADDED TO COLLECTIONS IN LIBRARY

December 1921 -

Article

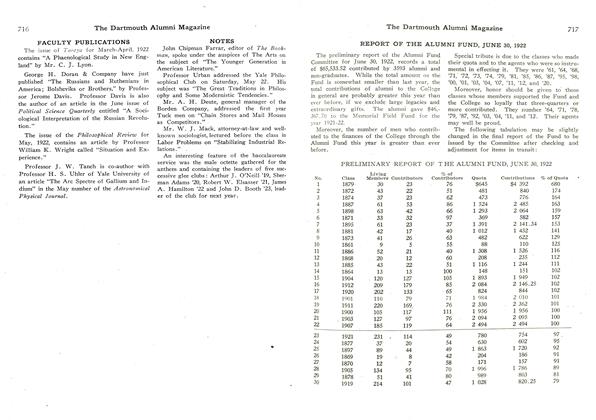

ArticleREPORT OF THE ALUMNI FUND, JUNE 30, 1922

August, 1922 -

Article

ArticleBank President

February 1947 -

Article

ArticleDorms become official

APRIL • 1987 -

Article

ArticleSpotted Record

April 1952 By C. E. W