It is now nearly 25 years since New Hampshire's great jurist ended a long career of distinguished and useful service. The change of perspective which time brings about makes a viewpoint which differs from that of one's contemporaries. This is particularly true of Judge Doe, who was a difficult man to understand by those who enjoyed acquaintance and association with him, and whose memory and traditions are therefore additionally obscured by the indefinite and inconclusive judgment of his own generation. I can only trust that those yet surviving of the ones who knew him will be lenient in their criticism for the short-comings and incompleteness of this article in view of the limitations of the records both written and unwritten concerning him. The value of his work, however, is more readily appreciated and measured, and this is his great legacy, not alone to his profession but to all who have occasion to seek justice through the courts. The history of the law will give him place in the company of those to whom its development is chiefly due and his reputation will be enhanced by that process of time which gives a man his true rank and measure. He himself once said that a man is soon forgotten after he is dead, and that it is only what he does worth while that is remembered and endures.

In brief chronology, Judge Doe was born April 11, 1830, at Derry, New Hampshire, was graduated from Dartmouth in 1849 with Phi Beta Kappa rank, was admitted to practice as an attorney in 1852, was appointed a member of New Hampshire's court of last resort in 1859, and continued in such capacity until his death on March 9, 1896, with an interlude of two years or so before his appointment as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1876. For most of his life his homt [missing text] town of Rollinsford. In religion [missing text] is understood to have been a Unitarian. In polities he was a Democrat until the threat of secession by the South appeared serious to him when he became a Republican, remaining such until his death with all the loyalty and regularity which those of the old line type make the acid test of true faith.

From his early manhood Judge Doe appears to have been of serious purpose, thinking deeply and reasoning clearly. His graduation from college at the age of 19 and elevation to the bench 10 years later indicate a very early maturity of intellectual powers. He called his college days the easiest of his life. Whether this meant a ready absorption of learning and knowledge rather than a neglect of work except to the extent necessary for "getting by" is not easy to determine. He had an untold capacity for work which developed as time went on to the exclusion of relaxation and recreation except such as he took to keep his health good. His energy was tireless and his habits of thoroughness, persistent application and exhaustive research made possible the great amount of work which he undertook and carried to successful accomplishment. Any jealousy of the law towards him was misdirected and misspent, for he had no other pursuits or even inclinations. The law was his life.

He thus became in modern parlance a specialist. He was also a reformer. And in these two aspects may be found the keynote of his career and achievements.

As a reformer he is to be classed not in the type seeking change for the sake of change but with those who seek change for the sake of making things better. He once said the new is good only when it is needed. Dr. Tucker in his recent book "My Generation" calls attention to the movement of the last half of the last century "for intellectual and social progress, and Judge Doe may well be said to have become identified with it in the departments of jurisprudence and legal reform.

In connection with his character as a reformer, Judge Doe appears to have formed a plan and scheme of life based on simple necessities, of "plain living and high thinking" and forerunning Father Wagner's philosophy. He escaped what Emerson has called the frequent misfortune of men of genius to love luxury. On the contrary. This scheme of life he not only applied to himself but carried into his home and family. An organic heart trouble made it necessary for him to conform to a careful and strict routine and habits, and this dovetails in with his philosophy to explain much which gained for him the reputation of being eccentric. If one may judge from his published pictures, perhaps there was further reason for this reputation, his appearance being in keeping with his standard of living. He might well be taken for a Presbyterian Covenanter, or a Puritan stranded two or three centuries behind his time. If frivolity could smile at him, it could not talk with him. He made a non-observance of outward social conventions which conflicted with his views of direct simplicity, and style, fashion and ceremony early abandoned effort to claim him for their own. The practical side of life dominated him and the esthetic side seems to have made but little appeal to him. Also he was apparently deaf to comment and insensitive to criticism, unless well-founded, when he would make ready response, being ever open and fair minded to reasonable argument. This departure from the ordinary was not so as to be unusual and peculiar but was followed as the sensible and practical course to take, and it is for the student of sociology to say how far one is really eccentric merely because his ways in outward appearance and dislike of formalities and "idle ceremonies" differ from those of men in general.

As examples of this disregard of conventional standards, he would use a shawl to keep his feet and legs warm when presiding in court, his shoes were made from unique patterns, he would sometimes try a case sitting with the lawyers instead of on the bench, he would not read fiction, only consenting on one occasion to read marked passages in "Les Miserables" relating to the Battle of Waterloo, in which he was interested, he would take a recess when holding court to enjoy to the fullness of hearty laughter a humorous thought occurring to him, he would refuse .observance of normal ceremony and display and his only known recommendation of a set form was a prayer whose brevity led him to say it should be adopted as a model. When as a judge he rebuked one of the older lawyers who had resented one of his rulings and at whose home he was accustomed to take his dinner whenever convenience permitted, the lawyer's refusal to have further social relations with him did not deter him from following his practice, with the result that the lawyer became one of his greatest admirers.

When Senator Chandler libelled the Supreme Court at a time when Judge Doe was its Chief Justice, the Judge at once wrote the Senator asking him to buy a certain book for him at some bookstore in New York City the next time the Senator stopped over there on his way home from Washington. The libel thus ignored became a dead issue.

When Almy, who committed a most brutal murder at Hanover, was tried at Plymouth, it was in the winter at a time of intense cold. Judge Doe had the windows opened wide for the sake of fresh air much to the discomfort of the audience. This has been cited as an illustration of his eccentricity, but a better explanation seems to be that he was 10 or 20 years ahead of the medical profession in its advocacy of fresh air as an essential for health. In the same way many would regard him as & generation ahead of his time in his remark that after giving much study, to the Irish people and the Irish question, he had reached the conclusion that they and it were incapable of solution.

Judge Doe enjoyed conversation of interest. He liked to listen and on being asked questions was a good talker. He had a profound sense of humor, which doubtless went far to keep him cheerful and in good spirits and without which he would have been the same inwardly as he appeared outwardly, dour and somber. His mental alertness brought this humor into play continually and did much to reconcile his rigid philosophy with the brighter and lighter attitude of life.

It has been said of him, but denied by Judge Jeremiah Smith, that he failed to receive an appointment to the United States Supreme Court on account of his opinion in the "Mink" case (Aldrich v. Wright, 53 N. H., 398), which is one of the ablest expositions of the constitutional right to protect and defend one's property ever written. While there is a satirical humor in a few of the 25 pages of the opinion devoted to the proposition that if it appears the right thing to do, one may protect his geese from attack by mink by shooting the mink without first driving away the geese or driving off the mink. Yet the opinion is a serious consideration of an important doctrine. It was never Judge Doe's way to make light of serious matters and for him cases involving but small amounts—in this one it was $40—were of no less consequence than those in which much was at stake. His facility of expression and force of academic reasoning will explain his satire much better than any charge of insincerity which was alien to his nature and incapable of being naturalized, and particularly in his work. The case will long endure as a valuable precedent and that is the real test, rather than the relief it gives to the tired law student whose mind finds comfort in it as in an oasis in a region which is apt to seem generally dry to him.

In 1642 one of the high courts of England defeated a suit for 1000 pounds, or at least prevented its further maintenance, because the plaintiff in his pleadings said that a certain party was dead instead of saying that he was not living. I do not know that Judge Doe ever ran across this.decision. If he did, it merely added to his impatience for any rules or procedure that tended to accomplish injustice rather than promote justice, and wherever he found them, he treated them with energetic opposition. Technicalities were a red flag to him and indirection found no comfort when he was at hand. Practices that made for delay or denial of the merits and equity of a cause were handled by him without gloves and given high handed treatment.

At the same time no one had greater respect for precedent and authority for principles of substantive law. The covenant of the government with the people of England in 1214 that justice should not be sold, denied or delayed was ever in his mind and he gave it a liberal construction so that justice according to law and in a real sense should not be denied or delayed. By this organic expression of the law he guided his way in his work of legal reform. Adhering to it and to all the developed body of substantive law, he was at all times conservative and never radical. It was only towards customs and practices that subverted this law or interfered with its continued progress that he directed his attack. His respect, even reverence, for authority, for the constitutions which we have ordained and for the established institutions of government was unmeasured and unlimited. He would cite precedent after precedent to support his position and all his contests were in a broad and true sense to save and keep the law rather than to change it, and to make it useful in promoting practical justice rather than to let it be made to serve ends . which defeated its purpose.

In this same line and in conformity with his plain simplicity, he sought to make procedure efficient so that parties would not suffer the expense of difficulty and delay in obtaining a "fair trial" of the substantial trouble between them. He was a friend of the "ordinary man" and his sense of fairness and justice was ever awake and alert to see that parties had what has later been characterized as a square deal. He would let mistakes be corrected promptly and often in an impromptu manner and would cut short efforts to make mistakes of serious import. To use his own language taken from some of his opinions: "The question of form of action is not considered when it is of no practical consequence and time spent on it would be wasted." "By a principle of our common law for ascertaining, establishing and vindicating legal rights, such procedure is to be invented and used as justice and convenience require." "It is a general rule of the common law of rights that a right is entitled to an adequate remedy for its infringement and to the use of convenient apparatus of procedure for ascertaining and establishing the right and obtaining the remedy." The older lawyers objected vigorously but helplessly to his course and many of the younger ones failed to appreciate the credit due him for making it easy instead of hard to have a case tried on its merits.

In constitutional law and in the law of evidence judge Doe perhaps did his best work and wrote his most valuable and important opinions. Prof. Wigmore's treatise on Evidence is dedicated in part "to the public services and the private friendship" of Judge Doe as a "master in the law of evidence." In his opinions on constitutional questions he always exhibited breadth of view and gave a sane and reasonable construction after going into exhaustive research for anything and everything having any possible bearing.

A summary of his standing has been well stated in the following tribute: "Judge Doe was the ablest Chief Justice New Hampshire ever had. He held the position for nearly 20 years, and during that time, and a prior term as Associate Justice, he wrote more opinions than any man who has sat upon the bench in this State. This work is characterized by great learning, careful research and a most extraordinary grasp of legal principles. Common law forms and technicalities were not regarded by him, and as a reformer of legal procedure, he has left an enduring mark upon the jurisprudence of New Hampshire. He is entitled to a place in the first rank of American jurists."

In his opinions Judge Doe was at times laconic and at times voluminous, so that his work almost seemed "to pour forth in profuse strains of unpremediated art." Yet such an inference is wholly erroneous, for his force and clarity of expression always attested careful and exhaustive labor of preparation. It has been said that some of his extended opinions were written to convince his associates that they were wrong when they disagreed with him and if this is so they appear usually to have had the desired result, as recorded dissent is infrequent in the reports which cover the period of his work. His laconic method is best shown in his invariable signature of four letters, "C. Doe," and from literary standpoints as well as practically the reasons for the result were often as clear, and certainly, as effective, as when the more discursive method was used. He had a habit of what has been called a double and inverted negative to make his assertions positive. There is a deleted sentence from his opinion that a woman might practice as an attorney if otherwise qualified which runs as follows: "Who will be bold enough to say now that in a hundred years hence it will not be true that English courts will not be as much surprised to see a lawyer appear dressed as a lady as they would be now to see him appear dressed as a gentleman." He was always clear, direct and forceful in expression. In one opinion he has described the fine print in an insurance policy as being "in the typographic style commonly used for the suppression of information." And when he wrote: "the law does not wantonly destroy the right which its promise has drawn into its judicial possession, and it has no occasion to adopt any other than a straightforward mode of announcing and recording the date and effect of its judgment," he reflected the direct and logical course in which his mind worked,

It would be an incomplete statement of Judge Doe's services as a judge to refer only to his opinions. With plain sense, practical judgment, direct methods, a fund of humor, and application to work, he despatched the business of the court with high executive ability and meeting efficiency's test of seasonable and correct results. It has been said that his discussion in conference with his associates are among the lost treasures of the law.

Judge Doe's reputation as an eminent jurist will survive so long as a government of law survives. His work in promoting real and substantial justice through legal tribunals is his great memoral, and in the achievements, the service and the virtues that were his is his dedication to the greater glory of the law.

Note—The writer acknowledges as sources of information about Judge Doe the records of the proceedings of the New Hampshire Bar Association at the time of his death, the address of Judge Jeremiah Smith in 1897, the address of Judge Robert G. Pike in 1916, and as furnished by Mr. Thomas D. Luce of Nashua, N. H.

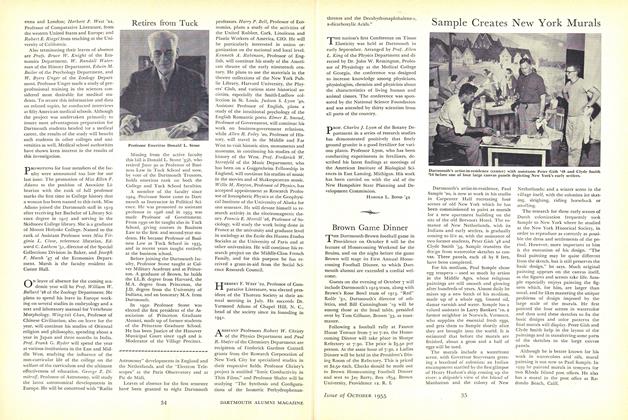

CHARLES DOE 1849 Reproduced from a steel engraving in possession of Elmer E. Doe, Esq., son of Judge Doe

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA REPORT TO THE ALUMNI

March 1921 By JAMES P. RICHARDSON -

Article

ArticleThat breeziness of the boreal climate

March 1921 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

March 1921 -

Article

ArticleWEBSTER LETTER PROPHESIED TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH

March 1921 -

Books

BooksPUBLICATIONS

March 1921 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH LIFE IN 1820

March 1921 By JOHN GROSVENOR DANA '22