PRESIDENT CONTRIBUTES EDITORIAL TO "THE PUBLIC LEDGER"

December, 1922 ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS.The following article, published in the Philadelphia "Public Ledger," is one of a series which President Ernest Martin Hopkins has written to elaborate on some of the points which he made in his address to the undergraduate body at the opening of the college year:

One of the greatest weaknesses of democracy is the taste for palatable untruths rather than for more nourishing but less agreeable facts. Nowhere is this more true than in the problems of education, a condition which needs to be recognized at the present time, when these problems are seemingly of greater interest and of more intimate concern to people of our country than ever before. Evidence of such interest is afforded, on the one hand, in the greatly increased numbers seeking enrollment within our colleges, while, on the other hand, it is significant, that any statement of theory or practice affecting the policies 6i the colleges immediately becomes a focus for public attention and animated discussion.

It is highly desirable in our thinking upon these matters to be sure that we are ascribing like meanings to like terms; otherwise the hope of securing any common understanding of what the issue is, to say nothing of arriving at a common conclusion, will be made wholly impossible. For instance, if one makes the statement that membership within a college is a privilege and not a right, he does not say that opportunity for education should be denied to any man. The statement simply suggests, that varying kinds and varying amounts of education are due to varying groups, according to their respective abilities to absorb benefit. It would seem to be fairly obvious that there is no advantage to anybody in utilizing the college process for a man who cannot or will not benefit by it, to the impairment of its effectiveness for all those men who are capable of deriving advantage from it to become more serviceable citizens.

It is well to bear in mind that we have to face a condition and not a theory at this point. There are not enough colleges to enroll the men who wish to be admitted and to maintain work of the grade which could be maintained with the lesser numbers. Nor are the resources now securable to make this possible. The question then becomes: "Will society conceivably be more benefited by a policy of cheapening the whole proposition than by raising the standard of achievement and accepting only such men within the colleges as can best utilize the opportunities which are there offered?"

Moreover, even assuming a greater effectiveness on the part of colleges than they have ever claimed or than they have ever been able to demonstrate, it would still be true that the terms "college course" and "higher education" are not synonymous. It would be a great blessing to society if all holders of a college degree were actually possessed of a genuine education. It would, on the other hand, be a great misfortune to mankind if the content and mental discipline of higher education were exclusively to be found in men who had been afforded opportunity to subject themselves to the college process. Fortunately for the world, there are many different ways of acquiring learning and culture, and throughout all time men and women have so acquired these. A formal institution of learning is only one of the several methods, and not for all men the best method.

Some find their approach to the intellectual equivalent of higher learning over the rocky road of practical experience and through grasping for and utilizing to the full all opportunities for self-improvement, while others possess themselves of it through the quiet seclusion and reflection and in purposeful reading and study. The real argument to be advanced for the college is that through its many facilities and its various advantages higher education can, for most men, be more easily and more quickly acquired in it than by any other procedure. But this very fact might be detrimental to the occasional man who, in the sterner and more rigorous course necessary for self-development, does cultivate a stamina and an initiative that the college might never have instigated in him.

It behooves any college officer to emphasize this point again and again lest the men who go out from under the college influence either lack the essential grace of humility or fail to render the homage due to those men of ambition and persistence who, in the face of all difficulties, have accomplished what other men barely have accomplished with every form of assistance and encouragement made available to them.

In short, that which we call higher education is not to be considered as withheld from a man if he is denied the opportunity of a college course whether because of his own inability to seek it or because of the college inability to enroll him, or even if under other circumstances, he is denied continued membership within the college because of his inability to utilize its method advantageously.

The alternative process is, to be sure, fraught with greater difficulties; but to some men, at least, it is better adapted. Only a small proportion, perhaps, qualify on this basis, but the actual numbers are not small. The college is a useful and doubtless an indispensable agency for developing and perpetuating the ideals of learning and culture among men, but it is not the only agency.

In order that the college may not be held accountable for that which it is not humanly or spiritually possible for it to do, let us not load it with the responsibility of meeting a dictum pleasant to the ear but without foundation in fact—that the college owes it to the idea of democracy to accept all men as candidates for its specialized form of education, regardless, of their intellectual aptitudes. Let us not allow the argument to stand that in restricting its efforts within selected groups, who can most advantageously utilize it, the college is making higher education impossible to those who are entitled to it and is condemning vast numbers of those who are capable and ambitions to ignorance and hopeless social handicap.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTEACHING SCHOOL

December 1922 By EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleNEWSPAPERS CONTINUE DISCUSSION OF PRESIDENT'S ADDRESS

December 1922 -

Sports

SportsFOOTBALL

December 1922 -

Article

ArticleIt would be too much to expect Dartmouth's new system

December 1922 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

December 1922 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1919

December 1922 By John H. Chipman

ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS.

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEN IN PALESTINE RED CROSS EXPEDITION

May 1918 -

Article

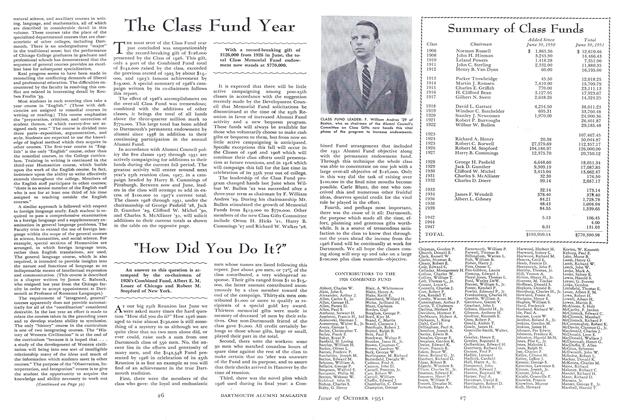

ArticleThe Class Fund Year

October 1951 -

Article

ArticleGreen Jottings

October 1961 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleHarvard 17, Dartmouth 13

DECEMBER 1963 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleExecutive Support

APRIL 1991 By Fred Carleton '53 -

Article

Article1911*

May 1939 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH