by this time some facts as to the uses made of spare time by undergraduates. It has been known that an investigation was going on, some 200 students being requested to keep diaries and turn them in for inspection in order to learn what was the average custom of the student body in its hours of ease. Of course this investigation does not in any sense savor of puritanical espionage—which it might have done forty years ago if the same expedient had been suggested then. It represents solely a scientific desire to ascertain the facts as to the present diversions of the student body, with a view to learning more about the non-academic side of student life that officers of instruction are likely to know by the processes of casual observation and occasional hear-say.

This is not the place to comment on the actual revelations, which is a task better suited to those who have read the various diaries and collated the results for use in other departments of this and other publications. Our present desire is to consider the activities open to the modern undergraduate and perhaps to estimate the worth of some as transcending that of others. An alumnus of more than twenty-five years' standing runs some little risk in such a matter because of possible failures to appreciate how greatly the college has changed since he was young and was a student himself. That it has changed most notably of all in its social life is not a rash statement. When one harks back to the comparatively dark ages in which the one festal occasion was Commencement week — at which time alone female beauty invaded Hanover — it is astounding to note the altered circumstances produced by frequent house parties, winter carnivals, junior proms,'"and such like events. The days of monastic simplicity are gone. Winter, which once operated like stone walls to make a prison for the cloistered undergraduate, now appears to be the very hey-day of the social season.

The appropriate place of such events in the scheme of undergraduate things we propose to consider in more detail in a moment. For the present, what of undergraduate life when there is no house party — when there are no young women of one's acquaintance in town, and when the student is thrown back upon the jocund society of his fellows for such diversion as the winter environment permits ?

Not even a professor supposes that young men in circumstances like these will spend all their hours out of classrooms in the ardent pursuit of learning, beyond what may be absolutely necessary to prepare for a reasonably creditable appearance next day. It is quite probable that professors now, as of yore, expect rather more of this than is actually delivered. It certainly was true in the days with which the present writers were personally familiar. One used to be soberly informed that no student could prepare himself properly for the tasks of the next day without spending at least two hours in concentrated study on each subject about to be recited upon, or lectured about; indeed the suggestion of this irreducible minimum was generally made in a tone indicative of a belief in the faculty mind that the student should consider this getting off lightly enough. But even so there remains a fair surplus of time for students of nocturnal habit, who might conscientiously put in the specified two hours on political economy (as it used to be called), two hours on psychology, and two hours on the history of philosophy.

In those days the winter was a season of indoor activity far more than it is at present. We recall one professor whose earnest advice was to pile high the fire, seal the windows and doors hermetically, and above all not to leave open the windows at night during the period of sleep. "Nox — noxious" was his sententious Summing up the evils of breathing the free air after dark. Like other professorial advice, this was not invariably followed ; but the usual pastimes for the 400 or so of Dartmouth men in those days were certainly not those of the toboggan chute, the skating field, or the ski jump. The most one saw of the keen outer air was apt to be in making hurried transits between one's superheated room and the various goals — chapel, boarding club, recitation hall. Now and then, perhaps, a jaunt in a sleigh to some such gay metropolis as Lebanon would be afforded by pooling the slender financial resources of half a dozen men. But the main excitement was to be found in certain favored rooms, where dwelt notoriously hospitable souls, or at the fraternity quarters which in those remote days were far from palaces of delight.

Card games, mainly innocent but by no means invariably so, occupied a prodigious place, one recalls. In the idle hour or two after what was in those days called "supper" and before anyone felt seriously called upon to approach his studies, there was a very general devotion to whist (as then understood and practiced) or to "Pedro," or other popular games. On Saturday nights one felt free to make an evening of it, followed by an oyster stew party at "Lill" Carter's. One dismisses from the discussion the more sophisticated diversions of the sporting element — never very large in that day. We speak here of the average bourgeois, ill provisioned with wealth and forced to fall back on the simple pleasures of Hanover as it was then.

One looks back with some amusement and with some regret, for it is easy to see at fifty how many advantages one ignored at twenty-two. We did read more or less for pleasure — and if a well-thumbed copy of Boccaccio or Rabelais found its way now and again into select circles, was any one much the worse for it? But one didn't read nearly enough. One did play cards rather too much. And on the whole it was a not unwholesome sort of life, possibly too much beset by unproductive idleness, but certainly not heavily tinctured with the criminal. The suspicion is that the student of between twenty and twenty-five is pretty much the same sort of animal in all ages, given to pranks, to pastimes which he will later himself admit to have been distinctly barren from the maturer point of view, but nevertheless food convenient for him at that stage of his development and probably not such a waste of time as his elders then, and himself later, might naturally assume.

Relaxations have their highly important place — and relaxations are pretty sure to be devoid of intense intellectual application. They have become much more numerous and much more diversified than they were in days anterior to the development of radio and the cinema. That they are more wholesome is on the whole probable — as a net matter, at all events. The greater sophistication of the student population argues little either way. There is certainly less of a tendency to make evening pastimes a matter of little groups in stuffy rooms. But, as always, one fears there is a much lower estimate set upon the reading of books than would be pleasant to findmore zest for livelier excitations, as is apparently natural among men of that age, who find in "this freedom" something rather intoxicating and exhilarating.

An assemblage of some 2000 normal young men, free from bothersome oversight and fascinated by the opportunities to spend their free time as they choose, will probably reveal itself as much the same sort of a congeries anywhere. In a remote locality, such as Hanover, where the privilege of running into a large city for the evening, is withheld, such a body has to be self-sufficient - and it is so. One may therefore read with lively interest the record of what at this highly developed day the student body regards as the favored methods of spending idle time, ,and may contrast it with what was the most favored custom a generation or two ago. For a guess, the conditions are much improved and the use made of them somewhat improved also — although one with the rooted faith that human nature alters not with the brief hours and weeks is prone to say that the young of the human species will conduct themselves in about the same general ways in 1923 that they did in 1889.

Mention was made above of the greatly enlarged social life, due to the more frequent incursion of sisters and sweethearts. The result is a multiplication of divertisements in ways wholly unknown to the fathers of men now in college. A "ball" at Commencement was the only society function of a general nature at Hanover — plus one or two private parties in the same week. For feminine society the daughters of a small but prolific faculty were relied upon, plus the sometimes difficult and very moderately expensive journeys to Lebanon, where those inclined toward Terpsichorean agility might find a semi-occasional opportunity to gratify the natural craving for feminine society of sorts. But when the fraternities began to have spacious homes of their own, and when young men began to frequent Hanover who boasted evening clothes even in freshman year, a change stole over the landscape which the grandsires of the present student body would hardly have considered possible. Beyond doubt the incidents of student life cost much more than they did in the days of our simplicity. Where the student of 30 years ago felt himself empowered to invite the girl of his choice to visit Hanover with appropriate chaperonage at his Commencement, it now appears to be quite the usual thing to invite such with frequency, to participate in the gaieties of mid-term. And it is a good thing, too, provided it can be reasonably afforded. There wasn't nearly enough of it in the old days. All of which, of course, with the subliminal qualifications that it is susceptible to rampant overdoing, both on the score of frequency and cost.

Those who incline to question the place which house parties and carnivals and winter promenades have come to occupy in the undergraduate economy, must remember that it is the current way of the world — precisely as in former days other things were the way of the then world — and that what young men do now is bound to be criticized by their sedate elders in exactly the way that the latters' fathers, were wont to criticize. As usual each side of such a controversy is about half right and half wrong — and equally as usual, youth will be served. Social activities are unquestionably overdone in many cases, and one imagines that if it were left to the old-timers to decide they might be underdone. But it is pleasant to feel that in spite of the altered circumstances, the greater sophistication, the multiplicity of social airs and graces, the enlarged opportunities and the greatly augmented costs of "getting an education," it cannot be said that there has been any failure to set a watch lest the old traditions fail.

Interesting echoes of the idea advanced by President Hopkins in his now famous opening address at the start of the current college year, in which reference was made to "an aristocracy of brains" and to "too many men going to college," continue to be heard. One of the most notable was the elaboration of much the same idea as that expressed by the president of Dartmouth in an address to the alumni of Brown by President Faunce, speaking at a midwinter dinner in Boston. Dr. Faunce intimated that the proper aim for colleges at present was to improve, the quality rather than increase the quantity of students, adding that some men are better off without a college course and should not cumber the path of others who would be better off if they could obtain a college education.

This is clearly an adoption of the same general view given out by our own president at the opening of the first semester, but in language less likely to be misinterpreted. It is agreeable to find the theory endorsed by so experienced and so competent an educator as President Faunce. One believes,, however, that Dr. Hopkins performed a distinct service when he voiced his theory in the more daring formula, because it sufficed in that guise to arrest and focus public attention, where otherwise it would doubtless have passed as mere commonplace. It enables other educators, taking much the same line of thought, to get a hearing which they might not otherwise obtain — and that in turn strengthens the contention which Dr. Hopkins originally made.

Speaking before a women's organization in Boston, President Meiklejohn of Amherst reiterated his belief that the overdoing of college athletics should be stopped and hinted that among the ways of curtailing extravagance might be the reduction of admission charges to football games. The revenues derived from the brief, but lucrative, football season apparently seem to Dr. Meiklejohn to tempt student organizations to a more lavish expenditure than could be countenanced if the revenues were less in magnitude. He would also discontinue the system of paid coaches for the various teams.

While admitting the justice of the criticism habitually levelled at the grossly exaggerated cost and the overrated importance of athletics in the academic field, we entertain the gravest doubts of the entire feasibility of this new proposition — especially that of abolishing the coaching system. That this tends to be overdone is likely enough; but that it has the slightest chance of being done away with the acquiescence of students and alumni seems to us impossible to believe. There is also doubt that merely reducing the available revenues will cure the evil, or even minimize it, while so many feverishly interested alumni stand ready to finance athletic victories as the one thing in life that matters. In this regard every college has hundreds of alumni who are as fervently interested as the sophomore class — and these would infallibly resent any very sweeping changes in spite of every logical argument. One must take men as they arerather than attempt to act as if men were what some of us may think they ought to be.

To recur for a moment more to the address of President Faunce before the Brown alumni at Boston, it is interesting to note his endorsement of another doctrine which has had more or less said about it this winter — to wit, the doctrine of alumni participation in college government. He apparently accepts the view (which we fully share) that the contributions of alumni to collegiate management may be spiritual as well as monetary, and that the dangers of an excessive domination are being exaggerated by such as would have the alumni ignore the tasks of management altogether in favor of mere social reunions and willing outpourings of cash. These confirmatory sentiments tend to cement convictions already expressed in these columns.

Few intercollegiate victories could bring such satisfaction as that derived from the results of the recent Intercollegiate Glee Club contest in New York. As the concert was broadcast throughout the country doubtless many Dartmouth men had the satisfaction of listening in while comfortably at home.

Of late years the College has been able to hear some of the world's leading artists in the musical field and the capacity audiences in Webster Hall have indicated due appreciation, but we have never gained a reputation as a singing college. This victory is therefore all the more welcome, won as it was in the keenest competition.

The untiring efforts of Professor McWhood, director of the Glee Club, have done more than anything else to place the Glee Club in its present enviable position and to stimulate the musical interest of the College. It is an achievement in which we may all feel the greatest gratification.

BARTLETT HALL : now used by the departments of Psycho logy and Education and containing the Associate Dean's offices

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleRAMBLING THOUGHTS OF A CLASS SECRETARY

May 1923 -

Article

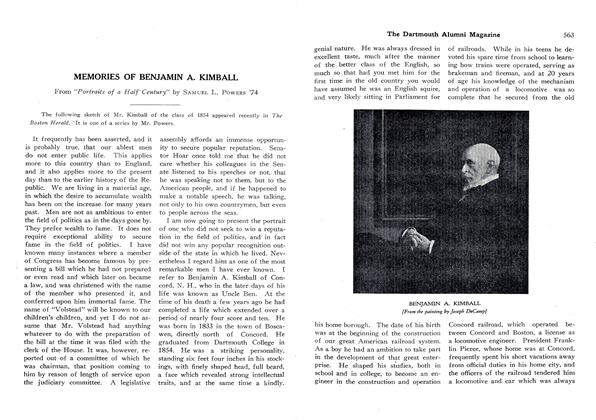

ArticleMEMORIES OF BENJAMIN A. KIMBALL

May 1923 By SAMUEL L. POWERS '74 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

May 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1919

May 1923 By John H. Chipman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

May 1923 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Books

BooksSidelights on American Literature

May 1923

Article

-

Article

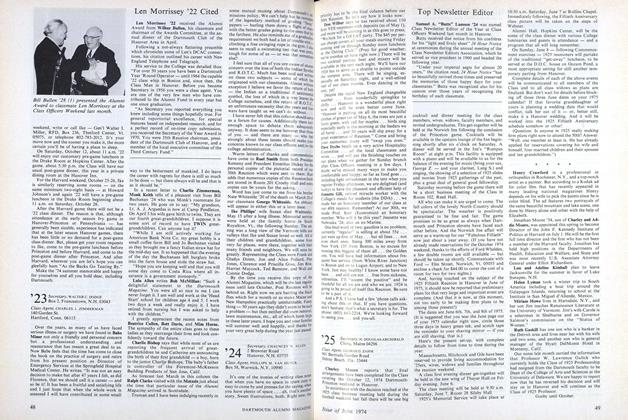

ArticleLen Morrissey '22 Cited

June 1974 -

Article

ArticleAn Honor for the Editor

December 1989 By Carl L.N. Erdman '37 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

June 1954 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Renews Its Bonds with England

JULY 1973 By JOAN HIER -

Article

ArticleCongratulations

January 1935 By The Editors -

Article

ArticleThe Dean's Shiny Nose

November 1956 By WILLIAM R. LANSBERG '38