I received the courteous invitation to address this meeting of the National Collegiate Athletic Association in the late weeks of the summer. I accepted with appreciation of the opportunity offered. At that time, I expected to confine myself to a discusssion. of those decreasing, but still existing, faults which here or there pertain to the affairs of intercollegiate athletics,—faults which sometimes work contrary to the aspirations of the American college to develop an intelligent manhood, upright in its personal characteristics and honest and generous in relations with its fellows

I have in no wise changed my belief that attention to such faults is a continuous responsibility for all men interested in colleges or in intercollegiate athletics. The more pervasive the influence of athletics may become, the more serious are any defects which may attach to this activity.

oping desirable human ideals, and their influence in illustrating in actual practice the merits of certain principles which at most the college curriculum can simply state. So rapidly has the situation changed within the last few weeks, however, and so largely has skepticism been aroused in regard to the spirit which pervades the institution of intercollegiate athletics, that emphasis needs to be placed at another point in public pronouncements at this time. For the moment it seems to me to be more important to suggest considation of the fact that intercollegiate, athletics have their major recommendations, their elements of effectiveness in developing

I have in no wise abandoned my belief that intelligent treatment should be given for those minor ills which afflict the patient, I would, however, very strongly argue that the patient be placed under the ministrations of those who seek his health rather than those whose convictions lead them to desire his demise.

For common understanding, please realize that in discussing the subject, "The Place of Athletics in an Educational Program," I am thinking of intercollegiate athletics, and largely football, and that I am thinking of these in terms of the American college. Consequently, in view of the turn of events more recently my words will have to do mainly with the question of the place of intercollegiate athletics in the American college.

As I embark upon the hazardous sea of pronouncement of belief in regard to this highly controversial subject, I wish to make one statement for the, many men who will not agree with me. My course has not been marked in ignorance of the storm signals flying at all points, but rather has been prescribed by these. The standards of intercollegiate athletics are higher at the present time than ever before, and conditions within are cleaner. In this matter, as in other major affairs, ultimate advantage, I believe, cannot so definitely be expected from revolution as from a policy of gradual evolution.

In the ancient Book of Wisdom which we call Ecclesiastes, the preacher-king enunciates a fundamental principle of administration in these words: "To e,verything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven; a timeto break dozvn and a time to build up."

It is then with a deep-seated conviction that vital values lie in intercollegiate athletics which ought to be preserved that I undertake discussion of the subje,ct assigned to me. It is likewise, in definite belief that in connection with this institution the breaking down processes are further advanced than is commonly recognized, that I would call upon the friends of athletics for their immediate and intelligent concern. Let them not fail to recognize abuses, but let them rally to the task of building up understanding of the re,al significance of intercollegiate sports! And let them further rally to the task of making this significance worthy of the deep influence which it exerts.

The breaking down process is naturally always at work among those who hold that the purpose of the American college is solely a scholastic purpose and who believe that the college responsibility is the production of an animated mental process, regardless of any other qualifications. These believe that their conception of a college purpose could be far better achieved if the institution of athletics were non-existent. Furthermore, they believe that the interest now given to athletics would, if these were eliminated, be given by college men to self-development intellectually.

To this permanent group of the opposition has now been added a violent and increasing wave of antagonistic criticism both within and without the colleges, from among many of those heretofore friendly, or at least not hostile, who feel themselves to have been disillusioned. The thinking of those of this group is somewhat along this line: that they had assumed men in college athletics to be men in college primarily for an education and to be incidentally on athletic teams, whereas, on the basis of recent developments they have become convinced that intercollegiate teams are made up of men primarily athletes, accepting the academic discipline merely for the sake of being eligible for competition in college sports and gaining personal glory and renown therefrom. Hereupon they logically ask why, at a time when educational opportunities are too few for those desiring them, taxpayers or private donors should be called upon to support eleemosynary institutions wherein so many of the available places are preempted by men primarily seeking athletic reputations which they may capitalize commercially. Especially, they ask why should this be so whe,n other men, with less muddled conceptions and less distorted perspectives would more profitably and more legitimately utilize the educational facilities which the college offers. Also, many another related question is asked.

These queries must be given consideration. By all means, let us seek to correct defects and to remedy weaknesses. At the same time, if these weaknesses are simply incidental to the general structure of intercollegiate athletics rather than sigsignificant of a general decay, let us strive that virtues shall not be, ignored and that strength shall not be overlooked! Let us, for instance, ask how many, among the tens of thousands participating in athletics in the hundreds of colleges, have given us cause for disappointment or have led us to question the influence of college athletics or the intelligence of these men in estimating relative values.

There is some light, at least, offered at this point in reading a list of the recent elections to Rhodes scholarships for three added years of highly intensive study to be superimposed upon the college course. Among these appear such names as those of George Pfann of Cornell and Nate Parker of Dartmouth, and others of the same kind. There is further illumination in the attitude of Oberlander and his mates on the Dartmouth team of this year, of Tryon at Colgate, and like men or groups on many another team among the hundreds of colleger playing football.

Those victims of professional promotors who sell their academic birthrights for messes of pottage are less to be condemned than commiserated, for to them the time is soon coming when realization will be forced upon them that no easy money will ever pay them for loss of the affectionate regard of their fellows or for loss of the idealizing admiration of the public. These men, however, who constitute but an insignificant percentage of men playing football are not representative of the thinking of college men in general nor indicative of the spirit of intercollegiate athletics in which college men participate. These facts should not be forgotten in investigations which may be undertaken and in reappraisals of the merits of intercollegiate athletics which may be sought.

I hold unreservedly to, the belief that the supreme purpose of the American college is the development of intellectual capacity, the stimulation of mental interest, and the enhancement of the sense of moral and spiritual values among its men. But I have never been able to convince myself that this belief was exclusive of another conviction that admirable as these qualities are in any men, they are particularly admirable and doubly effective in men having capacity for or interest in a wide range of life's activities.

I cannot acquire much interest in the mental dullard nor can I avoid impatience at the man capable of distinctive achievement in matters of the mind who allows himself to be satisfied with mediocrity in scholastic accomplishment or to be complacent with nothing better than passing marks. It is to be emphasized, however, that the majority of men of this type are not the athlete,s nor the doers of anything else in the community life of the college. The great proportion of these men who rank as ineffectives, and almost non-participants, in the curriculum life of the college, are as well non-participants and lacking in interest at every other point where effort is demanded or where accomplishment is expected.

Personally, I have not found the wellbodied, emotionally normal, physically active and sports-loving college man less capable mentally nor less sensitive morally than his fellows who have lacked these attributes.

I have great respect for the scholastic specialist who sacrifices all else to the perfection of final excellence within his chosen field. He is a profitable and oftentimes an indispensable servant of humanity. His contribution to life, nevertheless, almost inevitably and invariably will be that of a specialized staff officer, informed in regard to a single subject, rather than that of a principal upon whom the world's responsibilities may be loaded. The world's work will never be done, nor will understanding of its problems ever be possessed by him in like degree with his brother of intellectual acumen and trained mind, who supplements his mental equipment with a broader outlook upon life's interests and with keener perceptions of the varied colors and shapes constantly appearing in this kaleidoscopic universe. Upon the development of a manhood of this latter type, the enthusiasms, the ideals and the practices of intercollegiate sport are not without a genuine and a desirable influence, the equivalents of which are not available elsewhere in college life.

I admire and respect genuineness, even in behalf of what seem to me, to be mistaken causes. But I abhor the pose of a decadent culture, and dislike the affected sophistications of superficial observations or callow theories of individualism, to which many of the undergraduates in American colleges today seem to be partic- ularly susceptible. To the contagion of the,se attitudes, the ideals and influences of intercollegiate athletics, including, if you will, sometimes hysterical fervors and loyalties, offer the most effective antidotes which are at hand. Until some other antidote as pervasive and as effective can be discovered, and its efficacy proved, I am unwilling to see intercollegiate athletics hamstrung or radically dwarfed in American college life.

I hope that it may be recognized that in dealing with general principles and in considering general attitudes, I am consciously and deliberately omitting the discussion of many a reservation which I have in regard to details of policy or procedure. In the time available for my talk this morning, there is little opportunity for more than categorical statement. Obviously, little opportunity could be offered in a session of this sort for detailed argument or for itemization of data upon the basis of which conclusions have been formed.

At other times I have tried to suggest the implications of the fact that man is not a disembodied intellect and is not likely to become so, that he is influenced by heredity and environment, that he is susceptible to indirect and obscure impulse about which we know little, and that he responds in varying degree to stimuli from within and without of whose origin we know nothing. It is not simply rhetoric when we discuss the function of the American college in terms of the development of manhood.

Never, from the days of college beginnings has it been possible to shut the college life up to an interest solely in matters of instruction and of learning. Youth of earlier times who have sought the colleges have not shunned quarrels, avoided tumults or looked askance at fights. Today they are not freed from the necessities of the give and take in personal relations which are inevitable concomitants of group life. Neither in the remote past nor more recently have they been dehumanized as to appetites or passions, the control of which is the first step in developing true manhood, and a step without which intellectual development is futile. Hence began long ago and has continued to our own time, as it will continue through all time, the development of the; college as a community alongside of and intertwined with its development as an agency for stimulating the mind. Traditionally, the processes are of like age.

If we make this distinction in college life between the educational program and the community, I would be willing to accept the assertion that technically speaking, athletics have no place in the educational program. If the sole function of the college were to maintain an educational program, I should favor the, elimination of athletics. The logic justifying such a statement has already reasonably and desirably led to the abolishing of athletics from the graduate schools of America and from most of the professional schools. Among these, in the large, no responsibility is assumed for anything except the educational program.

Athletics, then, in the field of higher education, is a problem pertaining exclusively to the college and to the undergraduate departments of universities. Our convictions as to the legitimacy of athletics in the college life ought to depend very largely upon the extent to which we believe the college could, if it so de,sired, confine interest exclusively to the curriculum and the extent to which we believe that the American youth would become a better mate for his fellows and a more desirable member of society if this were done,.

I have heard description from many an alumnus of many a different college, of life and conditions in the years before athletics became a feature. Even then, not all available time was given to intellectual pursuits. Seriousness of purpose 'was not universal. Dissipation was not unknown. Conventional behavior was not more refined, and personal courtesy was not more considerate;. In fact, au contraire!

Likewise, my own observation of and information about men in countries where intercollegiate athletics do not prevail in connection with educational institutions have not led me to a conviction that athletics should be lightly dispensed with at home.

On the positive side, there seems to me, first, to be a presumable connection that cannot be lightly disregarded, between athletics and many healthful features of college life today as compared with undergraduate life of earlier days. Secondly, there seems to me, in other things than sport, to be an aptitude for team play and a virility and a sense of desirable sportsmanship in the American college man not so evident in the students of countries where athletics are unknown or undeveloped in connection with institutions of higher learning.

On the negative side, though I were to ascribe to intercollegiate athletics evils greater than any which I believe to inhere in them, I still should wish to know what was proposed to take their place, and something of the likelihood that their place would surely be taken by the suggested substitute if athletics were to be dispensed with.

There is scriptural authority for the fear that a miraculously created void may not be advantageously filled. The evil spirit which returned to the antiseptically swept and garnished chamber, from which it had been cast out, came not alone, but had associated with itself seven other devils; and the latter state was correspondingly worse than the former.

It is not surprising, in a country where we strive to make men temperate by legislation, industrious by court decree, and happy by political oratory, that we, should assume our ability to make men scholars by denying them the opportunity for indulging in any other interest. But arguing from analogy, we lack certainty that this would be the inevitable outcome!

Consequently, arguing either from the one point of view, of an inherent merit resident in athletics, or from the other point of view which holds their influence a lesser evil than many others which might come in to the vacuum they would leave, if they were to be abolished, I hold to the belief that athletics are a legitimate and a salutary interest of college men and therefore that their maintenance and control are a legitimate and a desirable responsibility of college officials.

The American temperament is a competitive, temperament, and at work or at play, it responds best to the spirit of competition. The organization of the American college is not such that a spirit of rivalry in intramural sports or in interclass competitions can be aroused sufficiently to be of major consequence. Because athletics on a scale to interest any considerable number of men require the final incentive of intercollegiate contests as a goal, I believe, as for other reasons, in intercollegiate athletics. Because, when things are to be done, I see no virtue in doing them, meagerly or poorly, I believe in accepting the financial support for doing them well from an interested public, eager to proffer this support. And because I think that standards of excellence are desirable; attributes of life and that interest and approval of one's fellowmen are not unworthy ambitions in life, and further because I believe that experience in undergoing and accepting criticism of impartial observers is not an unprofitable process in preparation for life,—because of these theories, I am not violently outraged at the interest and comment of columns of the metropolitan press, even if often I would like to change, their emphasis.

Strictly, perhaps, these things have little relation to formal processes of education. Rightly conceived and wisely directed, however, they all have very vital relationship to preparation for life and', thus they cannot be held irrelevant to or undesirable for the college.

Viewing the question in general terms,, the, American college is a product of conditions and circumstances unlike those which have created or perpetuated institutions of higher learning elsewftere. It has arisen and acquired strength because of particular needs and particular opportunities which pertain specifically to economic, social and political conditions in the United States.

The attributes of life within the American college cannot advantageouly be considered in disregard of the attributes of the American people. Whether for good or for ill, the college does not and cannot either quickly or radically change the thinking within its student body which has been instigated and developed by eighteen years of membership in the American home and by more than a decade of susceptibility to the standards of American public interest and opinion. This is a factor entitled to consideration when we undertake to say what should or should not be done in directing the life of a college undergraduate body.

Moreover, as the wave of protest within the colleges against athletics and the attitude of criticism without, bulk higher and larger as a result of recent occurrences, incidental though regrettable, let us reflect upon some of our own obvious characteristics. As a people, we are without concern for nice distinctions in judgment. We think and act on the basis of antipathies. We vote not so much for men whom we admire as against those we dislike. One offence which we deplore or one weakness which we despise figures more largely in determining our judgment than ninety-nine virtues in accord with our general theories of desirable good.

Moderation as a principle, in theory or practice, is held to be a sign of weakness and to be effete. Our confidence and our support are almost invariably given to one or the other of two schools of extremists. One is made up of that supposititiously stalwart and rugged type which holds that what ever is is right, and not only refuses to be stampeded, but refuses likewise to be moved. The other is made up of that much adulated red-blooded, two-fisted type, which is expected to square its shoulders and to charge forward, even if with proverbial blindness it demolishes the pillars, and in striving to correct incidental abuses, brings down the roof in general destruction.

Throughout all of its work and in all of its relations to society, the American college suffers from the prevalence of these characteristics among the American people. The colleges are of necessity acutely susceptible to these attributes, t always. Now, in this matter of intercollegiate athletics, as ever, everywhere, the opposing attitudes of irritated obstinacy against any change and of impulsive desire for violent change, are about equally dangerous to the well-being of the college.

Athletics, as existent in the colleges today admittedly have their grave weaknesses, their serious faults, and their unfortunate influences. Nevertheless, the history of the past quarter century shows not only an eagerness, but a capacity in the field of athletic control for correcting evils and enhancing virtues, viewed in terms of influence upon ideals of community life among undergraduates, that has not been exceeded in other fields of human activity within or without the college.

Under these circumstances, I should personally be not merely unwilling to have athletics subjected to prescriptions of emotional criticism, or astigmatic suggestions for reform, but I should further deplore any proposition that should not include time for deliberation, facilities for fact-finding and open-mindedness in adopting conclusions.

I am not neutral nor passive in regard to this proposition of the essential desirability to college life of intercollegiate athletics. I wish to see them constantly scrutinized and constantly improved. I wish to see a constant study made of the desirable adjustments to the curriculum life of the college, that their virtues may be magnified and their defects be minimized. But I wish this to be undertaken in a spirit of appreciation for the genuine, values which are attached and for the delicacy of some of the adjustments which are involved.

If no alternatives should be offered, however, except the retention of things as they are, or the adoption of a program of only partially thought-out panaceas, I should wish to commit myself to maintenance of the status quo until this could be examined in the light of what might be the effect of suggested reforms and what probably would be the result.

Returning, for a moment, to the distinction which I earlier made, between the curriculum life of the college and the community life, I wish to reiterate this thought. Sense of such indispensable attributes for community life as the will for cooperation, team play, and the willingness to forget self for advantage of the group, are inculcated largely in the community life of the college, and can be but little inculcated elsewhere. Character development, moral stamina, those forms of .generosity which we, call sportsmanship, are produced in the actual life of the college community, and in this the greatest single agency for their production is the institution of intercollegiate athletics.

The stimulated intellect is, of course, the primary purpose of the college. But is not the man whose intellect has been stimulated doubly valuable to society when he is qualified to become an effective agent in the community in which he lives! As a preparation for this, the ideals of the college community have influence beyond reckoning. No agency of undergraduate life so powerfully binds the college community together nor, on the whole, so advantageously permeates its ideals as do the undergraduate sports. Hence, let us not deny them either the consideration or the credit which is rightfully theirs.

Athletics have a desirable place in the American college!

The Telemark turn

An address by President Hopkins before the National Collegiate Athletic Association in New York, December 30, 1925.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA RETURN TO HANOVER

February 1926 By Ben Ames Williams '10 -

Article

ArticleThe editors of this Magazine have been made aware,

February 1926 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1917

February 1926 By Ralph Sanborn -

Article

ArticleHEREIN SOME REMARKS A.RE WELL ANSWERED

February 1926 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1926 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH TWO YEARS PRECEDING THE CIVIL WAR

February 1926 By John Scales '63

Article

-

Article

ArticleARMS AND THE MAN

January 1916 -

Article

ArticleFRATERNITY AVERAGE

February 1917 -

Article

ArticleIntercollegiate Club

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Article

ArticleWith the Outing Club

December 1940 -

Article

ArticleJohn James Audubon, Commercial Traveller

FEBRUARY 1930 By Frank C. Ayres -

Article

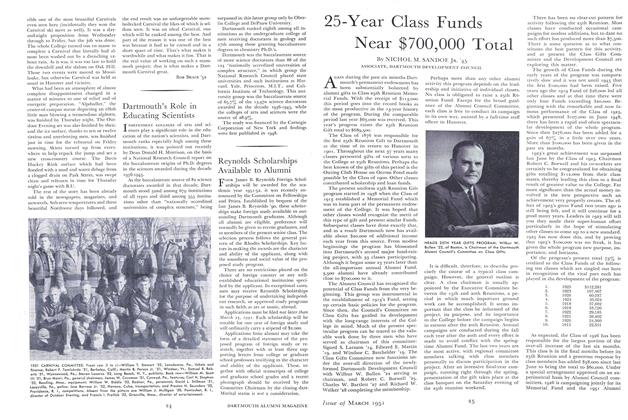

Article25-Year Glass Funds Near $700,000 Total

March 1951 By NICHOL M. SANDOE JR. '45