putting into effect the recent amendments to the Council constitution. The new plan may not even yet be fully understood. Its fundamental purpose is to make of the Council a thoroughly representative body of the alumni. In this capacity it is invested with the, im- portant function of nominating alumni trustees. Formerly the alumni voted for the nomination of alumni trust'ees as well as in the election of councilors though of late years contests we,re very infrequent. Under the plan now in operation contests are assured in the Council districts while there, is no voting on trustees unless this is required by a petition nominating a can- candidate other than the nominee of the Council.

To insure a Council that will express the wishes of the alumni a thoroughly democratic system of nomination and election has been adopted. Each of the five geographical districts is treated as a unit and the electors in that unit are given the opportunity to make a nomination. From the nominations thus made the three alumni in each district most frequently named become thereby the nominees.The voting is then by districts rather than by the alumni at large as previously.

Whatever may be, the virtues or defects of the new method it is at least developing more interest and bringing out a heavier vote than in recent years. The danger that men may be nominated and perhaps elected who are either unable or unwilling to serve is evident, but this weakness is not irremediable. Its greatest asset is the authority it gives the-. Council as a thoroughly representative alumni body.

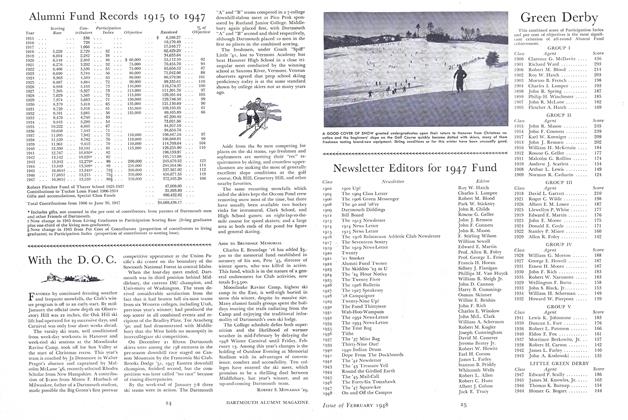

Speaking of the Alumni Fund, as we have already done, an interesting comparison has been brought out by a questionnaire lately conducted by the Wesleyan Alumni Council among the various well established Alumni Funds of the northeastern colleges. It appears from the tabulation that Yale has had an alumni fund since, 1890—by far the longest period of any reported—whereas Brown and Dartmouth, coming next in point of fund longevity, have had such funds for 11 years apiece. Cornell did not specify how long her fund had been going, but from the size of the total raised ($224,009) from some 33,000 alumni last year, one might safely assume that it is not a novel proposition at Ithaca. Most of the colleges reporting state that their fund has been operating for no more than three or five years.

The, striking thing is that Dartmouth, in raising $97,224 from a total of 6687 alumni, actually enrolled 72 per cent of her living graduates as contributors toward the last year's fund—a record not even approached anywhere else. Yale collected from 40 per cent, Williams from 25, Vermont from a trifle over 38 per cent, Rutgers from 40, Cornell from 24, Brown from 25, Beloit (in a single year of experience) from 45 per cent—an extremely creditable showing in the circumstances—and Amherst from 28 per cent. That is to say, of the dozen colleges interrogated, Dartmouth stood easily first in percentage of alumni participating, with almost three-quarters of the entire alumni body represented in last year's fund. It seems to us a record to be proud of as betokening an unusual loyalty. Naturally the universities with enormous bodies of alumni to call upon—as is the case with Yale and Cornell—produce total amounts which smaller bodies

cannot expect to attain; but that is a matter of positive rather than comparative figures. It is in the percentage column, showing what relative part of the alumni assisted, that the story lies in its more interesting form, or in the per capita figures. The latter show Yale with about $12 as the average, Cornell with $7, and Dartmouth with something over $14. Of course there are concealed reasons for some of the differences. In some cases there may have been other coincident drives—for endowment of a permanent sort, for example. In others, no such elaborate campaign to cover the field is made as we make at Hanover every year. Brown, for an instance, raised nearly $53,000 last year without any campaign at all save such as was involved in sending out circulars to 7500 men. Against that element should, howeyer, be set the fact

that Dartmouth has handled incidentally a very considerable campaign to pay for the Memorial Field.

It is felt proper to cite these figures here as a possible incentive to our alumni bod}' this coming season to better, if possible, an already amazing record. It is manifestly impossible to expect to enroll as contributors anything like the full 100 pe,r cent. But it should be possible to exceed 75—which figure we are approaching but have not attained—and very probably we can attain 80 per cent in due season. Our present growth-rate is hfgh and if it continues substantially the same as it is now we ought in the next ten years or so to handle much larger quotas than at present with even greater ease and with somewhat less of intensive effort—although without an intensive effort it would be unlikely that we should much exceed the 50 per cent mark. In any event the recent survey suffices to enhance both pride and confidence.

The list of scholastic casualties in the present sophomore class is said to be due in large part to a change in the system of ratings whereby men are put on probation for less imposing delinquencies than in former years—but it is only in part because of that change that so unfortunate a record has been made, and it may conceivably have some bearing on the zeal with which the Selective Process is applied by scattered alumni, .as well as by the officers directly in control of admissions. In theory—and to a gratifying extent in practice—the selective system promotes a more consistent scholastic excellence on the part of men admitted to college on a basis of what ought to be proved competence for work. But it must be remembered that the scholastic side of the problem is by no means the only element considered. It is intended to admit none but men of intellectual capacity equal to the maintenance of the required standing to remain in college, so far as one may judge by what they have been doing, and in addition an effort is also made to assess the character of applicants on other than scholastic lines, so that a well-rounded body o'f students may be secured when considered from the viewpoint of alertness, interest, appreciation and the like. Properly applied, this should give us, as a general thing, classes capable of losing very few men through failure to maintain the required rank. As a matter of fact it does so—as a general rule. It is obvious, however, that there will be now and again an exception in which a class will score losses heavier than one likes to see; and when that happens it seems fitting to make a thoughtful inspection of the methods of choice, with a view to strengthening points where weakness may develop.

With the purely scholastic aspects of the matter this MAGAZINE has but little concern. That may be left with entire safety to the proper officers of instruction. What is sought to be emphasized here is the suggestion that perhaps the various bodies of local alumni, on whom falls the duty of checking up the general character and aspirations of young men applying from various sections of the country, are not being sufficiently exacting in their rating of the applicants who come before them. If we are to have hand-picked students, admitted because of what our alumni judge to be evidence of special fitness to utilize the opportunities afforded by their college course, it is necessary to make the hand-picking process a matter of real care. It is pleasant to believe that this is already the case with most alumni inspections—but it would be rather easy to become more lax than circumstances warrant and we would therefore stress the importance of being what colloquial speech would call "fussy" about the material which is given alumni approval as manifesting the disposition and character which the College wants.

There will necessarily be mistakes, but with due care and the exercise of inflexible judgment the mistakes ought to be few. For some reason or other the sophomore class has revealed an unusual number of men who couldn't keep up and who have in consequence been forced to sever their connection with the College. It should be a rare and exceptional case, as we believe it is. If it were not, one might have some qualms, either as to the practical efficiency oif the Selective Process,-or as to the stern insistence of those who pass on the hundreds of applicants on the elimination of such as show a questionable qualification.

Ordinary common sense dictates a faith in the process as averaging better than any other for the winnowing of the -applicants. If it falls down now and then, one is justified in questioning, not so much the process itself, but the strictness of its use. What the College is after is the maximum of good material, so that there shall be the smallest possible number of misfits on whom it is folly to waste the College's time and effort. The large number of separations recorded this year in a single class should not be over-emphasized—nor, on the other hand, should it be ignored.

Not the least important of the details of mechanism for keeping the alumni interest of the College at its highest efficiency is the annual gathering of the Secretaries Association at Hanover in the early spring. In fact it may well be the most important of the several agencies for inspiring and maintaining that interest. President Hopkins has often remarked on the wholly extraordinary part which the graduates of the College play in the assistance of the administration, and probably there is no one of us who has not felt the same. A whole-hearted and active cooperation between the College in Being and its widely scattered sons, implying that the alumni are an integral part of the organization and recognize the fact, is thoroughly to be desired. By the dissemination of knowledge concerning affairs at Hanover through the various class secretaries we believe more is done to inspire and retain that cooperation than is accomplished by any other single device in the whole alumni organization.

Those secretaries who come to Hanover in the spring—and the custom is happily for every such official to come if he can, or to send a substitute if he cannot come himself—can scarcely avoid inspiration. One feels that the College really wants one to come, and honestly welcomes participation in the solution of its problems. There are occasional outbursts credited to college executives elsewhere to the general effect that "if the alumni would only let the colleges alone" they would get along better—but one never hears any such sentiment as that at Hanover. We doubt that any other college in the country goes so far in making the alumni body feel its vital concern for the institution, or does so much to lay before the thousands of graduates intimate information as to what is going on, or as to what is contemplated. The idea is thoroughly democratic, and we believe thoroughly sound.

Every class secretary is the administrator of an exceedingly important trust. He is the connecting link between the men of his own class and the College. If he is the right man for the place—and most class secretaries are—he functions with both efficiency and enthusiasm. He knows more than any other man about his classmates and he is in position to relay to them detailed information, which it is probable they will be glad to have and on which they may base the practical side of their college relationship. It is peculiarly gratifying to know that so many make it a point to return every year in late April or early May to Hanover to participate in a meeting which is of such vital moment as that of the Secretaries' Association.

The final word must infallibly rest with the administration itself in matters of college policy—i.e., with the President and Trustees. It is, however, essential to canvass alumni opinion, especially where the alumni play so important a part in the annual problem of financing the College, in order that the governing body may know and assess at its appropriate value what the alumni think; and it is likewise important that what the alumni think shall be based on accurate and complete knowledge of what the College is about. To that end the class secretaries are annually convened at Hanover, and with the lapse of years this meeting has come to be regarded by both sides—the administrators and the alumni alike—as one of the most significant and most useful events in the college year. One thing that has probably impressed most of the committees engaged in sifting applications for admission to Dartmouth College, in the process of interviewing the young men of various localities, is the very general expression of a preference for a college in the country, as against one in the city. It is reported by many engaged in this task that such a preference is very commonly asserted by boys when asked just why they chose Dartmouth rather than some other place —in the absence of some more direct incentive, such as the possession of some relation who had been to Dartmouth, or the inducement offered by the choice of some close school-friend to go there. The fact of being in the country appears to count as a very potent influence in Dartmouth's favor, especially among boys reared in cities. One recalls the day when this kind of location often seemed a handicap, but it is obviously not so now with a great multitude of lads. The yearning to be away from the confusion, dirt and bustle of a city is naturally strongest in those who have had a surfeit thereof, and it is in itself a distinct credit to those who profess the feeling because it shows a natural leaning toward the more wholesome atmosphere of the unpolluted countryside. Whether it is the freedom from urban temptations that appeals most, or the greater freedom of out-door-life, or the natural beauty of the surroundings, who shall say? The fact is that more boys in 1926 are alleging a rural location as a good reason to prefer Dartmouth than would have been likely to do so in 1890.

Those who have handled application blanks this year for rating applicants on points other than scholarship have doubtless found in some respects helpful, and in other respects hampering, the new form of blank used for tabulating the next class. These blanks have sought to lighten the labor of investigators and at the same time guide them, by suggesting a variety of special points which it is desirable to mark—points relating to personal appearance, intellectual alertness, reasons for selecting Dartmouth, liability to do well or ill in the matter of utilizing opportunities, and so forth. Not every item in the list has commended itself to such as have commented on this matter in our hearing, nor has every item been clearly understood. There have been instances of perplexity due to the inability to rate a man either way when definite alternatives were suggested—the usual disposition apparently being to give a boy the benefit of every doubt. In past years the blanks offered no such suggestions, but provided a blank page on which the investigator was supposed to write a brief but candid essay after talking with the "prospect." It remains to be seen whether or not the new method commends itself widely to those who do the work. On the whole, one suspects that it will. But there remain some who express a bit of wonderment as to what they ought to do with an entry like "Poise," and a few who would rather write out generalities than check alternative entries such as "Intellectual Purpose strong" (or mild, or weak, as the

case may be). This work is not always easy to do. It is asked of busy men the country over, and at the outset they are usually more embarrassed than are the boys who file before them for inspection. After a little, in our experience, it becomes simpler and the inquiry is likely to proceed with a better understanding on the part of the interviewer of what he ought to discover. Perhaps the most vital thing of all is the establishment of the boy's real reason for going to any college—and this is by no means the easiest to uncover. It is so easy to say vaguely that one wants "to pursue education," when in reality the idea is to do what it is the fashion at present to do, or to seek alluring associations, or to have a good time—this last being generalized on the blank as "the Country Club idea." It would be interesting if the Director of Admissions would report how many blanks he receives checked on that unflattering item. For a guess, there will not be many.

Nevertheless we must believe that this work, if faithfully and discerningly done, has a very great value to the College. We would therefore renew a plea made several times before that alumni all over the country hold themselves in readiness annually to answer the call, if it comes to them, to assist in this brief but very useful way by reporting on the applicants from their neighborhood. The College knows already about the scholarship of these applicants. All it wants of the alumni is a report on a boy's general characteristics, his repute at home, his looks, his quickness or his sluggishness, his general theory underlying his hope to go to college, and his concrete notions whe,n it comes to selecting Dartmouth as the college of his choice. Generally speaking, no doubt, the impression the examiner gets from his total conversation is more accurate than that he derives from responses to any particular question.

The College has expressed a preference for composite judgments on these applicants, rather than the individual impressions of any single alumnus in the vicinity. That has proved not always to be possible, but where it has been done the experience has been illuminating. A composite, judgment sometimes represents a unanimous feeling on the part of four or five men, but more usually a conclusion reached after debate. In any event, the hope is thus to winnow out a good deal of chaff and insure a larger percentage of real grain for the college mill, by warding off boys who seem to be unpromising material on which to operate. Mistakes will doubtless occur, and injustice may be done here and there in the, case of a light hidden beneath a bushel, or in the case of a rough diamond. In the main it is probaable, that the judgments will be found both accurate and helpful to the better working of the Selective Process.

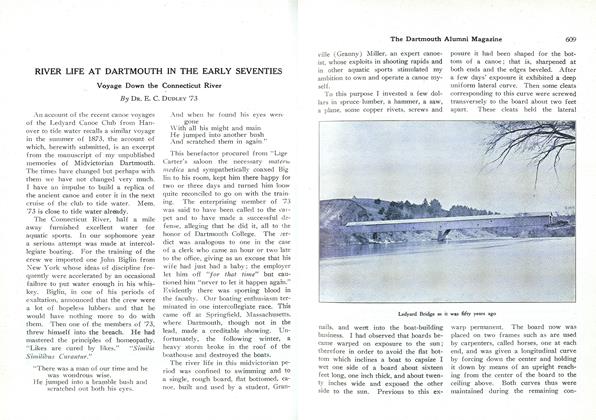

Looking down on Ledyard Bridge

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWATER FOR HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE

May 1926 By Robert Fletcher -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1926 By L. J. Heydt -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1926 By L. J. Heydt -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

May 1926 By H. Clifford Bean -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH GREEN

May 1926 By The Rev. Roy B. Chamberlin -

Article

ArticleRIVER LIFE AT DARTMOUTH IN THE EARLY SEVENTIES

May 1926 By Dr. E. C. Dudley '73