Commenting on an editorial in this MagazinE the Des Moines Register inclines to dissent from the proposal that students in colleges be asked to pay about what their education costs, holding that to do so would be a denial of equal opportunity and would, if carried to a logical conclusion, be equally an argument for doing away with the public schools, confining them to pupils who could afford to pay. "The point is," says the Register, "that education is one of the basic things for social advancement; and not merely for the sake of individuals, but for the sake of the body politic, it should be as freely available as it is possible to make it."

The MAGAZINE is unable to follow this argument. If there is this analogy between college education and common school education on the score of social advancement, then logic would seem to demand doing away with college tuition fees altogether. At present the pupil of the public schools pays nothing at all. The schools are free to him. The student in a college (excluding state universities maintained as part of the public school system) pays a tuition fee which varies in size with the colleges, but is on the average about half what the education costs. If "equality of opportunity" is denied by a fee which would cover the whole cost, it is also denied by one covering only half the cost. It looks as if the present college education—sold at halfprice to rich and poor alike—were neither the one thing or the other; neither a forthright charity, nor a businesslike proposition.

It would be rather hopeless to enter on a discussion of the net -benefits to the body politic in case it were made freely possible for every youthful citizjen to start with the kindergarten and emerge an A. 8., all at public expense. One may doubt that it would be so advantageous as the critics seem to believe. There is room for the feeling that more young people are going to college already than is profitable, either to themselves or to the country, although to utteT that thought usually prompts a charge of heresy. It is not an easy thing to draw the line between that education which is so vital to the well-being of a republic as to justify compelling every citizen to acquire it, and to warrant the public in providing the mechanism to enable it, and the education which represents something rather beyond the "quintessential sine qua non." As the scope of public education steadily broadens to include things which formerly were not regarded as appropriate topics for free public instructiondomestic and practical arts, for example —and as the tendency is for grammar schools to become miniature high schools, while high schools become miniature colleges, it is the more difficult to draw this line between what one may call the "unalienable right" of every citizen and the luxuries of an educational sort, which have until lately been regarded as things for such as seriously wanted them, or could afford them. It may be that there is no such line—but as to that we have serious doubts. In the last analysis, the argument of the Des Moines Register seems to us to mean that it is the duty of the state to throw open to every growing citizen free educational facilities of every sort, denying to no one the free opportunity to make himself a lawyer, a doctor, a dentist, or professor, as well as a carpenter, electrical engineer, teacher, or plumber.

It ought not to be forgotten, by the way, that in this urgence to make tuition charges more nearly equal the actual costs of education there is no intent to deny the provision of student-aid funds. It is merely insisted that instead of yielding half what the tuition costs such scholarship endowments ought to be calculated to yield pretty nearly the whole cost. Instead of deriving $3OO a year from his scholarship, the aided student should derive $6OO, let us say. That would mean fewer scholarship funds, but larger ones. Xo one is so hard-boiled as to demand that none but rich students ever get a chance, for that would clearly be a wretched arrangement for all concerned —for the colleges most of all.

Meanwhile the question appears to be whether colleges ought to charge anything whatever—taking the argument of the Des Moines Register. Is the college properly to be regarded as a loftier type of public school? Would it advantage the United States as a body politic, or benefit its individual citizens, if it were? One difficulty in considering such questions is sure to be the ease with which demagogical bathos can be talked about it, submerging common sense in an emotional deluge. Outcroppings of that have been noted much nearer home than Des Moines.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

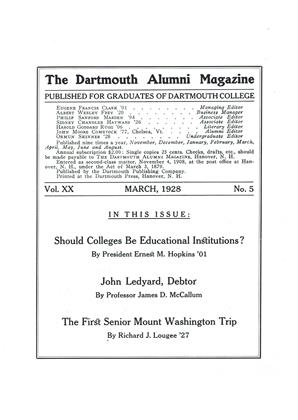

ArticleSHOULD COLLEGES BE EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS?

March 1928 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

March 1928 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

March 1928 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1927

March 1928 By Doane Arnold -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

March 1928 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

March 1928 By Frederick W. Cassebeer