Assaults on collegiate education from so-called "practical" business men have been rather frequent of late, including not merely the detailed arraignment at the hands of Mr. Roger Babson, often referred to in these and other columns, but also a no less elaborate indictment emanating from the energetic Clarence W. Barron, financial seer and proprietor of the Boston News Bureau. To these assaults it is natural there should be reply, and not the least notable by any means was that offered by President Hopkins early in January at a luncheon of the University Club in Boston, in which, while not admitting that the record revealed any conspicuous failure on the part of the colleges to serve the field considered primarily by the Barron-Babson survey, the Dartmouth president expressed his belief that such a field must in any case be too narrow to warrant the exclusive attention of college administrators. In other words, even if it were to be admitted (which it is not) that the colleges are not recruiting the ranks of American, or New England, industry with able graduates, there is room for the contention that it is not primarily the aim and object of education to perform that special function.

Dr. Hopkins filed a special dissent from the proposition that the value of the American college is to be judged by its effect of enhancing prosperity, or that its major function should be to enable business to be successful. The function of the educational institutions is to educate— to stimulate more and better thinking, to turn out men with minds capable of working accurately and usefully, and to contribute somewhat to the ennoblement of me,n's souls as well as to enhance the efficiency with which they surround themselves with corporeal luxuries.

We believe it to be an untenable theory that the major business of the United States derives no benefit from college and university training. The president cited a few instances, currente calamo, which occurred to him as proving that men of high educational attainment were taking their part in the responsible direction of the country's most imposing business concerns—it happened that a Dartmouth graduate, now head of the United Fruit Company, was actually presiding over the meeting at which Dr. Hopkins spoke—and a sufficient number of citations was assembled to offset Mr. Barron's specification of Vanderbilt, Rockefeller and Henry Ford. One who glibly condemns the colleges for failure to recruit the ranks of Big Business does well to make sure, first, of his premises. It might be added that Big Business itself appears not to hold the American colleges in quite the degree of contempt manifested by Mr. Barron, or Mr. Babson that such gifts as have been bestowed on educational foundations by leaders like Mr. George F. Baker, the Rockefellers, Mr. Carnegie, and Mr. Eastman betoken what looks like an important dissent from most of the Barron-Babson dicta; and finally, as Dr. Hopkins acutely pointed out, that without painstaking research in scores of obscure laboratories, the, Henry Fords, Rockefellers and Vanderbilts would have labored in vain.

One had rather hoped that the day requiring such arguments was over. That there is no very general concurrence in the Barron assertion that the modern college, is "a curse" may be spelled quite easily out of the unprecedented increase in public demand for college education. The old-time contempt for what used to be called "book larnin'" is seldom heard, and it comes with a curious sound from the lips, or pens, of financial specialists. But chiefly we regret it because it tends to emphasize so inordinately the idea that the function of college education is materialistic, and ignores the functions which imagination and vision have always played, indeed always must play, in the progress of even the material sciences, or in business. It is difficult to avoid the feeling that education con ducted according to the ideas of either Mr. Babson of Wellesley Hills, or Mr. Barron of the Boston News Bureau, would be a far poorer thing than it is now—though no one, least of all sensible educators like President Hopkins, would dream of claiming that it is without its present defects. Ne sutor ultra crepidam. The business man who dabbles in education is seldom convincing when he finds fault because he is little convinced by the educator who dabbles in business. Meantime it is worth remembering that, taken as a whole, the business world by no means reveals a general concurrence in the low estimate of the educational world which is voiced by these clamant critics. As for the true function of the college it was well summed up in the closing paragraph of the Boston address of President Hopkins when he said,

"It is the responsibility of education to scan the far horizon; it is the obligation of education, if need be, to undergo attack, to accept contempt and to endure derision from contemporaries who are more interested in maintaining their own opinions than they are in knowing what is really so. It is the function of education, when error is found, to denounce it; it is the privilege of education, when truth is found, to proclaim it."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

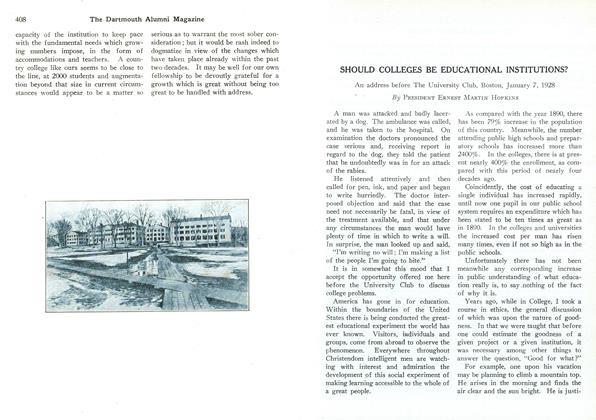

ArticleSHOULD COLLEGES BE EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS?

March 1928 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

March 1928 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

March 1928 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1927

March 1928 By Doane Arnold -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

March 1928 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

March 1928 By Frederick W. Cassebeer

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

December 1948 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Takes Coeducation Stand

MAY 1971 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Trustee Nominated

February 1974 -

Article

ArticleTennis in Tigertown

APRIL 1992 -

Article

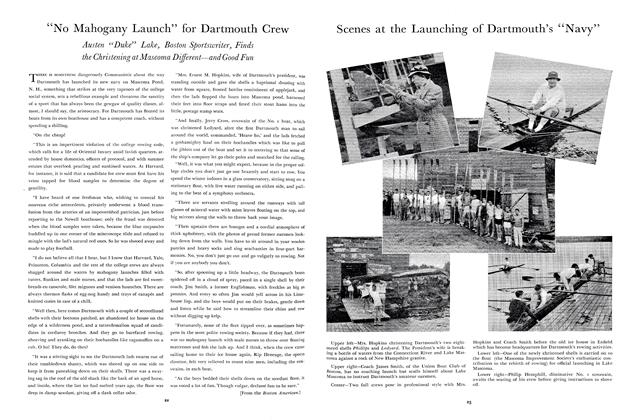

Article"No Mahogany Launch" for Dartmouth Grew

June 1934 By [From the Boston American.] -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH EDUCATIONAL ASSOCIATION

January, 1925 By Rbert J. Holmes '09, Treasurer