The great difficulty in commenting on President Hopkins' admirable article in the January Scribner's bearing the above title arises from the constant temptation to quote from it verbatim because of the inability of which one is conscious to restate the same ideas in equally compelling words. The article is a thoughtful consideration of the frequently made claim that the modern American college is not carrying out the faith of the fathers, in the course of which the Dartmouth president cautions the readers not to confuse the faith of the fathers with their works, and not to confound their spirit with the steps which, in their day and generation, they took to give that spirit expression. It is a picturesque and arresting assertion that it was the faith of the fathers which pressed to the lips of Socrates the cup of hemlock, which crucified Jesus, which restrained Roger Bacon from giving to the world discoveries in science for which he knew his contemporaries were not ripe, and which compelled Galileo to declare to be false what he knew to be true. In fine, the faith of the fathers can be overdone, provided one misconceives what it really was. It is salutary to consider what men of that faith, who acted as they did under conditions no longer obtaining, would do today under the conditions which currently prevail.

The president is not in any sense belittling the faith of the fathers, when properly apportioned as faith. He merely insists that we take changing environments into consideration as factors affecting the avenues through which such faith still seeks to attain its objectives. His assumption is that the same sort of inspiration is operating today; but one must not suppose that the fathers themselves, if they revisited these glimpses of the moon, would do things now exactly as they did them then. Washington, Jefferson, Hamilton and the rest would very probably entertain distinctly different notions of the details of politics from what they entertained in 1787, while retaining the same general spirit; and Dr. Hopkins intimates that in the realm of religion much the same alterations would probably obtain in the case of Isaiah, or even Jesus. "Tempora mutantur, at nosniutamur in illis" remains at least a partial truth—but, if we catch the president's idea, it is rather that we change more with respect to the methods calculated to attain our ideals than with respect to the ideals themselves. The letter killeth; the spirit maketh alive. It is important to recognize that much of this talk about the abandoned faith of the fathers in collegiate matters relates not at all to the spirit, but only to the letter whereby that spirit was once spelled out.

The great aim of college education, we are told, is to enlarge the individual's capacity for thought rather than to fill the pigeonholes of the mind with predigested information. Naturally there must be more or less of the latter as the indispensable material for getting started: but after all the object is1 to make the mind a working, productive mechanism, and not a mere storehouse. The eternal quest is for truth, and the quarry is elusive. It was thus with the fathers, who followed what seemed in their time to be the methods best adapted to the search. It is so with the sons, who find it necessary here and there to change those methods. The quest remains the same. Better even a wrong method, says the writer in effect, so long as it is founded on right aspirations, than a right method wholly uninspired.

It should not be thought that this presupposes a disregard for the accumulated experience and wisdom of the past. It merely asks that the past and its needs be not unduly exalted, or assumed to be identical with the necessities of the future to such an extent that all truth will be regarded as having crystallized permanently during ages past. There should even be some boldness of anticipation, in things spiritual as well as in things industrial. The scrap-heap, that limbo of discarded things, is an inseparable adjunct to all progress. By no means everything in such an accumulation of the outworn is a reminder of past mistakes—very little is such, in fact. But the thing which was highly useful then may be worse than useless now—as the material world knows well. It is the same with the spiritual, in which

"Our little systems have their day, They have their day and cease to be; They are but broken lights of Thee— And Thou, O Lord, art more than they."

This Scribner's article from the president's pen seems to us one of the most illuminatingly constructive outgivings in matters educational published in a long time. It is a strong plea to avoid confounding means with ends; and with it is coupled a very needful reminder that the youthful mind of today, with all its epochal defects (such as a lack of appreciation of the duties of self-discipline) is not to be underrated, or regarded as in any wise inferior to the youthful mind of an older generation, when it comes to its capacity for independent thought, or for cherishing ideals- of human conduct. The faith of the fathers still lives and still inspires. If it differs in concrete manifestations, that is the necessary consequence of a changing material and intellectual world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

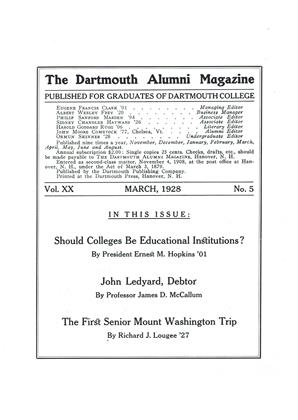

ArticleSHOULD COLLEGES BE EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS?

March 1928 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

March 1928 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

March 1928 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1927

March 1928 By Doane Arnold -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

March 1928 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

March 1928 By Frederick W. Cassebeer