Psychology as a new biological science is an idea that may be hard to grasp. The fact is, however, that modern psychology is committed to the laboratory and the use of scientific experimental techniques. It has devised an experimental technique for tests of that elusive variable known as "Intelligence." A study of the transition from the crude beginnings presents an astounding advance from the raw army tests to our modern tests for scholastic aptitudes. In the field of learning, controlled methods are employed to make data meaningful, and not inferential. The emotions, crude and cultured, are studied directly and indirectly. Even the abstract, acquired abilities, as appreciation of art, e.g., have been put to test. Then, of course, there remains a vast experimental literature on the functioning of the sense organs through which the various data of everyday "experience" are supplied.

In such measure as this program is adhered to, psychology is a science. It is at work cleaning its house of the discarded theories of phrenology, imagery-types, and of the grossly mistaken concepts of the "unconscious mind," the "group mind," and of the various "faculties." It has constructive fact to replace these thin devices of speculation.

In all this, there resides a biological science. Some find too much theory, failing to grasp the theoretical basis of all knowledge. They doubt that all knowledge is finite, being limited to man's sensitivity to it, and awaiting man's cleverness in devising instruments suited to that type of study. The science of psychology is engaged at present in trying to invent those instruments and techniques, and to throw out of court those false methods, as phrenology, palm-reading, astrology, and other pseudo-sciences.

Fortunately, the majority of our students are willing to look beyond the meager horizon of the pseudosciences. They are more and more showing a willingness to study psychology for what it really is: the science of human behavior.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

December 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

ArticleAlumni Associations

December 1929 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meets in New York

December 1929 -

Article

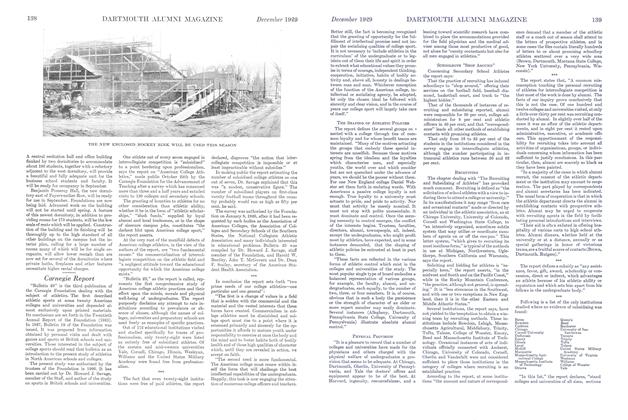

ArticleCarnegie Report

December 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Indians

December 1929 By Eric P. Kelly -

Sports

SportsThe Yale Epic

December 1929 By Phil Sherman

Instructor Chauncey N. Allen

Article

-

Article

ArticleBriefly Noted

DECEMBER 1963 -

Article

ArticleGIFTS, GRANTS & BEQUESTS

JULY 1969 -

Article

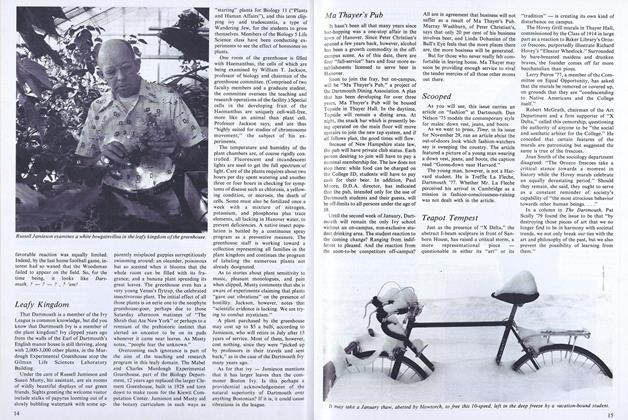

ArticleMa Thayer's Pub

December 1976 -

Article

ArticleDid the recent cloning of a sleep catch the ethics community off guard?

MAY 1997 -

Article

ArticleHOLY WEEK

MAY 1930 By Craig Thorn, Jr. -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

OCTOBER 1931 By W. H. Ferry '32