For opinions which appear in these columns The Editors alone are responsible

A BREATHING SPACE

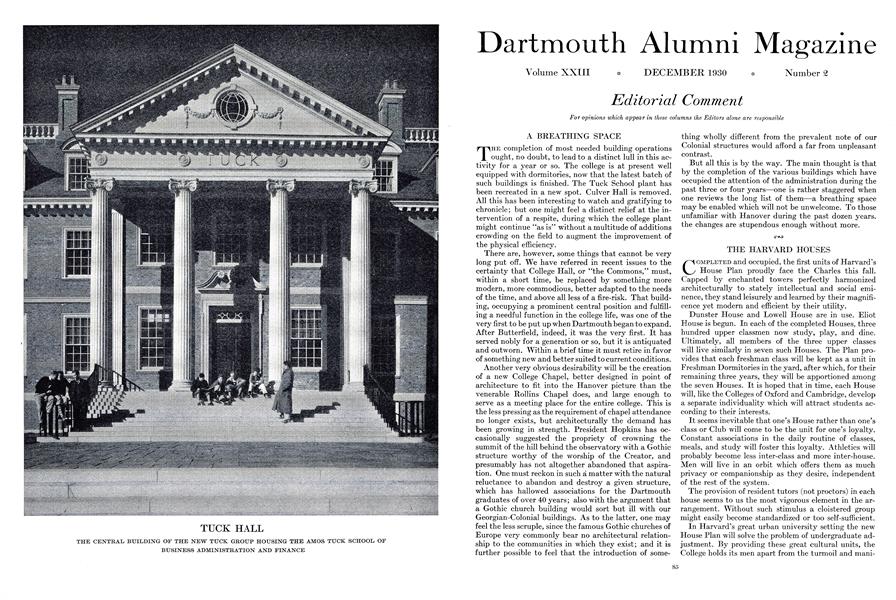

THE completion of most needed building operations ought, no doubt, to lead to a distinct lull in this activity for a year or so. The college is at present well equipped with dormitories, now that the latest batch of such buildings is finished. The Tuck School plant has been recreated in a new spot. Culver Hall is removed. All this has been interesting to watch and gratifying to chronicle; but one might feel a distinct relief at the intervention of a respite, during which the college plant might continue "as is" without a multitude of additions crowding on the field to augment the improvement of the physical efficiency.

There are, however, some things that cannot be very long put off. We have referred in recent issues to the certainty that College Hall, or "the Commons," must, within a short time, be replaced by something more modern, more commodious, better adapted to the needs of the time, and above all less of a fire-risk. That building, occupying a prominent central position and fulfilling a needful function in the college life, was one of the very first to be put up when Dartmouth began to expand. After Butterfield, indeed, it was the very first. It has served nobly for a generation or so, but it is antiquated and outworn. Within a brief time it must retire in favor of something new and better suited to current conditions.

Another very obvious desirability will be the creation of a new College Chapel, better designed in point of architecture to fit into the Hanover picture than the venerable Rollins Chapel does, and large enough to serve as a meeting place for the entire college. This is the less pressing as the requirement of chapel attendance no longer exists, but architecturally the demand has been growing in strength. President Hopkins has occasionally suggested the propriety of crowning the summit of the hill behind the observatory with a Gothic structure worthy of the worship of the Creator, and presumably has not altogether abandoned that aspiration. One must reckon in such a matter with the natural reluctance to abandon and destroy a given structure, which has hallowed associations for the Dartmouth graduates of over 40 years; also with the argument that a Gothic church building would sort but ill with our Georgian-Colonial buildings. As to the latter, one may feel the less scruple, since the famous Gothic churches of Europe very commonly bear no architectural relationship to the communities in which they exist; and it is further possible to feel that the introduction of some

thing wholly different from the prevalent note of our Colonial structures would afford a far from unpleasant contrast.

But all this is by the way. The main thought is that by the completion of the various buildings which have occupied the attention of the administration during the past three or four years—one is rather staggered when one reviews the long list of them—a breathing space may be enabled which will not be unwelcome. To those unfamiliar with Hanover during the past dozen years, the changes are stupendous enough without more.

THE HARVARD HOUSES

COMPLETED and occupied, the first units of Harvard's House Plan proudly face the Charles this fall. Capped by enchanted towers perfectly harmonized architecturally to stately intellectual and social eminence, they stand leisurely and learned by their magnificence yet modern and efficient by their utility.

Dunster House and Lowell House are in use. Eliot House is begun. In each of the completed Houses, three hundred upper classmen now study, play, and dine. Ultimately, all members of the three upper classes will live similarly in seven such Houses. The Plan provides that each freshman class will be kept as a unit in Freshman Dormitories in the yard, after which, for their remaining three years, they will be apportioned among the seven Houses. It is hoped that in time, each House will, like the Colleges of Oxford and Cambridge, develop a separate individuality which will attract students according to their interests.

It seems inevitable that one's House rather than one's class or Club will come to be the unit for one's loyalty. Constant associations in the daily routine of classes, meals, and study will foster this loyalty. Athletics will probably become less inter-class and more inter-house. Men will live in an orbit which offers them as much privacy or companionship as they desire, independent of the rest of the system.

The provision of resident tutors (not proctors) in each house seems to us the most vigorous element in the arrangement. Without such stimulus a cloistered group might easily become standardized or too self-sufficient.

In Harvard's great urban university setting the new House Plan will solve the problem of undergraduate adjustment. By providing these great cultural units, the College holds its men apart from the turmoil and mani fold activities of the graduate schools; gives them a palatial province which should encourage spacious, unhurried thinking; and engenders a loyalty based on group associations and companionable understanding (there is a fireplace in every room).

At Dartmouth, instead of isolating the student body from the specialized schools, we have planned to insulate the graduate schools from the more leisurely pace of the liberal college. Dunster House, Lowell House and Tuck School all represent the best in modern scholastic colonies. Similarly they illustrate graphically the problems of the city university as against those of the country college.

Harvard's large scale experiment in educational method will be watched with interest and appreciation by Dartmouth men who extend good wishes for the success it merits.

STARTING THE SEASON

THE football season this year, as always, was three or four weeks in getting into its stride. This is true of pretty nearly all the colleges in the northeast, whatever be the fact with those in the heart of the country. The custom of playing the first three or four games against teams from smaller colleges has become fairly well established and it is only after these rather meaningless contests have been got out of the way that the real interest begins. Not unnaturally there has sprung up criticism of the practice, which seems to be growing. There is heard a demand that the more considerable colleges avoid the playing of games of this natureusually denominated "set-ups"—and adopt a different kind of schedule which shall involve games affording a more significant test of material rather than a walkover, the result of which is a foregone conclusion, the points piled up varying from the upper thirties to two or three score.

It is easier to share in the feeling that this situation is unfortunate and uninteresting than it is to suggest practicable remedies for it. The devising of a schedule such as the critics demand would be difficult and perhaps impossible. Most of the larger football-playing colleges would approach the task with reluctance, and not a few of the smaller ones would regret to lose the chance which such games afford them to gain not only valuable experience, but also a momentary prominence, to say nothing of the "gate" which has come to be a very considerable incentive since the receipts from the football season notoriously finance all the rest of the athletics in every college. It is, however, not to be denied that there is little material for feverish interest in the first three or four games which the average eastern college customarily plays; and while the practice thus provided is at once rather encouraging to untried men and by no means without its value when a big team is shaping into form, it is doubtful that it gives much of a line on what sort of team the college is developing. It is not until later on, when Harvard meets the Army, or Dartmouth meets Harvard, or Yale locks horns with Dartmouth, that one begins to find out what sort of stuff those teams are really made of—i.e., when they tackle foemen worthy of their steel.

No doubt with all the pressure that is being exerted in favor of a change there will be serious thought given to the idea that a better schedule can and should be devised, in which there would be few or no "set-ups"and possibly a system can be invented which would give a better idea at the close of the playing season which team was really the best in each given group. As it is now, there is often a disconcerting array of victories by each of the larger colleges against various others, leading to the quaint result that, as one has beaten another, which in turn has vanquished a third, which latter on still another day has triumphed over the first, practically all have a certain claim to championship rank. It is a complicated matter, however, to devise a scheme which will be satisfactory all around in a season which is necessarily rather short and which involves a game liable to produce a long list of injuries, not serious but damaging to the playing list, if the games are to be without exception what are usually called "hard" games.

It is the sort of thing that will best be left to the experts in such matters. Side-lines criticism is easy enough always, but those of us who are not intimately concerned with the intricacies of the football world certainly have no sufficient conception of all the bearings and angles that are involved, to constitute us competent advisers.

POSTHUMOUS MILLIONS

THE late Asa Wilson Waters, Class of 1871, desiring to make a substantial gift to his alma mater but not having it in his power to give that bequest the form of immediate and actual cash, left a most unusual provision in his will designed to accomplish the desired result in the progress of time. Summarized, his idea was: something like that of Benjamin Franklin in making his famous bequest to the benefit of the citizens of Boston. It consisted in the immediate gift of a principal sum of $1500, which should be treated as the nucleus of a future fund growing out of its careful investment and reinvestment during the next 150 years, with the reasonable expectation that within that time by the natural process of increment it would ultimately reach a total of between a million and a half and two million dollars, which thereupon would constitute the "Asa Wilson Waters (Class of 1871) Sesquicentennial Endowment Fund." The form of investment is rigidly restricted by the testator to such securities as are legally approved for fiduciary institutions in conservative commonwealths, the income to be used meantime for no purpose whatever but the steady increment of the fund.

How far it would be possible or advisable for this method of bequest to be availed of by other testators may be open to debate; but the idea seems wholly feasible as applied to occasional instances and certainly suggests a means whereby those anxious to leave an enduring memorial may accomplish it by postponing the period of fruition in the case of a gift that is originally not of great amount. Its one disadvantage lies in the protracted period of postponement during which the usufruct of the gift is available only for the increase of the gift itself, with the possible outcome that by the time it is ripe to be gathered the object for which it was given may have withered away. That, however, in view of Dartmouth's more than 150 years of past history and present vitality, seems a contingency so remote as to be virtually negligible. The period covered by Mr. Waters' bequest is not greatly different from that stipulated by Franklin in providing for the fund which Boston today finds so useful.

POST DARTMOUTH

AT the desire of the administration the Alumni Council has recently compiled and published in a pamphlet of convenient size, under the above title, certain salient facts, which it is felt to be important the newly fledged alumnus should know, concerning the position which the alumni of Dartmouth occupy with relation to the College. This pamphlet was designed to be circulated among the members of successive graduating classes and has been sent to the personnel of the class of 1930, as well as to class secretaries and others presumably interested. The idea is to continue supplying this information to the graduating classes as they come along, at least so long as the facts embodied in the report undergo no important change.

The relationship subsisting between the College administration and the several thousand alumni scattered over the country has been a marvel to numerous commentators, who have been surprised to observe that at Dartmouth the alumnus is not regarded as a barely tolerable nuisance, endured only because his enthusiasms could be capitalized in drives for money. It is with the idea of perpetuating the present wholesome conditions and explaining the bases on which they rest that this thin volume is presented. It deals with various phases of the problem—the method of securing alumni representation on the Board of Trustees, the Alumni Council, the Class Secretaries and Class Organization, the Alumni Fund, the Athletic Council and so forth—which an undergraduate has no interest in while he remains in statu papillaris, but which suddenly become of importance when he assumes the honorable estate of an alumnus. It is well to make it widely understood why the Dartmouth alumni are not looked upon as a pestiferous body by those who have the management of the College in hand and to detail .the methods by which their influence is exerted.

No one cognizant of the situation ever thinks of the alumni as a body having only a remote or casual interest in Dartmouth, which finds its expression only through the contribution box, or at mid-winter dinners, or quinquennial reunions, or in the Stadium or the Bowl. For this there is a reason, which the "Post Dartmouth" pamphlet endeavors to make plain. The effort was to produce something which should set forth the facts in brief and hopefully readable form, not discouraging to the new alumnus.

THE SENIOR FELLOWSHIP

THE founding of Senior Fellowships at Dartmouth marks again the College's happy opposition to those educational notions, sprung from a vague humanitarian philosophy, which have become notorious for their unwillingness to make the distinctions prerequisite for the flourishing of a vigorous national intelligence; I refer to illegitimate deductions from the democratic principle analyzed so sharply by Renan and Matthew Arnold. It is an opposition shown previously by the establishment, some years ago, of Honor courses. One may consider the two to look forward to the forming of that "aristocracy of brains" of which President Hopkins speaks, to the recruiting of a class able to offer to America the discipline and traditions of which it stands in need. And it is a hope that seems well-founded, for it rests on a society to be built by work and emulation.

The merit of the fellowships then is to have affirmed the dignity of the student and his place, as a man of culture, in the modern world. The difficulties, I think, reside in the choice of the fellows; the dangers, in their choice of studies. Ideally, the award should cause no derangement in the choice of studies; in history, philosophy, and letters, the fellows should follow the law of their own progress. So with me; I thought this honor, which gave license to abandon a plan made previously in accordance with the suggestions of my instructors, would serve best to confirm it. I passed the year in reading Greek and Latin literature, in writing a little. My only venture, a memorable one, was an essay into philosophy, from the poets to Plato and Aristotle. It was a year spent, too, in such association with a group of gentlemen and scholars as shall always be my richest remembrance of Dartmouth. I know that the ancients can live again, and that in their wisdom the problems that beset us are illumined. But these are joys in the day of decline for these studies unfortunately known to few.

In England the title of Senior Fellow is reserved for the most reverend of the dons of a college, a man old and very wise. It is a comparison most apt to prompt the benevolence of my readers for those who are very young.

Senior Fellow, 192,9-30

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe New Tuck School Plant

December 1930 By Dean William R. Gray -

Article

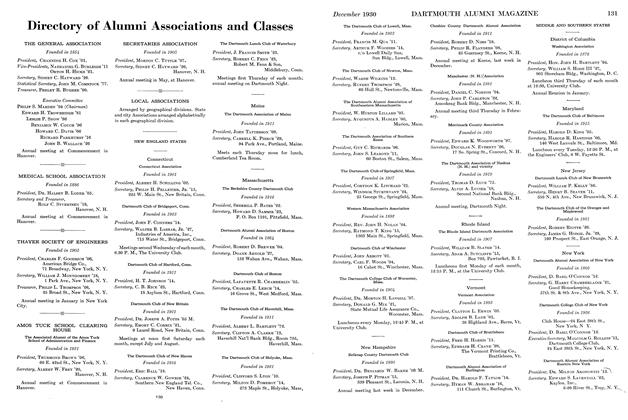

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

December 1930 -

Article

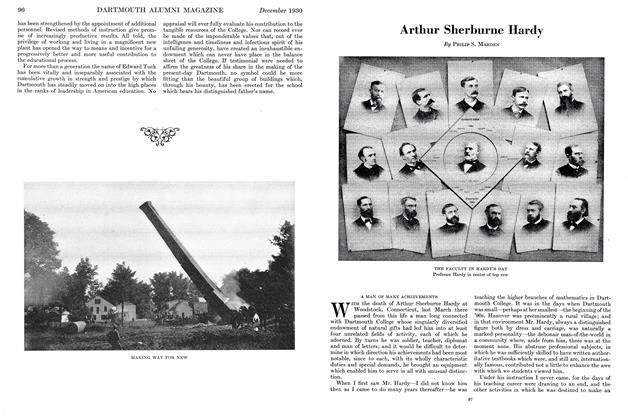

ArticleArthur Sherburne Hardy

December 1930 By Philip S. Marden -

Article

ArticleHarry Hillman: A Dartmouth Institution

December 1930 By Phil Sherman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

December 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

December 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

APRIL, 1927 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters

June 1933 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters From Bolte

November 1941 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorSettling in in Hanover

JUNE 1983 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorVisions and Revisions

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Real World

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Douglas Greenwood