By Harold Ordway Rugg '08. New York. Harcourt, Brace and Company,

"To educate means to provide an environment and experience that will develop in every boy and girl in America the traits of the cultured man." These are words of noble optimism that doubtless exist in the Platonic pattern world of every teacher, from the white New England schoolhouse to the concrete and steel structures of the metropolis. One would gladly share such optimism but experience prevents. The democratic implications of equality may be applicable in the realm of politics but certainly not in the more delicate world of ideas and of artistic sensitiveness. Not every man can be a "cultured man" any more than every man can be a successful tight-rope walker or a successful ventriloquist. There are certain personal aptitudes that come into play in the field of culture as elsewhere and we should do well to remember the distinction of the ancients between "natura" and "doctrina."

Professor Rugg presents his idea of the cultured man by giving some of the "characteristic objects of his allegiance." Briefly they are as follows: the integrity of his own self; the concept of "live and let live"; the obdurate determination to be happy; the deep-rooted belief in the necessity of frequent communion with others; the necessity for frank, glad compromise; the scientific attitude of mind; the obligation to contribute to the carrying on of political and social life of the community and nation; the concept of growth do the passing years produce a more comprehensive, tolerant understanding of life?

In all of these divisions there seems to be a vagueness and incompleteness which the ordinary teacher detects in the utterances of the educational theorist. The incompleteness seems due to the fact that man is considered in this book as Aristotle considered him, as a "social animal." This may have been a proper definition of man in the small political units of Aristotle's day but is it enough today? Is there not a great deal more that is necessary? Does not religion play a part in the life of the cultured man? and literature, and music, and the graphic and plastic arts? Does not man exist first and foremost for himself and only secondly for the social group? Will he not, indeed, be a more effective member of the social group if his own abilities and sensibilities are developed to the highest degree for their own sake? Professor Rugg criticizes the literature of the old curriculum because the Iliad and Odyssey are out of date and do not contribute to the understanding of modern social and political problems. Is beauty ever out of date? Can the humanity of the twenty-fourth book of the Iliad ever be out of fashion? It is the over-emphasis on the social as opposed to the individualistic aspects of education that makes one wonder whether the educational theorists are looking in the right direction for their reforms. It was in the early years of the twentieth century that the old disciplines, Greek, Latin, pure mathematics, began to disappear from American education, to be supplanted largely by the social sciences. And yet never has there been such universal ignorance of economic, racial, and political problems as in the period from the Treaty of Versailles to the present moment. Or if ignorance is not the correct word then there has been -willful disregard of the principles of these sciences, which is a more serious charge than that of ignorance.

Whatever value this review may possess lies in the fact that it is written from the point of view of one who holds that the value of the modern, highly socialized education is problematical at best. The writer questions some of the characteristic objects of the cultured man's allegiance. The validity of the concept of progress in a philosophy of history is clearly open to question. One wonders whether the devastating scepticism of Henry Adams is not as characteristic of the cultured man as a Pippa-like determination to be happy.

It is clear from this review that there is much of a controversial nature to be found in Professor Rugg's book. Both teachers of a conservative type in educational matters, like the present writer, and those who, from wide knowledge of the social sciences, are more progressive in their pedagogical views will find much to inform and interest them.

"Strife," says Heraclitus, "is the father of all things."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

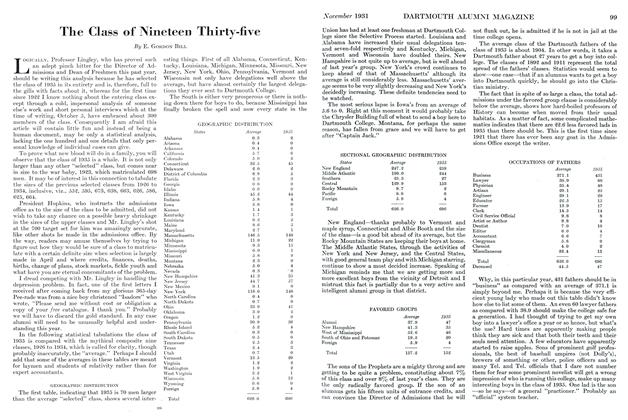

ArticleThe Class of Nineteen Thirty-five

November 1931 By E. Gordon Bill -

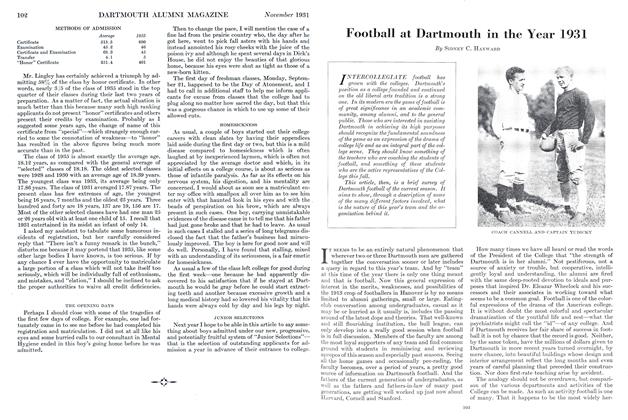

Sports

SportsFootball at Dartmouth in the Year 1931

November 1931 By Sidney C. Hayward -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1910

November 1931 By "Hap' Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1930

November 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1926

November 1931 By J. Branton Wallace -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1929

November 1931 By Frederick William Andres

Books

-

Books

BooksSoiled Pinstripes

October 1979 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN JAPAN AND THE ORIENT INCLUDING HONG KONG, MACAO, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES.

JUNE 1964 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Books

BooksFOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: CAREERS IN PUBLIC RELATIONS.

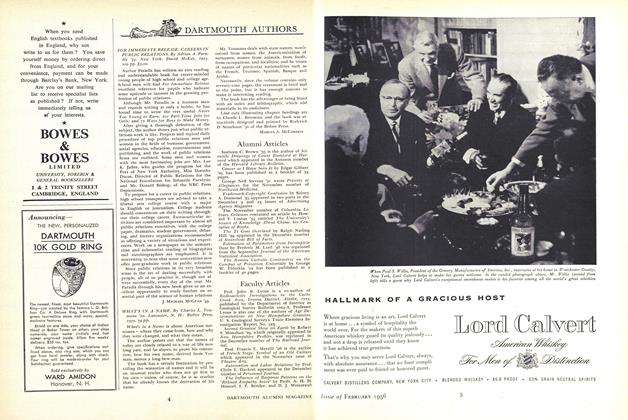

February 1956 By J. MICHAEL MCGEAN '49 -

Books

BooksTHE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS.

NOVEMBER 1967 By MAJOR ERIC H. WIELER, USMC -

Books

BooksCredit to the Age

June 1976 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksTHE ANATOMY LESSON AND OTHER STORIES.

July 1957 By ROBERT Y. TURNER