PROFESSOR Howard M. Jones, writing in the summer issue of the Yale Review, implies that possibly there is a too ostentatious parade of the inferiority complex from which professors in our colleges and universities suffer or say they do. Starting with the admission that American periodicals are largely devoted at present to proving that our higher institutions of learning are in a state of complete chaos. Professor Jones marvels that nobody finds fault with the educational system, or with the professors, quite so acidly as do the professors themselves, in sardonic articles bewailing what is announced as their own abysmal failure, if failure there be. Is it possible that professors really think as meanly of their own work as their despairing outgivings might imply?

It is pointed out that dentists speak rather comfortably of their art, although concerned for the unethical conduct of the few. Physicians, lawyers., engineers, architects—although likewise condemning the occasional charlatan in their ranks—do not reveal any widespread conviction that their professions labor in vain. It is chiefly the college professors who lack esprit decorps, or pride in their calling. This one concludes from reading the words of their mouth and the meditations of their heart as set forth in current magazines. College education is treated as if it were an unholy mess, which results in about everything but real education. If outside reformers and radically disposed students criticize the teaching, as undoubtedly they do, they are occasionally outstripped in acidity by the teachers themselves in criticism of their own cult. So, at all events, it appears to Professor Jones, who holds a brief for the despised professor and who would sound a clarion call to a better estimate of a hard-working, often brilliant, body of experts by those experts themselves. It is meet to confess one's sins when one is conscious of them; but it is insisted that there is such a thing as being righteous overmuch.

This writer evidently believes that the admitted shortcomings of higher education are not justly attributed to the wholesale incompetence of professors, who actually are doing as good a job as circumstances allow, but should be ascribed to the circumstances which allow nothing better. Boys and girls of eighteen to twenty-two will be boys and girls, no matter how you fix it especially when they go to college in droves, as they do now—and adult men of forty and fifty must do the best they can to interest such in the intellectual life, which, one should remember, was probably regarded with much the same indifference by those same professors when they were eighteen.

If one harks back to the colleges of half a century or more ago, one must remember that there were then infinitely fewer students and similarly fewer professors. Among the latter the great figures stand out and can be seen in their true grandeur today by reason of perspective; yet the average old-time college teacher, compared with the average modern college professor, "was a badly trained, miseducated man" in the opinion of Professor Jones; and there was "an unreality, a narrowness, and lack of depth" in the college curriculum, accompanied by a "total lack of understanding of adolescence," by contrast with what exists today. Yet, curiously enough, one heard less then of the failure of higher education to educate than one hears now. Perhaps the problem is best summed up in the phrase (which the writer quotes) asserting that the essence of it is produced by the "undergraduateness of undergraduates," rather than by any deficiency in the faculties, or the curricula, or the equipment.

The first duty of the teacher is to teach and that of the learner is to be willing to learn, no doubt. Possibly we shall go farther and faster if we revert to such fundamental principles and let our emotional enthusiasms go. The extra-curricular activities of professors may be as well worthy our consideration as the extra-curricular activities of students, as hindering their effectiveness on the job. That they are capable of effectiveness, and measurably attain it, we prefer to believe, despite professorial jeremiads born of the delusion that doing the impossible alone can justify college teaching.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

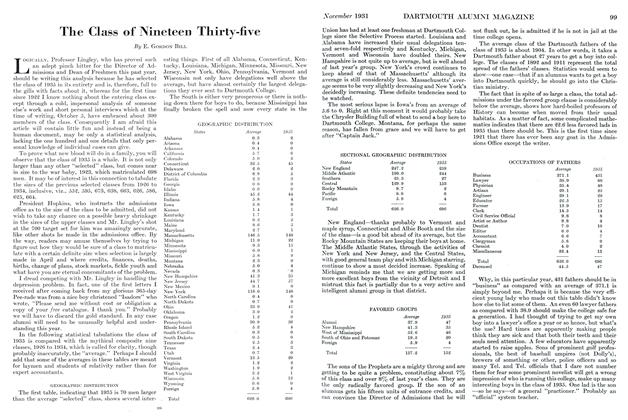

ArticleThe Class of Nineteen Thirty-five

November 1931 By E. Gordon Bill -

Sports

SportsFootball at Dartmouth in the Year 1931

November 1931 By Sidney C. Hayward -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1910

November 1931 By "Hap' Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1930

November 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1926

November 1931 By J. Branton Wallace -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1929

November 1931 By Frederick William Andres

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE WINTER CARNIVAL

March 1912 -

Article

ArticleLIST OF THOSE CHOSEN FOR FRENCH SCHOLARSHIPS

May 1920 -

Article

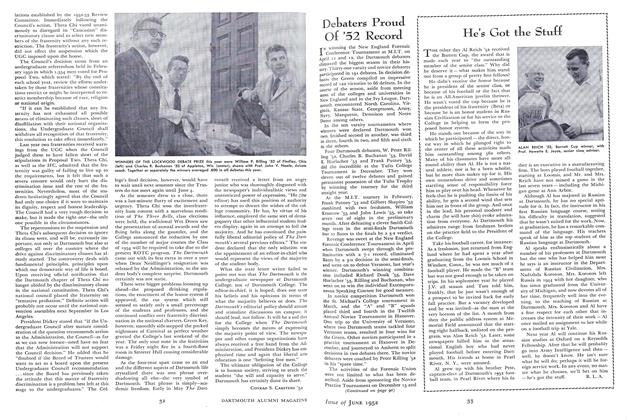

ArticleDebaters Proud Of '52 Record

June 1952 -

Article

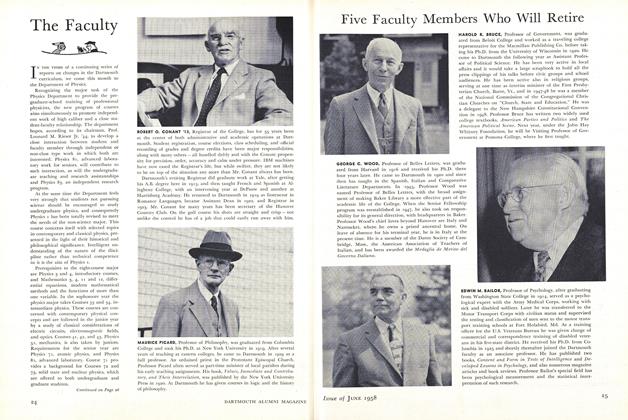

ArticleFive Faculty Members Who Will Retire

June 1958 -

Article

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

April 1940 By Hans Paschen '281. -

Article

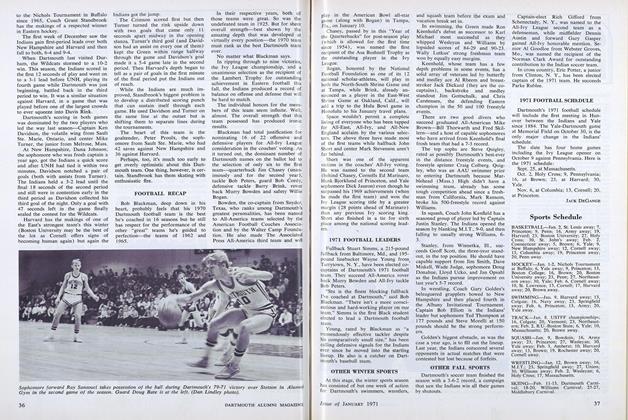

ArticleFOOTBALL RECAP

JANUARY 1971 By JACK DEGANGE