THEY'RE JUST A LOT of pictures to me and I don't believe they mean anything to four out of five of the fellows around here" was the statement overheard a few days ago in the Reserve Room of Baker.

While there are undoubtedly some undergraduates who have scarcely given the frescoes a second thought since their first puzzled glance at the grotesque figures of the migrating Toltecs, it is fairly certain that the above statement does not represent campus opinion. For, though undergraduate interest in the frescoes has in many cases been only mild, and in others only a matter of curiosity, the two years' work of the Mexican artist that stretches around the walls of the Reserve Room has meant something to a majority of the undergraduate body.

The position of the frescoes themselves has been their main advantage in catching undergraduate attention. Being painted on the walls of the room where some five hundred men must pass every day, it has been impossible for them to fail to attract interest. Most of that interest, it is true, started out as mere curiosity at the strange and highly colored figures and images that took shape where only blank walls have been before, but as the painting progressed before our eyes, as the evolving theme seemed to show more and more that there was something new and something of unusual significance behind it all, and as discussion and explanation of the frescoes came to reach more people, then that first curiosity turned to interest, and the interest to enthusiastic endorsement or sharp criticism of the work.

To some groups of students and some individuals the frescoes have, of course, carried far greater interest and influence than to others. Especially to those taking courses in the art department have they been of definite usefulness. There are almost a hundred and fifty students carrying art courses this year, and the presence in Hanover of one of the greatest of modern fresco artists engaged in his most momentous work to date has offered a rare advantage in the dovetailing of classwork and study of an unfolding epic. Professor Artemas Packard of the art department, who was instrumental in bringing Orozco to Dartmouth and who followed the project from its start to finish, has found members of his classes taking unusual interest in the study of the frescoes. "The project," he has stated, "has enormously simplified some of the most difficult problems which confront the teacher of art. It has brought out into the open, on the level of common everyday discussion, matters which have been hitherto confined to the rarified atmosphere of the classroom and to the polite mumbo-jumbo of the salon and the teatable."

In other subjects too have the frescoes been found to be a timely supplement to the regular assignments, especially in those sociology courses where the study of Gruening and Chase's books on Mexico deal at some length with the culture of the Toltec and Aztec tribes.

THE FRESCOES HAVE furnished a fertile field of discussion for undergraduates with would-be professional interest in art, and the comments and criticisms of Orozco's technique—his orchestration and the emphasis upon two-dimensional form and verticality—have only been matched on the other side by the discussions of the self-styled "intellectuals" over the social and economic interpretations of the paintings.

The interest of the average undergraduate in the frescoes has been a more passive one. He may like them because he recognizes a great work, or he may not like them because he thinks they are ugly, but he will not come away over- whelmed with feeling by an epic that explains on plastic walls the abuses of the modern world, nor is he filled with indignation at "Communistic propaganda." Rather, with his attention attracted first by curiosity in a type of art foreign to his experience and by actually witnessing the artist at work, the average undergraduate became more interested, and by observation and chance discussion obtained some idea of the meaning behind the brilliant colors. Not only has the newness and difference of this work added to the display of interest, but also the fact that "the Epic" is a definite departure from the "art for art's sake" idea and a return to the conception that art can be for the many—that it can be utilized as a medium for expressing one's ideas about war, education, and present day political and social conditions.

That Dartmouth students are rather proud of the frescoes can be seen by the way they exhibit them to their visitors in Hanover. The Tower Room, since the completion of the Library the number one show-off place in Baker, has yielded its position to the Reserve Room. This Carnival probably saw more guests taken to the Library in one weekend than at any time in the last five years.

COMMENTS AND CRITICISMS of the frescoes heard in undergraduate conversations cover a wide and varied field. The main complaint seems to rest with the subject of the frescoes. "Why did Orozco devote one-half of his space to a consideration of an Indian culture with which we are unfamiliar?" "Why did he, in a New England college, depict the rise and fall of a civilization that has had so little influence upon our own?"

After the information was given out that one or two of the last panels were to be given over to Eleazar's pioneer movement into the North country many were disappointed when the artist changed his mind and substituted totem poles and a laborer at leisure reading. There was the impression that Orozco slighted the final panels. Someone was heard to remark, "He must have gotten tired painting after those two years, he certainly whipped through those last panels."

At the testimonial banquet given to Orozco by the Junto February 16, Louis Mumford refuted the contention that the frescoes were anomalous to the atmosphere of Dartmouth College and New England, and, expressed his opinion that "The real New England is not made up of hooked rugs and wayside shops. The real New England is progressive in spirit. Nothing human can be foreign to it." Some, however, find it difficult to connect New England with Toltecs' seeking new watering places and Quetzalcoatl's eclipsing the Fire God astride the Pico de Orizaba.

Many find fault with the ugliness and brutalness with which the frescoes are carried out. "Those Indians are apportioned atrociously." "Those little schoolgirls look like morons." Answering arguments point out, however, that Orozco is an expressionist—that he is drawing ideas, not pictures. Professor Packard says, "Every form, every line, every color, every suggestion of movement is chosen and arranged for the purpose not of revealing what things look like but what they feel like, what they mean emotionally. The camera has long since released the painter from the business of imitating nature."

FROM SOME SOURCES the frescoes are frowned upon for their "Communistic propaganda." One undergraduate, the son of a New York manufacturer, thinks the Dartmouth library is no place for the frescoes. He says one of his professors told his class Orozco was a communist and that the frescoes were merely "red" propaganda against the present social and economic setup.

In an interview with The Dartmouth Orozco explained that his Communism was simply a doctrine, without definite methods. He, like Christ and Gandhi, believes in a universal brotherhood of man and in justice to all men. He is no adherent to the present Communistic party. And it seems to be the general opinion that he did not let the message of his art degenerate into poster propaganda.

The cartoon panel showing the unknown soldier covered with nationalistic emblems and cheap wreaths seems to receive less criticism than most of the other panels. International warfare has few adherents at Dartmouth.

The panel depicting modern education as a skeleton giving birth to other stillborn skeletons with the mid-wifery per- formed by a gowned professor comes in for its share of abuse, but, strangely enough, most of it from alumni rather than from present undergraduates. Letter after letter has come to President Hopkins resenting that such a painting be placed within the halls of this educational institution. Modern youth in the Hanover man factory, however, passes smugly by the skeleton, perhaps to stop at the totem poles and ask why Eleazar was not included.

MANY INTERESTING SIDEI.INES and stories have come out of the frescoes. One is the game of picking out personages from the figures drawn on the panels. Quite a bit of studying has been done on the masked features of one of the professors standing over the skeleton, and several majors claim him as theirs. The story is told of Orozco's being asked if the figure of the Mexican peon in the panel of rebel Latin America represented Villa. "Pancha Villa?" he retorted, "No, certainly not. It is President Hopkins, you, me, anyone. It is a type, not an individual."

In the panel showing American independence and order there is a square of grain in the lower left hand corner. One half of the grain is golden, the other a greenish hue. It is explained that Orozco ran out of one of the paints before he filled in all the grain, and when it was suggested that he change all to one color, replied, "No, that's unimportant."

Some good New Englanders regret the artist's never having attended a New England town meeting. In his picture of a town meeting the men are all wearing their hats.

The influence and effect of the Orozco upon Dartmouth College and upon her men is of a quantity difficult to measure. It is certain though that Senor Orozco is one of the greatest of fresco artists since the Renaissance, that here at Hanover he has completed his greatest and most significant work, and that the value of that work will be realized only with the passing of time. Dartmouth is fortunate to have had Orozco.

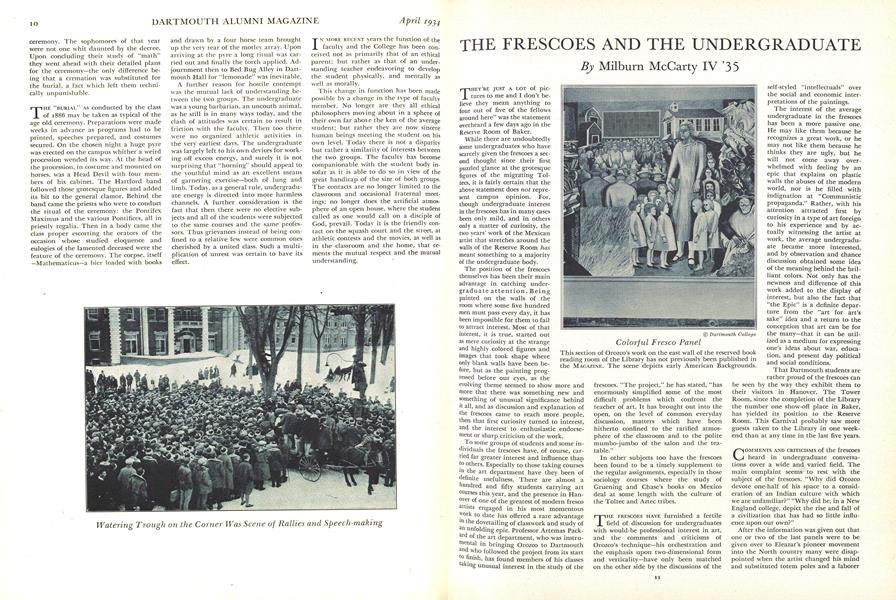

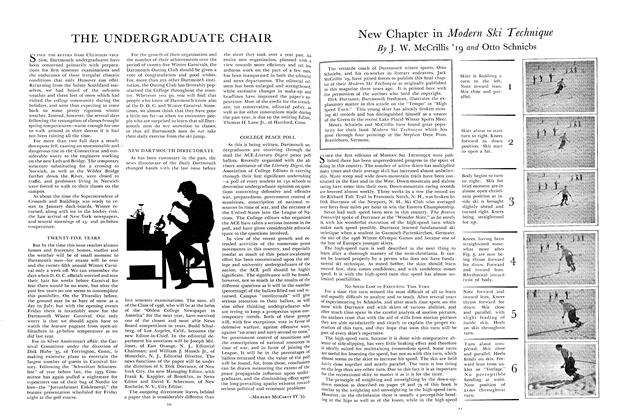

Colorful Fresco Panel This section of Orozco's work on the east wall of the reserved book reading room of the Library has not previously been published in the MAGAZINE. The scene depicts early American Backgrounds.

As the Spectator Sees the East Wall Including the striking portrait of Hernan Cortez embarking on his conquest of Mexico, after burning his Spanish ships behind him. The much-discussed "academic panel" is shown as the last in this series of murals.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

April 1934 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

April 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

April 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

April 1934 By Laurence W. Griswold -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

April 1934 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

April 1934 By John C. Allen

Milburn McCarty IV '35

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1934 By Milburn McCarty IV '35 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

December 1934 By Milburn McCarty IV '35 -

Article

ArticleMILESTONES

December 1934 By Milburn McCarty IV '35 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

January 1935 By Milburn McCarty IV '35 -

Article

ArticleON THE DARTMOUTH STAGE

January 1935 By Milburn McCarty IV '35 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1935 By Milburn McCarty IV '35

Article

-

Article

ArticleROBINSON HALL

June, 1914 -

Article

ArticleHeads Committee

October 1938 -

Article

Article217 Rare Volumes In Gift to Library

February 1950 -

Article

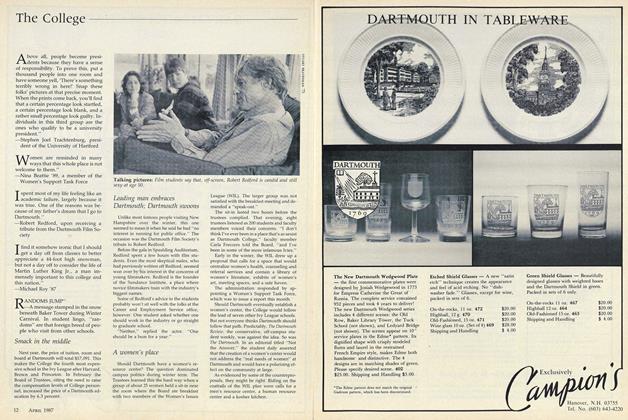

ArticleLeading man embraces Dartmouth; Dartmouth swoons

APRIL • 1987 -

Article

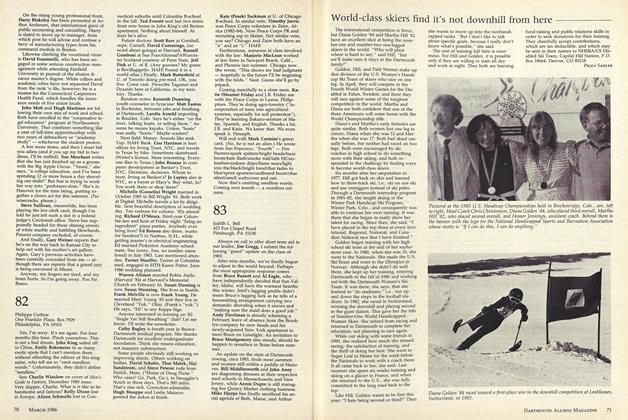

ArticleWorld-class skiers find it's not downhill from here

MARCH • 1986 By Peggy Sadler -

Article

ArticleThe Review's Competition

MAY 1989 By Sarah B. Meyers