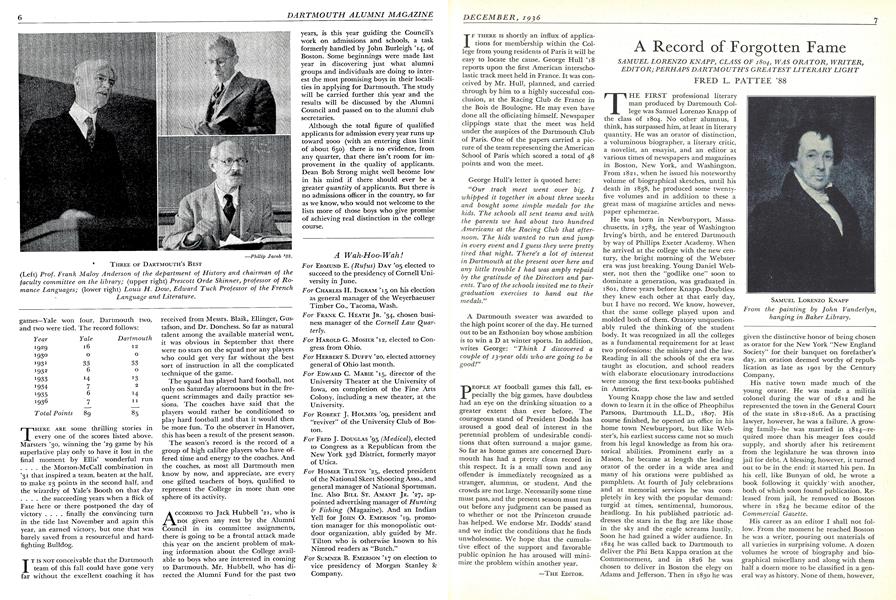

SAMUEL LORENZO KNAPP, CLASS OF 1804, WAS ORATOR, WRITER,EDITOR; PERHAPS DARTMOUTH'S GREATEST LITERARY LIGHT

THE FIRST professional literary man produced by Dartmouth College was Samuel Lorenzo Knapp of the class of 1804. No other alumnus, I think, has surpassed him, at least in literary quantity. He was an orator of distinction, a voluminous biographer, a literary critic, a novelist, an essayist, and an editor at various times of newspapers and magazines in Boston, New York, and Washington. From 1821, when he issued his noteworthy volume of biographical sketches, until his death in 1838, he produced some twenty-five volumes and in addition to these a great mass of magazine articles and newspaper ephemerae.

He was, born in New buryport, Massachusetts, in 1783, the year of Washington Irving's birth, and he entered Dartmouth by way of Phillips Exeter Academy. When he arrived at the college with the new century, the bright morning of the Webster era was just breaking. Young Daniel Webster, not then the "godlike one" soon to dominate a generation, was graduated in 1801, three years before Knapp. Doubtless they knew each other at that early day, but I have no record. We know, however, that the same college played upon and molded both of them. Oratory unquestionably ruled the thinking of the student body. It was recognized in all the colleges as a fundamental requirement for at least two professions: the ministry and the law. Reading in all the schools of the era was taught as elocution, and school readers with elaborate elocutionary introductions were among the first text-books published in America.

Young Knapp chose the law and settled down to learn it in the office of Pheophilus Parsons, Dartmouth LL.D., 1807. His course finished, he opened an office in his home town Newburyport, but like Webster's, his earliest success came not so much from his legal knowledge as from his oratorical abilities. Prominent early as a Mason, he became at length the leading orator of the order in a wide area and many of his orations were published as pamphlets. At fourth of July celebrations and at memorial services he was completely in key with the popular demand: turgid at times, sentimental, humorous, headlong. In his published patriotic addresses the stars in the flag are like those in the sky and the eagle screams lustily. Soon he had gained a wider audience. In 1824 he was called back to Dartmouth to deliver the Phi Beta Kappa oration at the Commencement, and in 1826 he was chosen to deliver in Boston the elegy on Adams and Jefferson. Then in 1830 he was given the distinctive honor of being chosen as orator for the New York "New England Society" for their banquet on forefather's day, an oration deemed worthy of republication as late as 1901 by the Century Company.

His native town made much of the young orator. He was made a militia colonel during the war of 1812 and he represented the town in the General Court of the state in 1812-1816. As a practising lawyer, however, he was a failure. A growing family—he was married in 1814—required more than his meager fees could supply, and shortly after his retirement from the legislature he was thrown into jail for debt. A blessing, however, it turned out to be in the end: it started his pen. In his cell, like Bunyan of old, he wrote a book following it quickly' with another, both of which soon found publication. Released from jail, he removed to Boston where in 1824 he became editor of the Commercial Gazette.

His career as an editor I shall not follow. From the moment he reached Boston he was a writer, pouring out materials of all varieties in surprising volume. A dozen volumes he wrote of biography and biographical miscellany and along with them half a dozen more to be classified in a general way as history. None of them, however, are alive today. As a biographer he was too eulogistic, too ornate in his style, too lacking in plan and concentration. "His pages" says one critic, "glow with the patriotism of the Jacksonian era." His Sketches of Distinctive Americans is full of interesting anecdotes not elsewhere recorded, and also rich in spots in personal reminiscences.

His two collections of short stories, Tales of the Garden of Kosciuszko, 1834, and The Bachelors, and Other Tales, 1836, are distinctive when compared with the meager short-story product of the early thirties, though not worth republishing to-day. But for three of his volumes Knapp deserves great credit, especially in the area of his alma mater. His first published volume, Letters of Shahcoolen, bears on its title page the date 1802. The fourteen letters after the model of Montesquieu and Goldsmith purport to have been written by a Hindu Philosopher, travelling in the United States and sent to friend El Hassan in Delhi. Written, presumably on the Dartmouth campus during his junior year or earlier, they had found publication in the New York Commercial Advertiser, and then to the author's surprise had found a publisher in Boston. Sophomoric in every paragraph, "Steered in juvenile solemnity," yet the little book still has value. It is a sketch-book of American manners and scenery and morals as seen from a Dartmouth window by an undergraduate. For women's rights as demanded by Miss Woolstonecraft the young student has supreme contempt:

"In America, although the women arebeautiful as the sun, with complexions resembling the first blushes of the morning,and persons as graceful as the poetical sisters, who wander in the spicy groves ofMath'ura, still, the new philosophy has induced them, in many instances, to exposetheir persons in such a manner, as to excitepassion, and to extinguish respect."

Two of his letters present a short history of American poetry, perhaps the first attempt at a history of American literature. Our poetry he finds to be merely an echo of English verse. Public taste, he declares, "did not encourage the cultivation of poetry."

"Party-spirit and the lust of gain, rulethe American nation with such undividedsway, as to engross every passion, and inlistevery propensity. The meanest man is apolitician, equally with the greatest, andfeels as if 'the weight of mightiest monarchies' were to be sustained upon hisshoulders." Aside from Freneau and Livingstone, he reviews only the poetry of Dwight, Trumbull, Barlow, and Humphries. Not much American poetry in 1802.

But in 1829 appeared his fuller study of the American literary and artistic background, his volume, Lectures of AmericanLiterature, the first book of its kind to appear in America. Dartmouth College should be proud to have produced the two earliest pioneers in what has become an important field: Samuel L. Knapp and Charles Francis Richardson. In 1829 American Literature was a tiny rill as compared with its volume to-day, but Knapp studied its fountain heads in American history and in the American philosophical evolutions, and worked out a plan of study greatly suggestive to later workers. One more volume of Knapp's deserves more than passing notice, his Advice on thePursuits of Literature, undoubtedly the first practical text-book on English literature published in America. Dedicated to the members of the New York Mercantile Association, it was intended for the instruction of persons engaged in business and it was for a long period widely used. In the words of Duyckinck: "It contains a brief review of the leading English authors from Chaucer to thepresent time, with occasional extracts, anda concise survey of European history, asconnected with literature and the progressof learning from the days of Homer to thesettlement of the present United States."

A summer home he established in his last years at Sanbornton, N. H. [see Runnel's History of Sanbornton (1881). See also George Harvey Genzmer's History ofNew buryport]. His death in 1838 at the comparatively early age of 55 cut short at the heights of his literary productivity a vigorous writer, in a period that could ill spare his gifted pen.

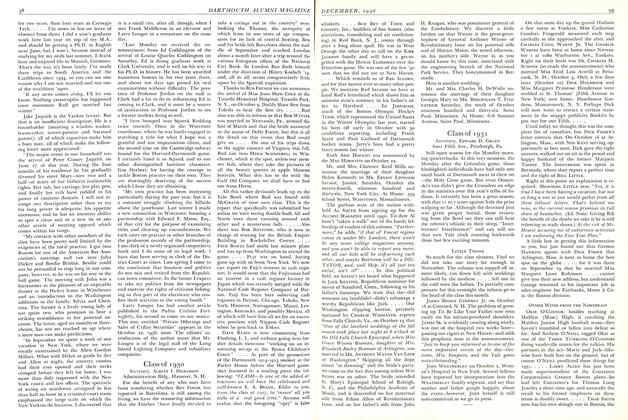

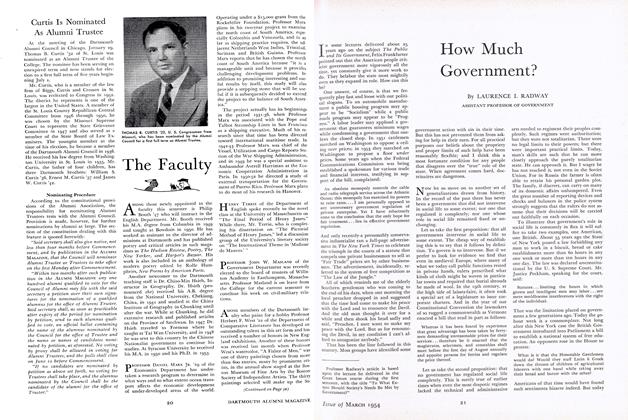

SAMUEL LORENZO KNAPP From the painting by John Vanderlyn,hanging in Baker Library.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsFollowing the Big Green Teams

December 1936 By ROBERT P. FULLER '37 -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

December 1936 By The Editor -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

December 1936 By Prof. Nathanie. G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1931

December 1936 By Edward D. Gruen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

December 1936 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

December 1936 By F. Willian Andres

FRED L. PATTEE '88

Article

-

Article

ArticleC. F. RICHARDSON'S TRIBUTE TO THE GREAT PRESIDENT

DECEMBER 1926 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI COUNCIL MEETS IN BOSTON

DECEMBER 1926 -

Article

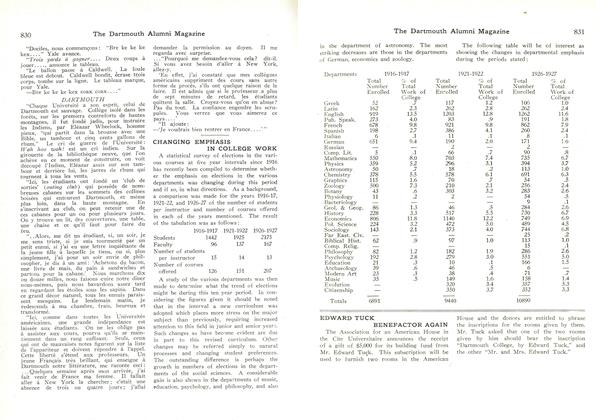

ArticleCHANGING EMPHASIS IN COLLEGE WORK

AUGUST, 1928 -

Article

ArticleRetiring Professors

June 1975 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

March 1954 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Article

ArticleTimothy Edgar ’94

MAY | JUNE By LISA FURLONG