Norfolk Prison Books

To the Editor:

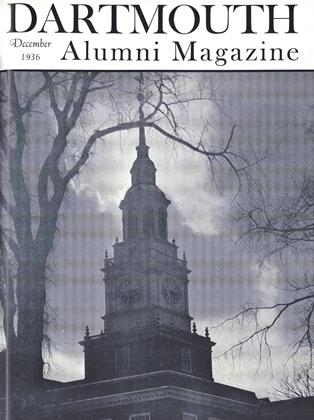

I returned safely from a most enjoyable week-end at Hanover, and finished in the evening reading the November number of the MAGAZINE, which I think is one of the very best that you have ever put out. I think the cover picture of the gymnasium is perhaps the best of all. There are so many interesting articles in this number that I won't attempt to mention them except to say I enjoyed them all. I noticed in reading Professor West's interesting article on what books to read, that he refers to a catalogue of the books which I gave to the Norfolk State Prison Colony, and he expresses some doubt whether I have any extra copies that anyone desiring one could obtain. I wish to say that I have a large number of these and would be glad to send them to anyone who is interested, without charge, if they would give me their address. I am sending a copy to you thinking perhaps you have not seen it.

75 Ashburton Place,

Boston, Massachusetts,

November 9, 1936.

Fraternities a Liability

To the Editor:

In view of the discussion regarding Dartmouth fraternities, the comment of a non-fraternity alumnus may be of interest. From the viewpoint of nearly a quartercentury out of college I think I can consider the fraternity question fairly and dispassionately. My opinion is actuated by no feeling of rancor or resentment. I received a fraternity bid, and have the friendliest feelings for fraternity men as a class. I do not believe that fraternities are helpful to college spirit or conducive to that democracy and brotherhood which we love to associate with Dartmouth. On the contrary. From the standpoint of the greatest good to the student body as a whole, Dartmouth in my opinion would be better off without fraternities. I say this fully appreciating the good that fraternities have done to many boys, the social and personal advantages of membership, etc. The great trouble as I see it is that these advantages accrue exclusively to a selected group who deserve them no more than the non-fraternity men; and the often bitter feeling of being considered inferior common among many boys left out of the fold. Take the boy who enters Dartmouth knowing no one, with no fraternity connections, who is not athletic or the son of a well-to-do or prominent man: who is quiet and retiring—not a "mixer." No matter how much excellent stuff there may be in him, what chance has he to make a fraternity? A mighty slim one—at least in my day. College men, being young, naturally judge largely by external superficialities. The hail-fellow-well-met, the athlete, the chap with connections, the showy fellow with an ingratiating manner or other shallow attributes that win popularity, is the one sought after. In many cases, as I think fair-minded fraternity alumni will admit, this works very unjustly. STAMPED AS INFERIOR The boy passed over, if he has any pride and considers himself as good as the next fellow, is apt to feel humiliated and hurt. His fellows have stamped him with the stigma of inferiority. Particularly does this rankle when he sees so many empty "fourflushers" welcomed into the select circle. And unfortunately this feeling is sometimes accentuated by the attitude of indifference or patronizing superiority consciously or unconsciously assumed by some fraternity members toward the chap with no pin on his vest. Naturally, the fraternity men tend more and more to draw apart in a select world of their own. The non-fraternity men are left more or less to their own devices. They or many of them—feel left out in the cold they just "don't belong." They are the forgotten, ignored under-dogs of college life. In many cases, this wounds deeply. Is this feeling helpful to democracy? Does it help make a more loyal and enthusiastic Dartmouth man of the fellow who feels unjustly deprived of the choicest social and personal associations of college life?

It is no answer, as I see it, to say that men naturally tend to form groups and that if there were no fraternities such groups would still form. For the secret fra- ternal bond, the display of distinguishing insignia, the exclusiveness of the fraternity house and its associations, the clannishness that the fraternity engenders, cause more envy and wounded feelings than would mere division into loosely knit informal groups.

I could elaborate this theme further, but I have said enough to indicate why I be- lieve that considered from the standpoint of college democracy and brotherhood, the fraternity is a liability to Dartmouth Spirit.

Marblehead, Massachusetts,November 16, 1936.

Love of Dartmouth

To the Editor:

It may be of interest to alumni to read the following letter, evidence of the affection for the College existent in groups outside of the alumni.

Acting Supervisor of Athletics.

State Prison,

"Dear Mr. McCarter:

"Just a few lines to thank you for the'Football' you gave us a few weeks ago. Wereally appreciate it very much, and I wishto say now that nine out of ten of the inmates are pulling for 'Dartmouth' this year,today Deputy Warden Knight, who is areal fellow, set up a 'Radio Set' so that allcould hear the Dartmouth vs. Yale game.Those who were pulling for Yale sure didget the old razz when the game was over,again a thousand thanks for the 'Ball'."

"Squash" and "Tony"

To the Editor:

In September, 1893, when I rode up the hill in the old horse-driven stage coach from Norwich station, at the beginning of freshman year, the first persons I met were Charles Sherman Little '91, Medical College '96, and George Huff, Medical College '96. Charles Sherman Little was known as "Squash" and George Huff as "Tony," but someone else will have to say how they received their Dartmouth nicknames. Those two roomed together in the Deke Annex, where the Freshmen Commons now is, west room, third floor, and were historic characters in Dartmouth athletics (Medics could play on teams up to the fall of '95). They became distinguished in their respective spheres after leaving college. Both died recently, "Squash" in June and "Tony" in September, 1936.

You always pick someone older and ahead of you in college as your college hero, and "Squash" was my great Dartmouth hero. I played with him on the '93 and '94 elevens. Little captained the '94 eleven and I succeeded him as captain. "Squash" was a deadly earnest spirited player, and many attempted to imitate him. He played tackle, was over six feet and, at that time, stripped about 185 pounds. His great forte was to break through and get the ball carrier behind the line. In my time, 1893 to 1897, he was the great personality in Dartmouth football and his spirit and wellbalanced judgment influenced the College for many years after he left. His distinguished career after leaving College was covered in the October issue of the ALUMNIMAGAZINE.

George Huff entered Dartmouth Medical College the fall of 1893 from the University of Illinois. Ed Hall '92 coached all Illinois teams the year after he graduated, 1892 and 1893, and through his influence, Huff came to Dartmouth. Huff played guard on the '93 and '94 elevens and first base on the ball team, which he captained in 1894. He was given the captaincy the first year he was in college because of his experience and ability.

Huff returned to Illinois in 1895 and began a career in constructive athletic administration. He coached Illinois in football and baseball for several years but soon gave up coaching football for his first lovebaseball. He felt that he was not a fully qualified football coach and that weakness in this line would interfere with his efficiency as a baseball coach. He became an outstanding baseball coach, producing many champion teams as well as big league ball players. He became director of athletics in 1901, and director of physical welfare in 1924. With the establishment of the school of education in 1932 he became director, overseeing physical education for men and women, and guiding intercollegiate and intramural athletics and the health service.

It was Huff who first declared that coaches of competitive sports should be trained for their work just as men in other professions. In 1914 he established a summer course for coaches, the first of its type, as those already in existence emphasized physical education proper and gave practically no attention to competitive sports. His next step, considered revolutionary at the time, was to establish a four-year course in coaching and physical education in 1919 with a degree for graduates. The first class was graduated in 1923. Huff was not only a constructionist, but a practical (not visionary) idealist, and his death brought to a close a life distinguished not only by achievement, but by adherence to a fine code of sportsmanship, insisting as he did on the strictest observance of western conference rules. His theory was that if a college does not aim toward ideals no one else will and colleges should lead. As an idealist, he championed amateurism, was an unyielding foe of wagering on athletic contests, particularly college football, and led the drive to eliminate drinking among football spectators.

Sentiment for Dartmouth and Dartmouth men remained with Huff to the end, and the influence of Dartmouth on him, it is believed, was considerable. Ed Hall, our great athletic administrator and practical idealist, was, for many years, in close personal contact with Huff. Both had similar thoughts, and worked on the same problems. Hall's influence on Huff was an early and I believe a lasting one.

Considering both Little and Huff—if you were to state what were the typical characteristics of each, you could say that "Squash" was spirited and sympathetic and "Tony" was sturdy, steady and idealistic. The interesting thing, outside of their accomplishments, is that they roomed to- gether, were both on the same teams, were captains, and were warm friends at Dartmouth.

1 North LaSalle Street,

Chicago, Illinois.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsFollowing the Big Green Teams

December 1936 By ROBERT P. FULLER '37 -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

December 1936 By The Editor -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

December 1936 By Prof. Nathanie. G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1931

December 1936 By Edward D. Gruen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

December 1936 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

December 1936 By F. Willian Andres