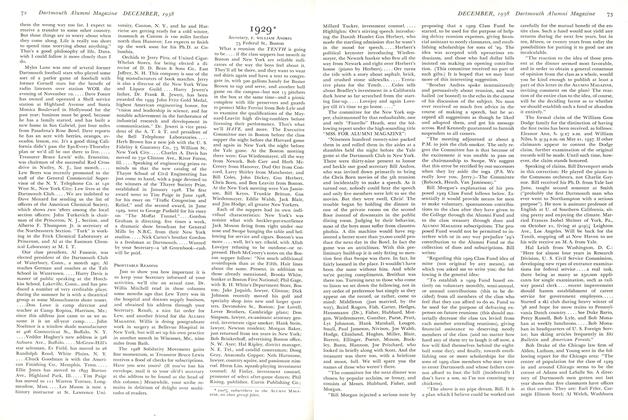

BASIL O'CONNOR ' 12 IS A NUMBER ONE DARTMOUTH FAN, WIN OR LOSE

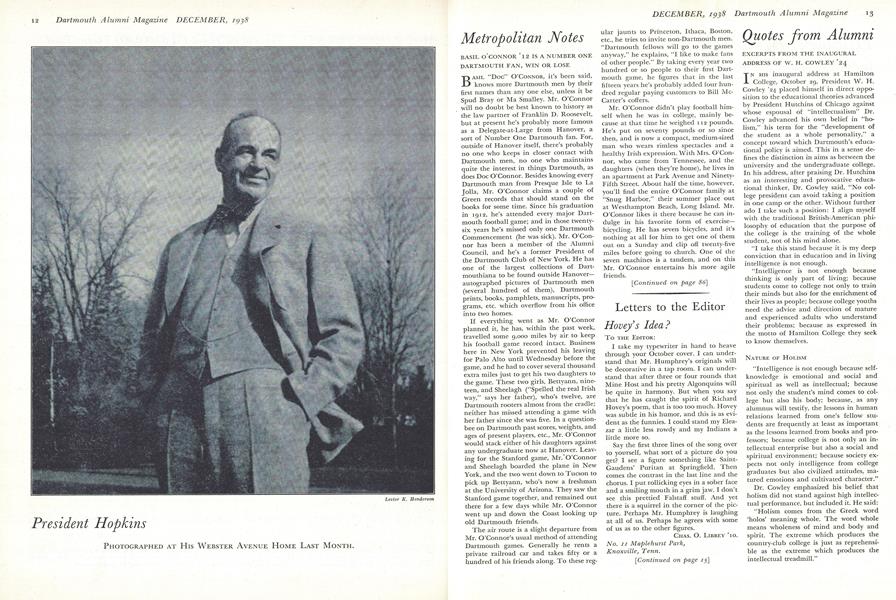

BASIL "DOC" O'CONNOR, it's been said, knows more Dartmouth men by their first names than any one else, unless it be Spud Bray or Ma Smalley. Mr. O'Connor will no doubt be best known to history as the law partner of Franklin D. Roosevelt, but at present he's probably more famous as a Delegate-at-Large from Hanover, a sort of Number One Dartmouth fan. For, outside of Hanover itself, there's probably no one who keeps in closer contact with Dartmouth men, no one who maintains quite the interest in things Dartmouth, as does Doc O'Connor. Besides knowing every Dartmouth man from Presque Isle to La Jolla, Mr. O'Connor claims a couple of Green records that should stand on the books for some time. Since his graduation in 1912, he's attended every major Dartmouth football game; and in those twenty-six years he's missed only one Dartmouth Commencement (he was sick). Mr. O'Connor has been a member of the Alumni Council, and he's a former President of the Dartmouth Club of New York. He has one of the largest collections of Dartmouthiana to be found outside Hanoverautographed pictures of Dartmouth men (several hundred of them), Dartmouth prints, books, pamphlets, manuscripts, programs, etc. which overflow from his office into two homes.

If everything went as Mr. O'Connor planned it, he has, within the past week, travelled some 9,000 miles by air to keep his football game record intact. Business here in New York prevented his leaving for Palo Alto until Wednesday before the game, and he had to cover several thousand extra miles just to get his two daughters to the game. These two girls, Bettyann, nineteen, and Sheelagh ("Spelled the real Irish way," says her father), who's twelve, are Dartmouth rooters almost from the cradle; neither has missed attending a game with her father since she was five. In a questionbee on Dartmouth past scores, weights, and ages of present players, etc., Mr. O'Connor would stack either of his daughters against any undergraduate now at Hanover. Leaving for the Stanford game, Mr.'O'Connor and Sheelagh boarded the plane in New York, and the two went down to Tucson to pick up Bettyann, who's now a freshman at the University of Arizona. They saw the Stanford game together, and remained out there for a few days while Mr. O'Connor went up and down the Coast looking up old Dartmouth friends.

The air route is a slight departure from Mr. O'Connor's usual method of attending Dartmouth games. Generally he rents a private railroad car and takes fifty or a hundred of his friends along. To these regular jaunts to Princeton,. Ithaca, Boston, etc., he tries to invite non-Dartmouth men. "Dartmouth fellows will go to the games anyway," he explains, "I like to make fans of other people." By taking every year two hundred or so people to their first Dartmouth game, he figures that in the last fifteen years he's probably added four hundred regular paying customers to Bill McCarter's coffers.

Mr. O'Connor didn't play football himself when he was in college, mainly because at that time he weighed 112 pounds. He's put on seventy pounds or so since then, and is now a compact, medium-sized man who wears rimless spectacles and a healthy Irish expression. With Mrs. O'Connor, who came from Tennessee, and the daughters (when they're home), he lives in an apartment at Park Avenue and Ninety-Fifth Street. About half the time, however, you'll find the entire O'Connor family at "Snug Harbor," their summer place out at Westhampton Beach, Long Island. Mr. O'Connor likes it there because he can indulge in his favorite form of exercisebicycling. He has seven bicycles, and it's nothing at all for him to get one of them out on a Sunday and clip off twenty-five miles before going to church. One of the seven machines is a tandem, and on this Mr. O'Connor entertains his more agile friends.

Despite the wide range of his friends and interests, Mr. O'Connor has always been slightly shy of the public eye. Several times he has passed up auspicious political opportunities; in 1930, for instance, he begged off when Governor Lehman wanted to draft him for Attorney General of New York State. But feature writers from the newspapers and magazines are now beginning to beat a track to his office, and in the future, whether Mr. O'Connor wishes it or not, he is going to become more and more of a public figure. For, in addition to his own future career as a lawyer (he expects to practice at least twenty-five more years), Mr. O'Connor will undoubtedly come to occupy the same position in relation to Franklin D. Roosevelt as William H. Herndon did in the case of Abraham Lincoln. For years Mr. Herndon's own memory was the favorite source of Lincoln stories, and his recently published letters comprise today the major collection of Lincolniana we have.

Whatever you or I think of our President, he will certainly become one of the most prominent figures of our future history books. Some observers, foreseeing a permanence of much of Roosevelt's social legislation, point out that some day he may rank alongside even Lincoln himself. Opinions on him which are passed out to future high school kids, whatever they may be, are certain to be based in some part upon source material from Doc O'Connor, who was his law partner from 1925 to 1933.

Mr. O'Connor's account of his first meeting with Mr. Roosevelt and of their law partnership, is a rather placid, unexciting story. (Tense, dramatic scenes will have to be supplied later by the movie writers.) O'Connor, after finishing Harvard Law School in 1915 (he was only 23), practiced for a time in New York, in the Oklahoma oil-fields, and in Boston. He returned to New York, and in 1919, at the age of 27, established his own firm. Within a short time he was one of the best known lawyers on oil matters around town. Along about 1921 he first met Mr. Roosevelt. He's not sure of the year, and he's not sure whether it was at a party or at one of the downtown law offices. Roosevelt at the time was doing advisory work for another firm, and he and O'Connor, meeting more and more frequently, became close friends. Late in 1924, as Mr. O'Connor recalls it, they just sort of mutually decided it'd be a good idea to join up, and so on January 1, 1935, the firm of Roosevelt and O'Connor was opened. Everything went along so well that Mr. Roosevelt remained in the firm during his four years as Governor of New York. The law firm, which includes some sixteen lawyers, is now known as O'Connor and Farber.

As he looks back now, Mr. O'Connor is sure he was aware of Roosevelt's destiny, even as early as 1925. "I didn't feel right letting him get law business," O'Connor explains, "for I was sure there were so much more important things ahead of him." He thinks also that Roosevelt was aware of his own destiny. "Most great men are, don't you think?" he says.

Mr. O'Connor is still one of the President's closest friends and advisors. He's a frequent overnight guest at the White House, and Bettyann and Sheelagh, who sometimes accompany him, always call the President "Uncle Franklin." That Mr. O'Connor maintains these relations, in spite of touchy situations such as the Presidential purging of Congressman John J. O'Connor (who is his brother), is just another example of his übiquitous acumen in handling men and things.

When they were law partners Mr. O'Connor used to call Mr. Roosevelt "Frank," but, believing in the dignity of the office, he now addresses him as"Mr. President." The President usually calls him "Doc." Sometimes on state occasions, however, the Chief Executive will say to another White House visitor: "I want you to meet my former law partner, Mr. Ziltch. This isn't Mr. Joe Ziltch, this is Mr. Oscar Ziltch." The passing dignitary occasionally happens to be a newly arrived diplomat who, not yet up on American slang, will in turn take "Mr. Ziltch" along and introduce him to other guests.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsFootball Review

December 1938 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

December 1938 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

December 1938 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Article

ArticleProposed Mew Webster Hall

December 1938 -

Article

ArticlePublications Decision by Trustees

December 1938 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912*

December 1938 By CONRAD E. SNOW