by George Hill Evans '99; Publication No. 1 of the Conway, N. H., Historical Society; 1939. 135 Pages.

This is a delightfully written and well documented story of the upper valley of the Saco River, in the section now occupied by the towns of Fryeburg, Maine, and Conway and Bartlett in New Hampshire. The word Pigwacket, with its many varities of spelling, belonged originally to a tribe of the Abnaki (Abenaqui, Wobanaki) Indians who inhabited these fertile uplands and Intervals,—that being a preference of spelling over Intervale, since the former means between walls and the latter between valleys. The WTiter goes into the history of this region, at once one of the most pleasant in New England both in Love well's day and this, and with sympathetic touch describes the incoming of white warriors and settlers and the defence of the region by the tribe that lived there.

In this book, which is, presumably to be followed by others, the story comes to an end with Lovewell's famous fight in though in an "Aftermath" the summary of succeeding events, clear to the St. Francis Massacre by Robert Rogers in 1759, tells of the fate of the fugitives from pigwacket at St. Francis and their final incorporation with the British government.

It is really curious how little most people know about this district which is so full of history. All about it, even today exists one of the wildest regions in the whole of New England. On the West is the mountain wall of Moat and Chocorua, on the south a range of peaks 1,400 to 1,500 feet high, on the east "a confusion of lakes, bold highlands, and the wall of Pleasant Mountain," with also the Saco valley extending down toward the sea. On the north the valley "separates into groping tentacles, reaching into the mountain defiles of Bartlett, Jackson, and Chatham," and on the skyline to the northwest is "Kodaakwajo, the Abnaki's Hidden One, our Mt. Washington." Truly one of the most magnificent wildernesses that the white race ever pushed into.

Here was staged the long siege that gave the Colonists possession finally of this land. Mr. Evans describes the approaching trails, —there were two main approaches described as the jaws of a nutcracker,—one by the lakes, chiefly Ossipee, and the other directly by the Saco Valley. Eventually the storming forces crushed resistance by pressure from both sides. After that there was nothing for the Indians to do but to retreat to their final home in Odanak at St. Francis, resigning them- selves with sadness to the loss of these fertile fields as well as of the meadows farther north at the Coos meadows (New- bury, Vermont) and to merge their tribe with the others that had taken refuge in the Canadian village.

But the book is not only history,—it is written simply, in a style that gives it verisimilitude, like the Indian captives' stories of old, or that History of the CoosCountry by Grant Powers. Before beginning the book, the writer must have been well versed in the elements of the Abenaki language,—indeed he pays tribute to one Odanak writer,—Sozap Lolo, a chief at St. Francis, who, like a predecessor, Henry Masta, now living in retirement, wrote a grammar of his language for the perpetuation of a language that seemed doomed. The settlement at Odanak has long had a connection with Dartmouth College and has sent many students to the college or Moor's School since 1770. Besides many Indian notes the writer has appended a list of 68 variants in the spelling of Pigwacket itself.

But as simplicity moves swiftly into romance, so the actual recorded events of the book move quickly into enthralling tales of wilderness adventure, of "captivated" prisoners, of exploration, of battle, of ambush, of long flights, of winter travels and well nigh incredible happenings. The truth, in well-written narrative and a theme in easily comprehensible development, will give much delight to those who ride the Ossipee trail, or glide down the Crawford Notch road or spend the summer somewhere in this happy Pigwacket Basin. The references listed at the end will furnish more reading, and there in the appended portion will be found some of the Love- well Fight Ballads so popular in New England long ago, and also that Longfellow poem which appeared when the boy was but 13.

Pigwacket,—Pagwaki, Paquakig, Paqukig, Pauquaukit,—clear down to No. 68 which is Piqwacket.

E. P. Kelly '06.

Books

-

Books

BooksA DARTMOUTH POET

JUNE 1932 -

Books

BooksART AS AN INVESTMENT.

January 1962 By CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Books

BooksSABOTAGE! THE SECRET WAR AGAINST

November 1942 By Herbert f. West '22. -

Books

BooksDIPLOMATS IN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION.

FEBRUARY 1963 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

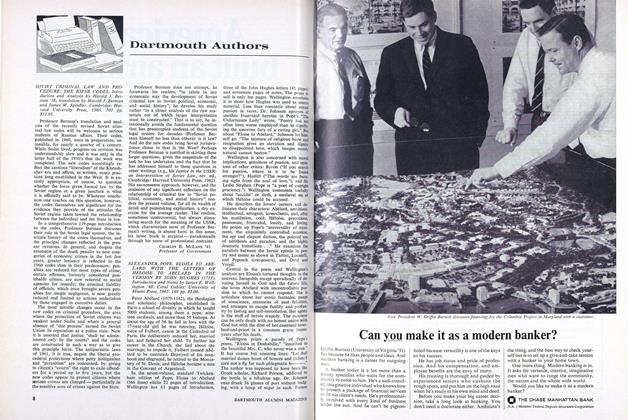

BooksALEXANDER POPE. ELOISA TO ABELARD WITH THE LETTERS OF HELOISE TO ABELARD IN THE VERSION

MAY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksDAS DEUTSSCHE DRAMA IM AMERI KANISCHEN COLLEGE-U. UNIVERSITAETS—THEATER

May 1938 By Royal C. Nemiah