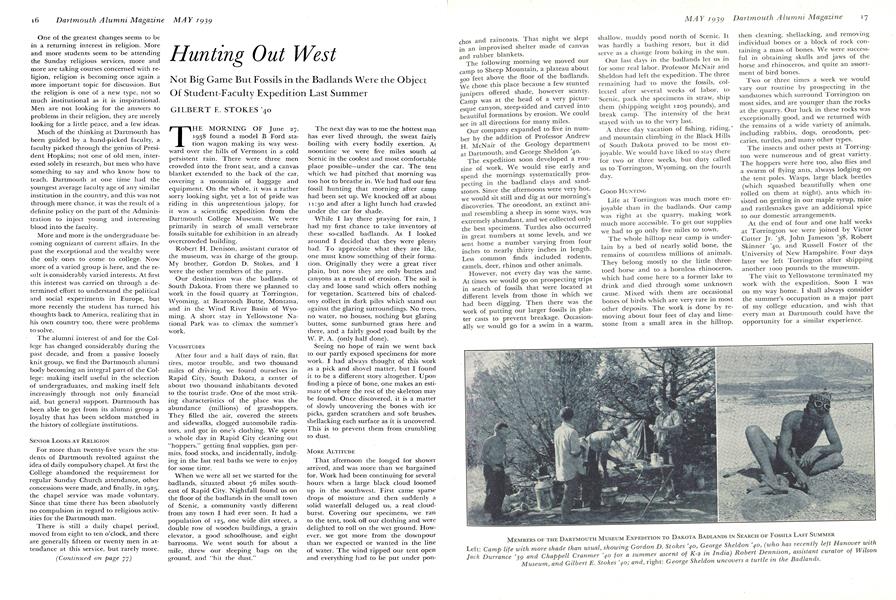

Not Big Game But Fossils in the Badlands Were the Object Of Student-Faculty Expedition Last Summer

THE MORNING OF June 27, 1938 found a model B Ford station wagon making its way westward over the hills of Vermont in a cold persistent rain. There were three men crowded into the front seat, and a canvas blanket extended to the back of the car, covering a mountain of baggage and equipment. On the whole, it was a rather sorry looking sight, yet a lot of pride was riding in this unpretentious jalopy, for it was a scientific expedition from the Dartmouth College Museum. We were primarily in search of small vertebrate fossils suitable for exhibition in an already overcrowded building.

Robert H. Denison, assistant curator of the museum, was in charge of the group. My brother, Gordon D. Stokes, and I were the other members of the party.

Our destination was the badlands of South Dakota. From there we planned to work in the fossil quarry at Torrington, Wyoming, at Beartooth Butte, Montana, and in the Wind River Basin of Wyoming. A short stay in Yellowstone National Park was to climax the summer's work.

VICISSITUDES

After four and a half days of rain, fiat tires, motor trouble, and two thousand miles of driving, we found ourselves in Rapid City, South Dakota, a center of about two thousand inhabitants devoted to the tourist trade. One of the most striking characteristics of the place was the abundance (millions) of grasshoppers. They filled the air, covered the streets and sidewalks, clogged automobile radiators, and got in one's clothing. We spent a whole day in Rapid City cleaning out "hoppers," getting final supplies, gun permits, food stocks, and incidentally, indulging in the last real baths we were to enjoy for some time.

When we were all set we started for the badlands, situated about 76 miles southeast of Rapid City. Nightfall found us on the floor of the badlands in the small town of Scenic, a community vastly different from any town I had ever seen. It had a population of 125, one wide dirt street, a double row of wooden buildings, a grain elevator, a good schoolhouse, and eight barrooms. We went south for about a mile, threw our sleeping bags on the ground, and "hit the dust." The next day was to me the hottest man has ever lived through, the sweat fairly boiling with every bodily exertion. At noontime we were five miles south of Scenic in the coolest and most comfortable place possible—under the car. The tent which we had pitched that morning was too hot to breathe in. We had had our first fossil hunting that morning after camp had been set up. We knocked off at about 11:30 and after a light lunch had crawled under the car for shade.

While I lay there praying for rain, I had my first chance to take inventory of these so-called badlands. As I looked around I decided that they were plenty bad. To appreciate what they are like, one must know something of their formation. Originally they were a great river plain, but now they are only buttes and canyons as a result of erosion. The soil is clay and loose sand which offers nothing for vegetation. Scattered bits of chalcedony collect in dark piles which stand out against the glaring surroundings. No trees, no water, no houses, nothing but glaring buttes, some sunburned grass here and there, and a fairly good road built by the W. P. A. (only half done).

Seeing no hope of rain we went back to our partly exposed specimens for more work. I had always thought of this work as a pick and shovel matter, but I found it to be a different story altogether. Upon finding a piece of bone, one makes an estimate of where the rest of the skeleton may be found. Once discovered, it is a matter of slowly uncovering the bones with ice picks, garden scratchers and soft brushes, shellacking each surface as it is uncovered. This is to prevent them from crumbling to dust.

MORE ALTITUDE

That afternoon the longed for shower arrived, and was more than we bargained for. Work had been continuing for several hours when a large black cloud loomed up in the southwest. First came sparse drops of moisture and then suddenly a solid waterfall deluged us, a real cloudburst. Covering our specimens, we ran to the tent, took off our clothing and were delighted to roll on the wet ground. However, we got more from the downpour than we expected or wanted in the line of water. The wind ripped our tent open and everything had to be put under ponchos and raincoats. That night we slept in an improvised shelter made of canvas and rubber blankets.

The following morning we moved our camp to Sheep Mountain, a plateau about 300 feet above the floor of the badlands. We chose this place because a few stunted junipers offered shade, however scanty. Camp was at the head of a very picturesque canyon, steep-sided and carved into beautiful formations by erosion. We could see in all directions for many miles.

Our company expanded to five in number by the addition of Professor Andrew H. McNair of the Geology department at Dartmouth, and George Sheldon '40.

The expedition soon developed a routine o£ work. We would rise early and spend the mornings systematically prospecting in the badland clays and sandstones. Since the afternoons were very hot, we would sit still and dig at our morning's discoveries. The oreodont, an extinct animal resembling a sheep in some ways, was extremely abundant, and we collected only the best specimens. Turtles also occurred in great numbers at some levels, and we sent home a number varying from four inches to nearly thirty inches in length. Less common finds included rodents, camels, deer, rhinos and other animals.

However, not every day was the same. At times we would go on prospecting trips in search of fossils that were located at different levels from those in which we had been digging. Then there was the work of putting our larger fossils in plaster casts to prevent breakage. Occasionally we would go for a swim in a warm, shallow, muddy pond north of Scenic. It was hardly a bathing resort, but it did serve as a change from baking in the sun.

Our last days in the badlands let us in for some real labor. Professor McNair and Sheldon had left the expedition. The three remaining had to move the fossils, collected after several weeks of labor, to Scenic, pack the specimens in straw, ship them (shipping weight 1203 pounds), and break camp. The intensity of the heat stayed with us to the very last.

A three day vacation of fishing, riding, and mountain climbing in the Black Hills of South Dakota proved to be most enjoyable. We would have liked to stay there for two or three weeks, but duty called us to Torrington, Wyoming, on the fourth day.

GOOD HUNTING

Life at Torrington was much more enjoyable than in the badlands. Our camp was right at the quarry, making work much more accessible. To get our supplies we had to go only five miles to town.

The whole hilltop near camp is underlain by a bed of nearly solid bone, the remains of countless millions of animals. They belong mostly to the little threetoed horse and to a hornless rhinoceros, which had come here to a former lake to drink and died through some unknown cause. Mixed with them are occasional bones of birds which are very rare in most other deposits. The work is done by removing about four feet of clay and limestone from a small area in the hilltop, then cleaning, shellacking, and removing individual bones or a block of rock containing a mass of bones. We were successful in obtaining skulls and jaws of the horse and rhinoceros, and quite an assortment of bird bones.

Two or three times a week we would vary our routine by prospecting in the sandstones which surround Torrington on most sides, and are younger than the rocks at the quarry. Our luck in these rocks was exceptionally good, and we returned with the remains of a wide variety of animals, including rabbits, dogs, oreodonts, peccaries, turtles, and many other types.

The insects and other pests at Torrington were numerous and of great variety. The hoppers were here too, also flies and a swarm of flying ants, always lodging on the tent poles. Wasps, large black beetles (which squashed beautifully when one rolled on them at night), ants which insisted on getting in our maple syrup, mice and rattlesnakes gave an additional spice to our domestic arrangements.

At the end of four and one half weeks at Torrington we were joined by Victor Cutter Jr. '38, John Jameson '38, Robert Skinner '40, and Russell Foster of the University of New Hampshire. Four days later we left Torrington after shipping another 1000 pounds to the museum.

The visit to Yellowstone terminated my work with the expedition. Soon I was on my way home. I shall always consider the summer's occupation as a major part of my college education, and wish that every man at Dartmouth could have the opportunity for a similar experience.

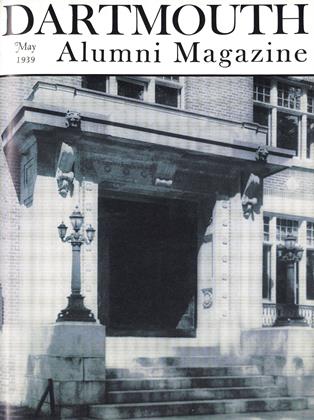

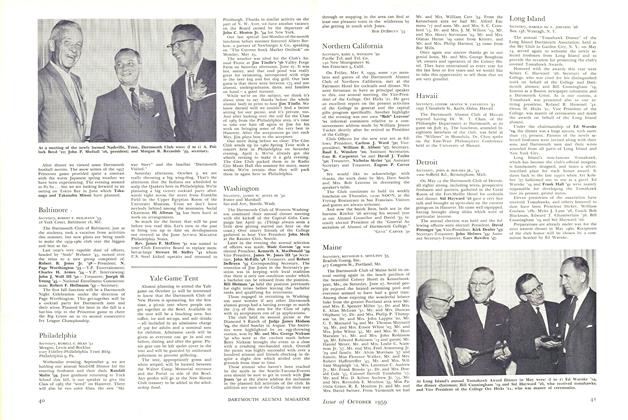

MEMBERS OF THE DARTMOUTH MUSEUM EXPEDITION TO DAKOTA BADLANDS IN SEARCH OF FOSSILS LAST SUMMER Museum, and Gilbert E. Stokes '40; and, right: George Sheldon uncovers a turtle in the Badlands.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1939 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

Article"Where, Oh Where—?"

May 1939 By Jonh Parke '39 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1939 By RALPH N. HILL JR. '39 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Poet Laureate

May 1939 -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

May 1939 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

May 1939

Article

-

Article

ArticleFOUR WEBSTER AVENUE LOTS OPENED TO FRATERNITIES

March, 1924 -

Article

ArticleYale Game Tent

October 1959 -

Article

ArticleThe Fund

SEPTEMBER 1981 -

Article

ArticleThe Final Standings

SEPTEMBER 1998 -

Article

ArticleArt in the Round

NOVEMBER 1998 By Alex Arcone -

Article

Article"THE COLLEGE ON THE HILL"

June 1935 By W. J. Minsch Jr. '36