DRAMATIC ORGANIZATION PICTURED AS A VITAL, PATTERNED GROUP

YOU'RE UNINFORMED if you think the Players aren't a patterned group, and you're malicious if you think they're stereotyped. That leaves a middle course that ought to be just about right in summing them up.

The Players are a dramatic organization. They concern themselves, with amazing success, with the art of producing plays, and in so doing they necessarily contract a little more than a touch of that self-consciousness that seems to hit all art groups in greater or lesser degree.

Their self-consciousness, far from being either binding or obnoxious, is sometimes witty and sometimes not so witty, and usually manifests itself in constant shop-talk and, more significantly, in everlasting mimicry. That word "everlasting" isn't intended to connote disgust—it is intended to mean what it says-that the Players find no end of pleasure in imitating to themselves everything from Groucho Marx to the sound of running water.

ADEPT AT IMITATING SELVES

In fact, they are particularly adept at imitating themselves. They enjoy one another, they find one another pretty funny, and they say so—with dramatic sufficiency. They have rather less of an arty touch than one might suppose, and certainly make none of those ungodly claims to intellectualism that could so easily find a home in that sort of environment.

Some of them eat together in the new dining hall, and there Playeromania is rampant at its best and its worst. There they laugh loudly at their own particular brand of humor (usually, again, in the form of mimicry); there they draw pictures of stage-sets on the menu-cards; there they quietly orate to one another concerning Benjamin Franklin, The Dartmouth, Raymond Massey, or mud-puddles; and there they display their idiosyncrasies (e.g.— talking through one's nose and wagging one's entire face when one describes almost anything), but those either die out or are made funny, so that everything is fine in the end.

One thing that the Players do with remarkable consistency is put out good shows —and they work hard to do it. Largely responsible for the organizing and coordinating of that work are the three non-undergraduate executives, Warner Bentley, Henry Williams, and Ted Packard, whose problem it is to adapt their ideas and their capacities to college limitations and to temper their personalities to student life.

Warner Bentley, officially known as the director, exercises what is pretty much of a benevolent dictatorship in his own particular field—directing the shows. Henry Williams, when he is not either entertaining or advising the boys, is making things. Henry is constantly making things; he makes anything out of anything and it always looks just right for the purpose. Officially, he is technical director—which means director of crews, supervisor of set-designing and execution, costume designer, and a whole row of at ceteras. Ted Packard, largely concerned with the Experimental Theater, has broadened the scope and intensified and bettered the work of that growing department. But besides that he shuffles in and out of the regular Players work, making himself valuable as an assistant to Warner Bentley.

This doesn't mean that the students don't work. As a matter of fact, they are the Players, and the efficiency of the non-undergraduate executives doesn't change that fact in the least. If the undergraduate members weren't so completely synonomous with the organization to which they belong, they wouldn't develop the typically "Players personality" that vaguely colors their individual personalities. The very fact that there is something of a character pattern to the organization attests its vitality and its hold on its members.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1939 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

Article"Where, Oh Where—?"

May 1939 By Jonh Parke '39 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1939 By RALPH N. HILL JR. '39 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Poet Laureate

May 1939 -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

May 1939 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

May 1939

John D. Hess '39

Article

-

Article

ArticleMEETING OF SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

February 1916 -

Article

ArticleFRESHMEN SUCCEED IN TAKING CLASS PICTURE

June, 1923 -

Article

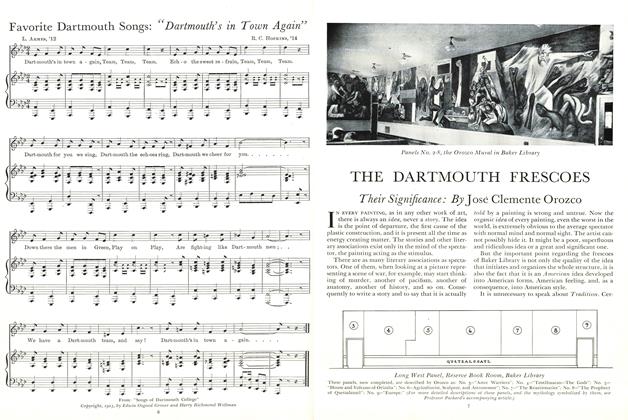

ArticleFavorite Dartmouth Songs: "Dartmouth's in Town Again"

November 1933 -

Article

ArticleWar Activities Filmed

August 1942 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE ANSWERS

December, 1923 By HARRY R. WELLMAN -

Article

ArticleCAMPUS MOURNS TUCK DEATH

June 1938 By Ralph N. Hill '39