Parallels Between World War I and Present Emergency Provide Base For Defense Plans of the College

EVERY ONE OF us is BY NATURE, IN Horace's phrase, a laudator temporisacti: "things are not what they used to be." We are prone to compare unfavorably the America and the Dartmouth of today with the America and the College which watched the approach of the first World War. But, as a matter of fact, the similarities, the parallels of thought and action are more striking than the dissimilarities, the divergencies.

If we feel impatient with America's lag in comprehending the realities of the current world situation, we can check our hasty judgment by reviewing experiences of a quarter of a century ago. One such experience, centering around a Kaiser Wil- helm exchange professor and occurring shortly before the outbreak of the first World War, remains vividly in the mind of the writer. The professor was addressing the Phi Beta Kappa Alumni Association of New York City and vicinity—as cosmopolitan a gathering as America could assemble. The speaker discussed European politics, while his audience sat aghast. Here was power politics pure and undefiled, with no concealment of the assumption that the final arbitrament was war.

No sooner had the distinguished guest sat down than many voices of protest were heard from the floor: "The thought in the mind of the world was of peace, not of war, and violence on the scale assumed by the speaker was a bararism beneath the enlightenment of our times." The German savant was as amazed at the attitude of his hosts as they were at his. Within a year the World War engulfed civilization. Yet America still refused to believe in the existence of power politics; still insisted on living in a world of unreality.

The colleges showed no greater comprehension. For, after all, the college world is only a small scale replica of the larger world. As America was slow, at that time, so were the colleges slow, to perceive the trend of world events. It might be a good penitential exercise for critics of the undergraduate of the present day to leaf over the issues of The Dartmouth for the years leading up to our entrance into the first World War. Here is the record as it appeared in the undergraduate newspaper.

When the College convened in the fall of 1914, President Nichols, in the convocation address, stated as his view of America's role: "Thank God, our nation, from her position, can, through wisdom, guarded speech and act, and righteousness toward all, escape ill-will and chance of future bloodshed." And though Professor F. M. Anderson explained the "real causes of the war, emphasizing particularly the military method of the establishment of German unification,"—so reads the summary—the Deutscher Verein, on opening its permanent headquarters in Robinson Hall, stated: "It will be the aim of the Club, this year, to consider the European war from the German point of view." The editorials, oblivious of the outside world, pontificated on fraternities, football, the food in Commons, or on Dartmouth Night.

The first casualty among the faculty, the death of Professor Klippfell who fell in October, fighting for France, brought strictly neutral regrets; and, in January, a news item of an anti-militarism meeting at Columbia University elicited the traditional editorial comment on Dartmouth's geographical remoteness. Thus the academic year 1914-15 passed, from the official student standpoint, at least, with no taking of sides, with no apparent attention to Dogger Bank, poison gas, the Gulflight, the Lusitania, or the other events of that titanic conflict.

"DISTURBING THE PEACE"

The next year, 1915-16, shows little change in campus attitudes. In his opening greeting President Nichols is able to declare: "That we are still at peace with all men is a blessing beyond measure. There are times of stress when it takes more courage not to fight than to go to war." The editor-in-chief of the year, Roswell Foster Magill, nailed to his masthead the words of the young Ruskin: "I have a great hope of disturbing the public peace in many directions"; and, although that dire threat seems unfulfilled, he compensated with editorials which were models of undergraduate maturity for any time, to say nothing of a period when the Lebanon Lyric advertised Fritzi Scheff in "Pretty Miss Smith" and The Inn featured "Electric Lights and Baths" as outstanding modernities.

However, a greater awareness of the outside world is evident during the consulship of Magill. The International Polity Club announced a series of discussions on preparedness, seemingly strongly anti. Lord Dartmouth's letter to Doctor Tucker on the death of his second son at the Dardenelles "I am glad to think that the sons of Dartmouth have given all they can"—was received with genuine sympathy by the undergraduate editor though without be- traying any partisan bias in favor of the Allies. By the first of November the editor, commenting on what had been accomplished at Yale, Princeton, Williams, and elsewhere in the adoption of military training, asserts: "Dartmouth undergraduates certainly should not be the last to express an opinion as a body, either for or against armament or military drill in some form. It is time that Dartmouth took some definite step in the matter." This editorial in favor of preparedness brought forth angry Vox Pops, and evidently there was a schism in the Dartmouth board; for one of the members actually resorted to the letter column to express his opposition: "It is a harmful contribution to that ever-increasing mass of articles which is inflaming the American public with a desire for militaristic action."

MILITARY DRILL ON CAMPUS

Nevertheless the editor stuck to his guns and, while some undergraduates, denied any official status by Palaeopitus, sailed in the Ford Peace Ship, other students, aided financially by Johnny John- son '66, and supported by the personal en- thusiasm of Dean Laycock, Professors Emery, Goldthwait, Fletcher, and others, went about the job of arousing interest in military drill. However, the initiative seemed to come largely from the students and their Preparedness Committee. Presi- dent Nichols, announcing that the faculty would take up the problem definitely, dis- counted the current argument that military training would make men warlike, but declared that the faculty should be neutral and take the attitude: "If enough of the students want it, let them have it."

The activities of Dartmouth ambulance drivers, the tragic- death of Dick Hall '15, and support of the preparedness movement by prominent alumni brought about the formation of a voluntary battalion of 130 men, and drill was finally begun in the Alumni Gymnasium, on February 7, 1916, "in tennis shoes, without arms or uniforms." This made no part of the curriculum and the battalion was the object of a good many jeers, if the editorial column can be believed.

The Trustees at the February meeting, 1916, appointed a committee consisting of Doctor J. M. Gile, Mr. F. S. Streeter, and Mr. L. Parkhurst to consider the question of military training in the College. Shortly thereafter, the voluntary battalion received arms and uniforms. Interest fluctuated during the spring of 1916. In March, The Independence League was formed for the ostensible purpose of opposing the introduction of military training into the curriculum, and, conducting a poll, showed that 470 students were opposed to, 303 in favor of, the inclusion of military instruction among the college courses. And Vox Pop pacifistically fulminated against the singing in Chapel of militant hymns, "The Sons of God Go Forth to War" and "On- ward Christian Soldiers," as arousing a spirit of war passion!

One encounters in news report, editorial comment, and letter column much intense feeling and violent debate, finding expression in such phrases as, "Hermaphrodites" (though there is a question here as to whether the editor really knew the meaning of the word), "our hyphenated pacifist," "Ananias Clubs," "members of that school of pacifism of which Mr. Bryan is the bright particular example," etc.

In March 1916, a committee composed of Professor E. J. Bartlett, Dean Laycock, Professor C. D. Adams, and others urged, on behalf of the faculty, that students take the Plattsburg training and groups of men did enlist for the camps and navy cruises of that summer. Dartmouth alumni offered to pay the expenses of those who otherwise could not afford to go. This trend was aided by Wilson's demand on Germany to abandon its methods of submarine war- fare, though the same issue of The Dartmouth in which this appeared carried a passionate protest against the exhibition of Canadian war posters in the Library: "These highly inflammatory posters might well, by their appeal to the emotions, lead a student into an unsound and ill-considered stand on the question of national preparedness."

On April 17, 1916, Messrs. Streeter, Nichols, Laycock, Anderson, Fletcher, Foster, and G. D. Lord signed a petition in support of the Entente Allies, which indicates something short of entire neutrality in certain quarters. About the middle of May an incident occurred which must have been quite a cause celebre. The editor of Jack-O'Lantern was separated from college for an editorial directed against the faculty vote which granted academic credit for attendance at Plattsburg. A thousand undergraduates petitioned against this faculty discipline, the cry of freedom of speech was raised, and the complaint was heard that the members of the faculty, being war lords (sc. war mongers), "executed" the only undergraduate who dared oppose their policy. The explanation offered, that personal abuse, and not freedom of speech, was the matter involved, satisfied the undergraduate editor, who was on the preparedness side.

The academic year 1916-17 saw the inauguration of President Hopkins, looking very young in the high white choker of that day, and the annual change in the directorate of The Dartmouth. Football; the Hughes-Wilson campaign; an evangelistic invasion by Billy Sunday ("No single event in the history of the present college generation has aroused more vital interest throughout the college community"); the Nugget (Bill Cunningham '19, Manager), advertising admission at ten cents', protests against the denial of the local franchise to students—of such was the farrago of student editorial interest during this critical year. Of course, the personnel of the Dartmouth directorate may have been less international-minded, and this may well account for the silence; but there seems a lessening of undergraduate tension and of attention to matters of war and preparedness until February of 1917.

Then the tempo accelerated. On February 17, President Hopkins appointed a special committee of faculty and undergraduates "to take up immediate plans for what Dartmouth should do, if anything, in the line of preparedness in order that we may be ready for whatever may result from the international crisis." A questionnaire of March 8, 1917, showed an undergraduate vote of two to one that we were justified in declaring war "in view of the existing international situation," but four to one against making any such declaration; and if war were declared only one out of three answered that he would probably volunteer. This would not strike us, today, as particularly impressive. But the editors, who had pointed with reproach to Dartmouth's lagging, compared with progress in preparedness at other colleges, declared that the results of this vote, which they found highly gratifying, had been arrived at "without a single flag-waving militarist having visited Hanover during the present college year."

According to The Dartmouth of March 17, 1917, the faculty voted unanimously to introduce a course in military training into the curriculum, but the students responded so slowly to this move that the editorial of March 24th made "Pitiful Comparisons": "at Princeton 900 undergraduates enlisted in the course in military training, over 1200 at Harvard" and continued: "It is indeed fortunate that Easter vacation will raise so soon the mask of misguided pacifism that has sowed the seeds of disloyalty in men who would be insulted if told they were not giving wholehearted support to America." George W. Wickersham arrived two days later on a swing around the country to arouse interest in military training and when the boys returned to Hanover war had been declared.

How promptly, efficiently, and completely the College thereupon devoted itself to national service is a matter of well-known record and need not be recapitulated.

This chronological summary of undergraduate reaction to approaching war has more than a curious or sentimental interest. It is one of the few measuring rods by which we can compare the two war-time generations of Dartmouth students. The neurotic note and the note of self-pity are not in evidence. But there are in evidence abundant apathy, a tardy realization of what was happening in the world, and a large and articulate group opposed to preparedness. And let us not forget that, less than one month before the declaration of war, approximately eighty per cent of the students voted against making such a declaration. The golden haze over the past should not obscure these realities which we are prone to forget.

DARTMOUTH DOING DUTY The sequel inspires confidence for the present hour. On June 18, 1917, The Dartmouth could honestly say: "True to tradition, Dartmouth has responded as a unit to the Country's call. Every last man is doing his bit; the shirker is an unknown quantity. Dartmouth's spirit is being made manifest as the truest form of red-blooded patriotism. Boys of eighteen carried the burdens of the Civil War-on the college man of today falls no insignificant part in the conduct of the war. Dartmouth did its duty in 1861. It is doing it today."

If a comparison is made of the record in The Dartmouth of 1939-41 with the above summary, there will be found no deterioration, intellectual or moral, in the student body, but rather a heightened seriousness and a sounder understanding. The factor of President Hopkins' influence over undergraduate thinking in this latter period is difficult to define precisely, but impossible to exaggerate. To be sure the editorial policy remained isolationist through March of 1940 under Tom Braden, one of the paper's great editors, and sponsored the sentiments of that camp. But on October 30, 1940, the succeeding board, under the leadership of Bob Harvey and Charles Bolt 6, after a half year of vacillation, came out for aid to Britain and conscription.

Nor was that all. When the editorial mantle fell upon the shoulders of Jerry Tallmer in the hour of Greece's tragedy, he printed on the front page of The Dartmouth a brilliant letter.by Bolte addressed to President Roosevelt, urging war upon Germany. The letter, with the reiterated "Now we have waited long enough," became famous. It was reprinted by newspapers throughout the country and finally made its way into the Congressional Record, there to sleep an uneasy eternity, a strange bedfellow of the brain children of Tobey and Nye. Tallmer accepted Bolte's credo for The Dartmouth and there the matter rests. What most impresses us in the present picture are the superior awareness of the undergraduate of today, his utter lack of indifference to world events, and his consciousness of a personal responsibility in making his decision. He does not suffer a whit in comparison with the student of a generation ago.

Colleges are notoriously slow in comprehending the approach of war. War is a debased activity, outmoded and barbarous, eliminated from school histories, with no more standing in academic halls than a prohibitionist in a Frenchman's wine cellar. To the writer, returning to Hanover from Italy in September 1939, the realization of what the outbreak of war meant to America and to the world seemed neither profound nor wide-spread. But by the turn of the year so many individuals in the Dartmouth community had discovered means of participating in the program of national defense that President Hopkins, in September of 1940, appointed a committee to coordinate and expand these activities, which adopted the name of American Defense Dartmouth Group.

Professor H. J. Tobin was appointed chairman of the Central Committee of the Group. As a steering committee its task was to coordinate the defense work which was being carried on by special subcommittees. This Central Committee, at an early meeting, defined its attitude toward the world conflict in a unanimous vote which declared "that the United States should take whatever action is necessary to prevent the Axis powers from winning the war." This ideology, however, was not binding upon the subcommittees and they were free to act independently of the Central Committee's stand. President Hopkins emphasized the freedom which he desired for the Group in a letter to the chairman in which he wrote: "I have endeavored to indicate that it (the Dartmouth Group) should operate quite apart from the Administration or from the Board of Trustees."

Notes 011 the activities o£ this Dartmouth Group have appeared in THEDARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE monthly. The subcommittees have performed numerous functions during the past year. The Committee on Military Service registered the students under the Selective Service act; it accumulated information on military service, made it available to students, alumni, faculty, and members of the community; it held regular office hours and answered the countless questions of students concerning the filling out of questionnaires, opportunities in the various armed services, and grounds for deferment.

The Committee on Civilian Opportunities for Defense analyzed information in this complicated field and on the basis of its studies was able to provide guidance for alumni and for students in connection with defense industries.

The Committee on Press and Writing organized the faculty to perform the duty of enlightening public opinion through the publication of special articles and open letters on defense problems and American foreign policy. In addition a letter writing group of forty-odd members of the faculty contributed letters to the press on the basis of topics suggested from time to time by the committee. These publications have appeared in large numbers of newspapers from coast to coast and must have caught the eye of Dartmouth alumni everywhere.

The Committee on Public Speaking and Radio has performed a similar function with the spoken word, offering to some four hundred civic organizations in New Hampshire and Vermont the services of a large number of the faculty specially qualified to speak on problems of national defense. The response was immediate and heavier demands are being made on the committee from month to month.

The Committee on War Aims and Peace Plans has systematically explored the literature bearing on these topics, and lists of recommended readings have been published through THE DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE and elsewhere. The Committee on Appeals and Drives undertakes to investigate and report on any organization which solicits funds or engages in relief activities in the town of Hanover or in the surrounding regions. The Committee on Refugee Children performed the function indicated by its title until the British abandoned the plan of sending children abroad. Since then it has cooperated with various organizations devoted to philanthropic services in behalf of European children. The Committee on Civil Liberties, the formation of which was prompted by the experience of the United States during the first World War, has met no call upon its services up to the present and its activities have been limited to the accumulation of information.

This Dartmouth Defense Group, with its special subcommittees mentioned above, is functioning effectively, collaborating with the New Hampshire State Council of Defense and with all the local and regional groups, and maintains contacts with defense groups throughout the country. The subcommittees are continuing the activities indicated.

However, as previously stated, the Defense Group was, in President Hopkins' words, to "operate quite apart from the Administration or from the Board of Trustees." It could only make suggestions or recommendations to the faculty. And the feeling had been growing that a formal committee within the organization of the College and under the direction of the President was needed, which should be em- powered to act promptly in all matters con- cerning the curriculum in its relation to national defense. In answer to this demand, the Trustees, at a meeting on April 20, 1941, established the Committee on Defense Instruction, by a unanimous vote, which reads, in part, as follows:

"That a Committee on Defense Instruction be established under the direction of the President to study the problem of relating the curriculum of the College and of the Associated Schools to the emergency of national defense and that authority be conferred upon the Committee to take such action in behalf of the Trustees as may be necessary to make effective such conclusions as may be reached. ....The Committee will determine both in the immediate or the more long range view in what ways, within the curricular structure of the liberal arts college and in keeping with its traditional purposes, Dartmouth can best fit its students for service in this period of national crisis The Committee will be appointed by the President and he will be chairman of it The Committee will report through the President to the Board of Trustees."

It will be seen from this vote that the Trustees intended that the Committee on Defense Instruction should have ample emergency power to act with great speed in the crisis and cut red tape with the President as chairman, liaison between administration and faculty is constant and immediate. Its jurisdiction is not confined to the College; it extends to the Associated Schools as well. Though the Committee is not expected, (nor would it be wise), to turn the curriculum upside down in one of those cyclic convulsions which all colleges experience in normal times from their committees on educational policy, it has a liberal range of action in curricular matters, as is shown by the vote of the Trustees quoted above.

The Committee, as finally staffed, consists of three administration and seven faculty members: a broad enough base to be representative of the different points of view in the college as a whole. The membership and representation are as follows:

President Hopkins, Chairman; Wm. Stuart Messer, Vice Chairman, Division of the Humanities: E. Gordon Bill, Dean of the Faculty; Andrew J. Scarlett, Chairman of the Committee on Educational Policy; Anton A. Raven, Division of the Humanities; Harold M. Bannerman, Division of the Sciences; Bancroft H. Brown, Division of the Sciences; Earl R. Sikes, Division of the Social Sciences; Andrew G. Truxal, Division of the Social Sciences; Sidney C. Hayward, Secretary of the College.

This Committee held its first meeting on April 27, 1941, with President Hopkins in the chair, home over the week-end from his OPM duties in Washington, and it has met frequently since with either the President or the Vice Chairman presiding. There were difficult problems to be solved. It wished to avoid the mistakes of 1917-18. Those of us who had taken part in the direction of the Students' Army Training Corps had no desire to see resurrected that unhappy experiment, which gave no promise of producing either students or soldiers. Nor did the Committee wish to follow the example of that college which, in the present emergency, had naively wired to President Roosevelt and to various departmental heads in Washington that its plant and personnel were entirely at their disposal! At the same time the Committee was determined that the College should make the utmost contribution to national defense.

Of course Dartmouth would never attempt to emulate the technical school; it must cherish a long-term as well as a shortterm view of the nation's needs. In its first communication to the undergraduate body the Committee made clear this double duty where it urged "that each student should explore the possibility of combining with his major interest at Dartmouth— which must be primarily a liberal education some training in elective hours which would qualify him for maximum usefulness in the present emergency."

President Hopkins, in a letter under date of July la, 1941, addressed "To Dartmouth Students and Parents," has outlined some of the tasks so far accomplished by the Committee and has stated what may be accepted as the attitude of the College in facing this crisis. The letter reads in part as follows:

"Dartmouth, through its long history, has been primarily a liberal arts college, seeking to give a man broad cultural background for later professional studies and for active participation in business life. As we see it, that is still our primary task, in war as well as in peace; to help young men to be better informed, more intelligent citizens (and, as needed, citizen-soldiers); to aid them to lead in after years fuller and richer and more useful lives.

"In adapting our curriculum to the present emergency, the College, too, has been mindful of the need to balance long-run and shortrun objectives. We have introduced several short courses immediately helpful to men facing military service. We have altered the emphasis of others where it will make them more directly valuable under present conditions. Some of the new courses are designed to give students a better understanding of world problems, their causes and the efforts proposed for their solution, in accordance with the underlying purpose of the College. The liberal arts college now has a clear duty to do all it can to aid in national defense; at the same time it would be derelict in its most important obligation if it lost sight of the purposes for which it primarily exists and the coming generation's need for college-trained men."

There need be no fear that Dartmouth will sell or despise its birthright.

From the standpoint of morale the College must convince the student that it is still within his power to do two things: first, to follow out and specialize along the line which he has always wished to pursue, however remote it may seem from tanks or dive bombers; and, secondly, in his elective hours, to equip himself with some special skills which are in. demand in this machine age for immediate service with the colors and in defense industries. As soon as this conviction takes firm root in the undergraduate mind, the individual will work more cheerfully at his long-range aim, and will be comforted by the assurance that if his country suddenly demands his help he can render full measure of service through having employed wisely his elective hours.

No responsible authority, Washington least of all, wishes to disrupt the work of the liberal college. President Roosevelt, Paul V. McNutt, recently a university dean, J. W. Studebaker, U. S. Commis- sioner of Education, have all emphasized this point of view. As late as July 30, 1941, Colonel W. A. Burress, representing the training division of the Army, stated in a conference of college and university presidents held in Washington: "The War De- partment has felt and still feels that a good schooling of mind and body is a positive source of strength in any event; that the college world in carrying out its normal role, is making a most important and necessary contribution to National Defense. It, therefore, favors the continued operation of educational institutions, as such, with as little disruption as possible, and it has not in any way desired to advocate or sponsor a reorientation of college courses."

LIBERAL ARTS PREPARATION

The explanation of this point of view is obvious. An all-out war is as diverse as the life of a nation: it demands as many skills as the arts of peace. A study of the releases emanating from Washington, which describe the training requisite for national service in this time of crisis, demonstrates strikingly how the liberal arts college prepares its undergraduates for emergency needs. Some of the armed forces demand as prerequisite the completion of the entire work for a college degree, others half so much, with little reference to specific requirements as to subject matter. Likewise the Civil Service Commission has established the Junior Professional Assistant examination "to recruit young college graduates for junior professional and scientific positions in the Federal Government," and more than fifty per cent of the categories are satisfied by the usual Major requirements in Dartmouth College. The basic courses of the curriculum, therefore, are still the courses which give the important training. Men soundly disciplined in the fundamentals, whether of social science, natural science, or of the languages, can rapidly adapt themselves to the practical application of their knowledge.

It goes without saying that few courses of any of the three great divisions of the college—the Humanities, the Sciences, and the Social Sciences—have escaped entirely some change of emphasis or of content wherever that will make them more valuable under present conditions. The twenty-five departments of instruction have deposited with the Committee lists of the courses which they consider especially pertinent to the current situation. And advice will be freely offered to any student as to how he should choose among his electives those which in his case will be truly "defense courses."

Together with these changes the Committee has added to the curriculum seven emergency courses. Four of these are short cuts to definite technical skills. A course in Map Interpretation, which is indispensable for certain aspects of national defense, treats of maps and their uses, emphasizing contour maps and aerial photographs, making use of various Army manuals designed for the training of officers in map reading. A course in Mathematics, for Juniors and Seniors who can devote only one year to Mathematics, is offered to meet the individual plans of men intending to enter a particular field; for, in addition to the needs of mathematics in industry, there is scarcely a branch of the Army and Navy services which does not demand some mathematical training.

A bulletin from the National Research Council stressing "the urgent need of men who have specialized in radio communication and electronics" has been partly responsible for a special course in Physics in this field, where the details of the course will follow, so far as they can be ascert ained, the needs of the armed services. A practical course in Psychology, Tests and Measurements for Military Personnel, will give students the basic groundwork, with particular emphasis on the kind of testing which they might encounter in the military services, where this feature of personnel placement is so highly developed.

Three of the courses are in the realm of the ideological. Components of Democratic Thought, limited to seniors, attempts a philosophical and historical integration in the minds of the students of the ideas implied in the contemporary conceptions of democracy and freedom, reminding them that these ideas have so distinguished and so extensive a history in human experience that there is a strong presumption of their absolute truth. It is an experiment in corporate thinking, and representative members of the faculty will lecture and also conduct in small sections discussions relative to their lectures.

The two remaining courses are in the field of Political Science. Explain it as we may, America has always insisted upon living in a world which does not exist. Recently there has been an increasing demand that America face reality; that the colleges do their part and give serious attention to power politics and the relation between military strategy and national policy. To handle these topics two competent authorities have been called to the campus: John Pelenyi, until recently Hungarian Minister to the United States, who will conduct a course in Power Politics; and Dr. Bernard Brodie, of the Princeton Institute /or Advanced Study, author of "Sea Power in the Machine Age," even now going through the reviews, who will lecture on Modern War Strategy and National Policy.

Hemisphere defense demands greater enlightenment on the subject of inter- American relations. Good-will missions have worn out their welcome. Factual knowledge must replace romantic misinformation if we are to make any headway against the thorough Germans. To cooperate with the Romance Department, Professor Isaac Joslin Cox of Northwestern University, an outstanding authority on Latin America, will be at Dartmouth during the first semester for public and class lectures and especially for student conferences.

These seven courses are not open to freshmen. But the first year class has not been neglected. For the one course in social science formerly required of all freshmen (Social Science 1-2) the Committee has substituted courses in economics, history, political science, and sociology and permits a second elective from this group. This action secures flexibility in the first year. English alone is now the one course specifically prescribed for all freshmen. Consequently the freshman has greater freedom to prepare himself in face of the emergency for the long-term and the shortterm view.

The press has widely publicized the proposal of a three year course for the A.B. degree. This speed-up, in some cases, would enable students to obtain their college degrees before reaching the age for Selective Service. Such has always been possible in theory and in practice at Dartmouth, and the requirements for the degree can be completed in three years by securing necessary credits during the summer and by taking six courses during the four semesters of the second and third years. This possibility was reaffirmed in July by a vote that a student who considers it necessary, in view of the national emergency, to secure the A.B. degree in less than the usual four years may be granted permission to do so on the approval of the Committee. However, in spite of press reports to the contrary, the idea of a three year course has not found favor among the traditional liberal arts colleges and the privilege will probably be infrequently requested. Nonetheless the College, facing an unpredictable future, stands ready, here also, to adapt itself to any compelling circumstances which may develop.

To encourage diligence and awareness of the national need, the Committee has announced that sophomores, juniors, and seniors may elect a sixth course without payment of the customary fee of $45.00, provided the extra course is taken for national defense purposes and not to make up scholastic deficiencies; and that, under the same circumstances, change of courses may be made up to the opening of College without the customary penalty. During the summer the Committee has held open office daily to furnish advice and information and has answered letters of inquiry from our widely scattered student body.

Another point should be stressed. The presence of Thayer, Tuck, and the Medical School on the Campus affords the Dartmouth undergraduates, in this sylvan retreat, the opportunities usually available only at an urban university. Few liberal arts colleges so situated geographically can offer similar advantages. These Associated Schools, providing advanced courses in medicine, engineering, and production management, all give professional training of such vital importance to the nation as to place the student in the category of "necessary men" by many local Selective Service boards and therefore eligible for occupational deferment.

In the year past there has been much activity among Dartmouth men in regard to military service. Advice and help have been extended by many offices and many individuals. In the Army Air Corps, the Army is grouping its Flying Cadets in college units during the training period, and a Dartmouth unit has recently been formed. The same holds for the Naval Reserve Aviation Cadets. A number of Dartmouth graduates has been accepted for special training as meteorologists and weather forecasters for aviation with the armed forces. In the Naval Reserve V-7 class, for the Ensign commission, the Navy, in 1940, enlisted Dartmouth undergraduates under a plan that allowed them to complete their college course. Six of the seven members of the 1941 graduating class of Thayer School have been commissioned as Aviation Specialists and have been called to active service as engineers with the Navy Air Corps. Six men from the first- year class of Thayer School and one member of the Junior class in the College have also been commissioned as Aviation Provisionals and will be permitted to complete another year of college work before being called to active duty.

The Marine Corps Reserve enlists men only through the colleges and Dartmouth has filled its quota of sophomores, juniors, and seniors. Civilian Pilot Training enrolled 40 undergraduates during the past year and ten others are taking the summer course. The White River Junction airport makes flight instruction possible within five miles of Hanover.

Since the Army has announced its plan of incorporating ski patrols, the national military organization may benefit from the expanded program of professional ski in- struction which Dartmouth offers for 1941-42. A director of recreational skiing will provide interested undergraduates with the expert instruction previously available only for the ski teams. In this way the College hopes to make further contribution to military defense.

The College published and mailed to all the students and their parents in July a Dartmouth College National Defense Bulletin of twenty-four pages of information and advice, which received favorable notices in many quarters. W. A. Macdonald, who devoted his entire two-column "View- point on Education" of The New YorkTimes of July 20 to excerpts from it and comment, concluded: "That is a guide which might profitably be read, marked, and learned." Another, briefer, DefenseBulletin went out to the three upper classes in late summer.

Space doesn't permit to tell of the valu able work for defense industry which has been done, and will be continued, by Thayer School and Tuck School in the tuition-free Defense Training Courses sponsored by the United States Office of Education. But enough has been written to indicate that the College is alive to the crisis and organized to meet, for the good of the Nation and of its students, whatever lies ahead. It is fortunate in the leadership of a President who has played an important role, national and academic, in two world emergencies and won the admiration and confidence of all with whom he has come in contact. It is fortunate in a faculty which is competent and eager to make the maximum contribution to the public good. It is fortunate in the loyalty of its alumni, who have been helpful in advice and consistently unselfish in financial assistance. It is no less fortunate in its undergraduates, who are showing them- selves not inferior in intellect or in spirit to any Dartmouth generation of the past.

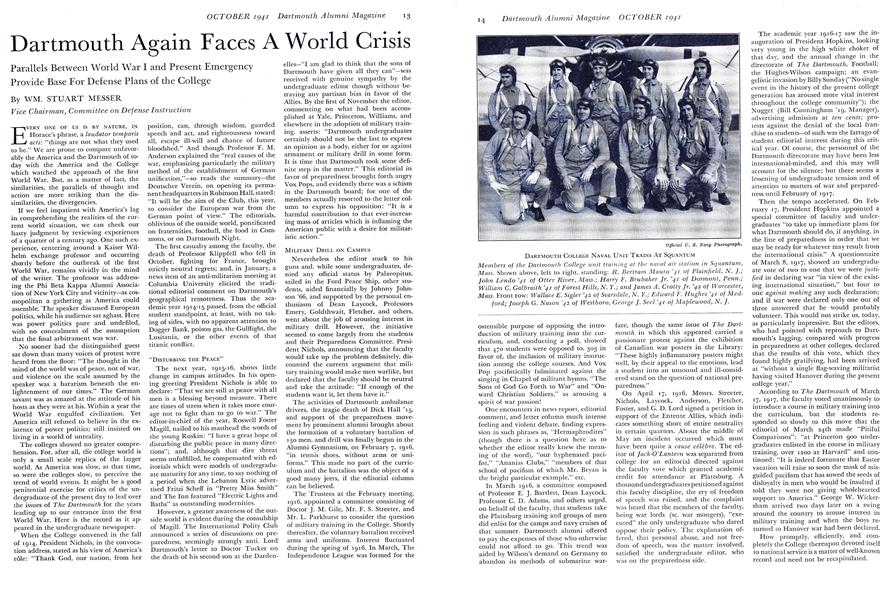

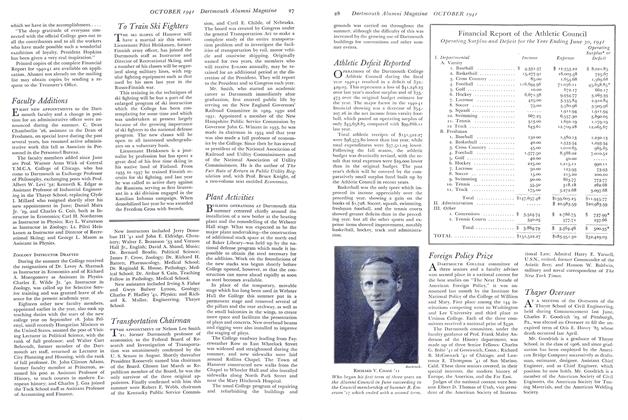

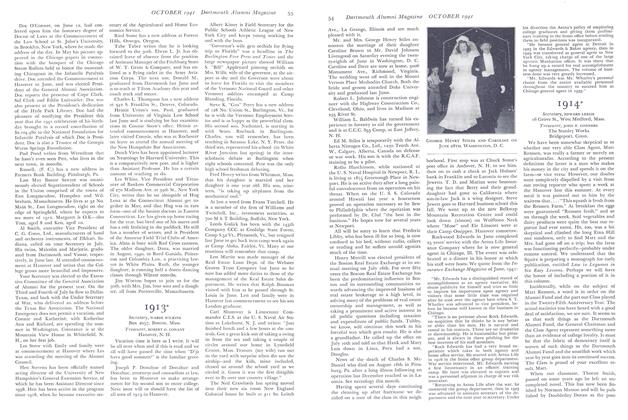

DARTMOUTH COLLEGE NAVAL UNIT TRAINS AT SQUANTUM Members of the Dartmouth College unit training at the naval air station in Squantum,Mass. Shown above, left to right, standing: R. Bertram Mauro '41 of Plainfield, N. J.;John Lendo '41 of Otter River, Mass.; Harry F. Brubaker Jr. '41 of Dormont, Penn.;William C. Galbraith '41 of Forest Hills, N. Y.; and James A. Crotty Jr. '42 of Worcester,Mass. Front row: Wallace E. Sigler '42 of Scarsdale, N. Y.; Edward F. Hughes 41 of Med- ford; Joseph G. Nason '42 of Westboro, George J. Seel '41 of Maplewood, N. J.

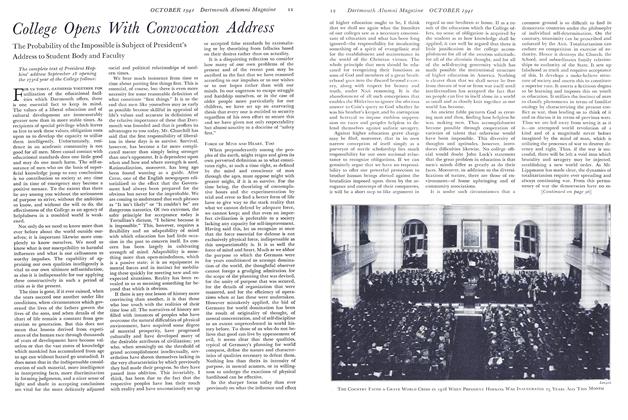

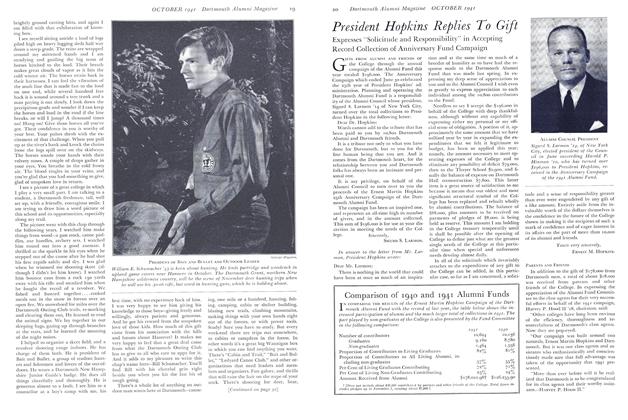

OFFICERS OF THE COMMITTEE ON DEFENSE INSTRUCTION President Hopkins (left) is chairman of the faculty-administrative committee appointedby the Board of Trustees to take action in its behalf in relating the curriculum of theCollege to the emergency of national defense. Prof. wm. Stuart Messer (right) is vicepresident of the Committee on Defense Instruction and is author of the accompany-ing article "Dartmouth Again Faces a World Crisis."

CIVIL PILOT TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES FOR DARTMOUTH STUDENTS Operating from the White River Junction airport, and guided by Dean Frank W. Garranof Thayer School and Prof. Richard H. Goddard of the Department of Astronomy, threegroups have completed the C. P. T. ground and flying course. M. E. Traylor Jr. '44 ofWellesley Hills, Mass., is shown above in a Cub training plane. He was one of 9 undergraduates who completed the course this summer. Groups of 20 and 21 earned their CPTwings the first and second semesters of last year, and the capacity enrollment of 20 begantraining with the opening of College last month.

Vice Chairman, Committee on Defense Instruction

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleFavorable Financial Year

October 1941 By Alumni Fund and Over Two Millions Added to Assets -

Article

ArticleCollege Opens With Convocation Address

October 1941 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

October 1941 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912*

October 1941 By CONRAD E. SNOW, RICHARD C. PLUMER -

Article

ArticleOut-Of-Doors Disciple

October 1941 By ROSS McKENNEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

October 1941 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR

WM. STUART MESSER

-

Books

BooksMAGIC SPADES

FEBRUARY 1930 By Wm. Stuart Messer -

Books

BooksTHE COMPOSITION OF THE PSEUDOLUS OF PLAUTUS.

APRIL 1932 By Wm. Stuart Messer -

Books

BooksTHE CULTS OF ARICIA.

February 1935 By Wm. Stuart Messer -

Books

BooksAN ECONOMIC SURVEY OF ANCIENT ROME

November 1938 By Wm. Stuart Messer -

Books

BooksTHEMES IN GREEK AND LATIN EPITAPHS

November 1942 By Wm. Stuart Messer -

Article

ArticlePLANS FOR SERVICEMEN

November 1944 By WM. STUART MESSER