PETER M. KEIR '41 SPEAKS FOR CLASS AT COMMENCEMENT

DURING THE PAST FEW MONTHS we seniors have been suddenly sobered by the realization that graduation brings to an abrupt end the pleasant way of life which we have been following for the last four years. More than ever we have begun to ask ourselves questions—questions that center principally around two poles of thought. One—What exactly have we gained from the opportunities offered us at Dartmouth? and two—How in a future that at the moment forbodes little but adversity, can we best utilize what we have gained?

The answers to these questions are elusive. When one has lived through an experience like college, it is difficult to make the words describing that experience anything more than inadequate symbols of deep feeling. Nor in transitory times like these is it easy to devise a plan of action for the future. Still if our education at Dartmouth is to assume the place of importance in our lives that it should, we must make a definite effort to answer both of these questions.

Each of us in the class of 1941 has acquired something different from college. It would be impossible for me to know—much less enumerate here—all of these gains. Yet there are at least two general convictions to which I think almost all of us would adhere. First, we believe that the individual is worth something in himself and should have a voice in making the decisions that shape his existence. Secondly, we believe that for men to make the most of their potentialities they must work together constructively—even though at times this means sacrificing part of their individual freedom. This includes not only men as individuals, but also men banded together in employers' associations, labor unions, and nations. It precludes such restrictive man made ideas as high tariffs, race prejudice, price fixing that restrains trade, and especially the destructive force of war.

Today we are graduating into a world quite different from what we learned it ought to be. We were never so naive to believe that it was or that it ever would be entirely what it ought to be, but it does come as quite a shock to find many of our beliefs being negated every day. Many of us are having our lives shaped without our say, race prejudice is rapidly gaining adherents, and the same men who told us war was terrible now tell us to go fight one.

Confronted by this paradox there should be no wonder that we are confused and hesitant when we try to apply what we learned from college to our living in the future.

As a class we seem to be following two divergent plans of action in our attempts to eliminate confusion.

There is one group which seems for the most part to have repudiated what they learned in college as false and as not applicable to their present situation. This group has adopted a fatalistic attitude toward living, feeling that their future has been ordained by powers beyond their control. Their answer is to live completely and selfishly for the few moments remaining before conscription—the few moments remaining before the apparently inevitable war into which the leaders of their State seem so eager to plunge them.

In this attitude there is great danger, for its proponents seem to have denied that there is anything left in the world to believe in. They have placed the right of their individual desires above all else and twisted the meaning of democracy into a resentment against control of any sort that interferes with these desires. Were this attitude accepted as a national formula, the resulting confusion would be catastrophic. It would be a direct invitation to the opponents of democracy to fix a more rigid control over all our lives.

There is a second group in our class which has not lost faith. They accept the present world conditions as a challenge and are trying hard through constant reference to experiences gained from college to determine what their individual action should be in helping to shape national policy.

As students who have received greater educational opportunities than the majority of Americans, it is the responsibility of all of us to take an active part in the solution of present day problems. It is true that our college learning has not supplied us with many answers to these problems. That is not its purpose. It has taught us the methods to follow in seeking the answers, and it has given us the historical perspective needed to maintain our balance.

In accepting the responsibilities of active citizens in a democracy that is trying hard to remain a positive factor in a world largely hostile to it, we do not accept an easy task. Yet if we are willing and determined, it is not a hopeless task. We know that we want to keep the power to shape our own lives and to live in a world where men at least try to work together.

If we back these convictions with a faith that we can succeed as strong as the faith which now carries our opponents to triumph—we will succeed.

Conscription—even war—does not mean the end of our world. Some of us may not live to see success. If our efforts are united and willing, many of us can live to see success. Therefore, let us not abdicate responsibility of living only in the present. Remember that unless we—the so-called college men—use our greater background to work out a solution of our present problems, we can hardly expect anyone else to do so.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

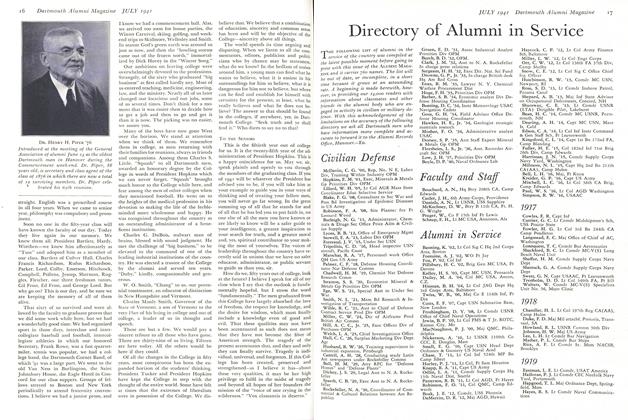

ArticleDirectory of Alumni in Service

July 1941 -

Article

ArticleBaccalaureate Hits Hypocrisy

July 1941 -

Class Notes

Class NotesFifteenth Reunion of 1926

July 1941 By ROBERT E. CLEARY -

Class Notes

Class NotesThe Tremendous 20th

July 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR. '21 -

Class Notes

Class NotesSuper Twenty-Fifth of 1916

July 1941 By FLETCHER R. ANDREWS -

Article

ArticleCommencement Closes 172nd Year

July 1941

Article

-

Article

ArticleTimely Tid-Bits

JANUARY, 1927 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Trustee Nominated

JANUARY 1929 -

Article

ArticleStage Student

February 1941 -

Article

ArticleThree Centuries of Water Over the Dam

Jul/Aug 2004 -

Article

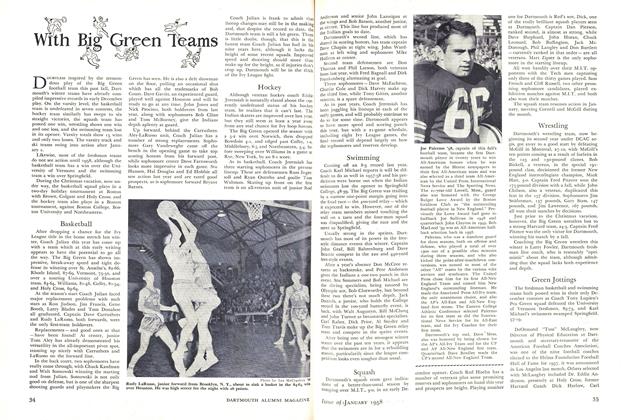

ArticleBasketball

January 1958 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleWinter Sports Need Transfusion

FEBRUARY 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS