COLLEGE GENERATION OF TWENTIES SPEAKS TO GENERATION OF FORTIES

IN A FALL ISSUE of the Harvard Alumni Bulletin there appeared an article "TwentyTwo Speaks to Forty-Txoo" written by HarleyC. Stevens, University of California '22. DavidMc Cord, editor of the Harvard magazine,believed that the said article should be aswidely distributed as possible. We agree, andhereby print an abstract of same.

.... My generation believed in the Treaty in 1920; most of 11s believed in the Covenant and the League. I shall remember always President Wilson, ill, broken and dying, coming to the Greek Theatre in the fall of 1919 to make a last plea for ratification. To us who were there in force, he still seemed a sign and a symbol of a new and better day; and what he said filled our hearts with unutterable longing and our minds with an intolerable ache. Our elders pointed out the Treaty's faults; we were not impressed. We wanted to take the risks involved in building a world in which democratic institutions would not only be safe, but would flower and demonstrate a creative power that would lead all men to wonder and to emulation.

This dream, this vision, evaporated before our eyes by a process that left us all deeply disillusioned. It became enmeshed in partisan politics and involved in absurd disputes. It was pulled to pieces by legal fingers. There were the reservations and manifestos and the

"Yes, buts—lt died, in the last analysis, not because of evil and scheming men, but because the whole society of which we were a part let it die.

First, and apart from all issues and dilemmas, we must fight and win this war completely and without reservation. This is not intended as a spreadeagle statement. But unless we do that, all I shall have, to say hereafter is without meaning or validity. With all our faults and shortcomings, we are as a people and as a nation, concerned with freedom and equality. And however feeble or ineffective our Christian culture may be or have been, we have not denied, as our opponents are driven to do, the quality of individual love and individual obligation which must restrain the heads or engineers of any universal system—the one thing which alone can change a dictatorship into a brotherhood; which alone can differentiate a man from a slave. Rather we are challenged by this war to seek out fundamental laws to guide us and to ask: "What of the peace and the future?"

This time it may be different. I say "may be" because the generations now fighting will have something to say about it. And it seems to me that the real problem is not whether the world wants peace, but whether it is willing to adopt measures necessary to that end. Some of these measures must and will be economic and political in character; some will be beyond economics and politics. It is of these latter I would speak.

It is precisely here that the University and its younger graduates come in. For the University must offer its graduates, and they must get, an education which gives more than a mastery of facts. It must get at their own souls. Students and teachers must appreciate that over against the specialized teaching of men for banking, for scholarship, for industry, for art, for medicine, for law and the like, there is a general teaching of men for intelligence in the conduct of their own lives. Sharper tools have conspicuously failed us. What the University must give and what its graduates must constantly strive toward is the wisdom that comes from a heightened perception of human values—the power wherever man goes of being able to see in any set of circumstances, the finest response which a human being can make to those circumstances.

Some few but difficult things you must do for your own and ultimately the world's salvation, and so that you may be ready to cooperate with those free and benevolent minds wherever they may be, who dream with you of a brighter day. I think the most penetrating observation that has been made of your generation, and it comes from one of you, is that you entertain a deep seated uncertainty about all ideals and all absolutes. Now I appreciate that this is not wholly your fault, though you are not without fault; but the danger is that you cannot survive in a world where millions of men and women, including your contemporaries in other lands, whether mistakenly or not, at least have found principles to which they have given their impassioned assent and for which they have been willing to die and have died. And even if you were not faced with this danger, your position now and in the future would seem to me to be precarious for your inability to find your own way to the acceptance of any ideal leads to paralysis and futility. It is all very well to be suspicious of moral absolutes, but it is important many times, to recognize a moral issue when you see it.

If I may say so your first job is to understand and accept your obligations as men and women of independent mind. As I have heard some of you state: you have assumed to do your own thinking, to find your own God, to accept or reject any and every belief, to take nothing on the say so of your elders. Well and good. Then learn, at all costs, something about the ultimate nature of man—that there coexists in every human heart conflicting and often mutually exclusive desires, that man must choose in order to act at all, that therefore each hour of a man's life is an hour of crisis and decision, and that the sum of his choices defines his character and determines his fate. Learn something about history, which is memory and the record of what man has achieved and done. Learn something about religion and philosophy and literature, which are the garnered interpretations of experience that teach man how to live. No man has much right to life, let alone education, if he is not willing to seek out the fundamental purpose, the ultimate ideal toward which he lives. It is right and necessary, as the great Holmes has said, that you should lay your course by a star you have never seen and may never see; that you should dig by the divining rod for springs you may never reach.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

March 1943 By Dartmouth -

Article

ArticlePresident Explains Navy Relations

March 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

March 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Article

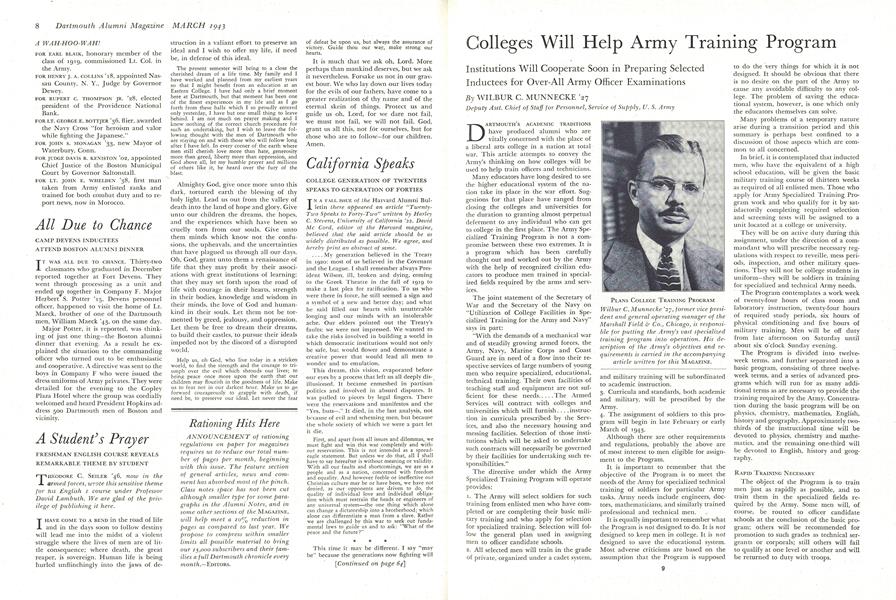

ArticleColleges Will Help Army Training Program

March 1943 By WILBUR C. MUNNECKE '27 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923*

March 1943 By SHERMAN BALDWIN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932*

March 1943 By CARLOS H. BAKER

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT NICHOLS AMONG THE ALUMNI

March, 1914 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

JANUARY 1929 -

Article

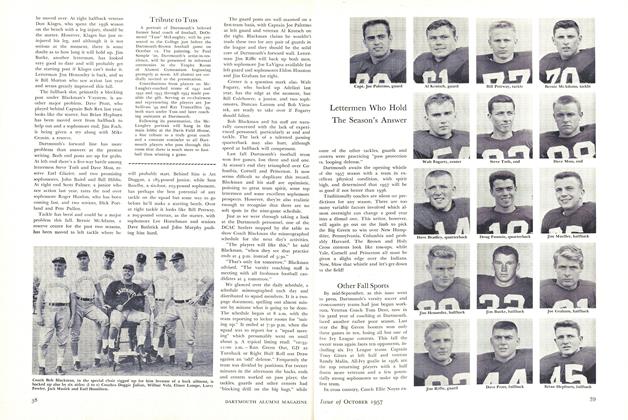

ArticleTribute to Tuss

October 1951 -

Article

ArticleSome Misapprehensions in Regard to the Selective Process

February, 1931 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

ArticleGreater Boston Alumni Sample Florentine Culture

February 1974 By WALTERS. YUSEN '58 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

FEBRUARY 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER