1 4 Wheaton, 517. 2 There were only six present, since Mr. Justice Todd was absent throughout the term because of illness. The decision was 5 to 1, Mr. Justice Duvall dissenting, without opinion.

3 Corroborated by Webster. See John Wentworth, Congressional Reminiscences, 1882, p. 44. 4 The Yale professor's letter says "for more than four hours."

5 Original letter in Library of Congress. Letters herein quoted the location of which is not indicated are in the Baker Memorial Library, Dartmouth College. The original subscription, by Hale and seven others, to Wirt's fee of $2OO has been preserved. Tempora mutantur.

6 But see the "Stop Press News" at end of this paper.

7 In the Webster papers, Library of Congress.

8 And this is the Story who writes in his opinion (4 Wheat. 713): "It is not for judges to listen to the voice of persuasive eloquence or popular appeal"! 9 Neilson, Joseph: Memories of Rufus Choate, Boston, 1884. A letter by "M.C." of March 14, 1818, in the Dartmouth Gazette, March 25, 1818, says: I heard a part only of [Webster's] speech. . . .Hewas not only acute, elegant, and argumentative, but,what is very surprising in such a case, he was pathetic. .Judge was obviously moved, and couldnot conceal his emotion.

Clearly Marshall.

10 Congressional Reminiscences, John Wentworth, 1882, p. 44, also corroborating Goodrich that the Court met in a "mean and dingy building."

11 Letter in the library of the New Hampshire Historical Society. In justice to Webster, it should be added that part of the letter is missing.

13 Students of how the Supreme Court functioned under Marshall will be interested to know that its files—today, at any rate,—contain no notes or copy of Webster's argument, and no "brief" from either side. The red-tape school will shudder that there is not even any record that Webster was admitted to practice before the Supreme Court. The justices must have had a hard time in this case, where they were too moved to take their own notes. The reporter had an equally hard job, mechanically. A letter from Wirt to Webster (Library of Congress) shows that even a year later, April 24, 1819, Wirt was so harried that he had no time to write out his argument for Mr. Wheaton, but merely could send him the notes he had made, which is one explanation why Webster bulks so large in 4 Wheaton. "My argument was framed under great disadvantage, having to prepare it very hastily and under the pressure of official business which was wholly new to me," Wirt says, confirming his "crammer," Mr. Hale, and the court records. Indeed, he made such an apology to the Court (Letter, Webster to Mason, March 13, 1818, Private Correspondence ofDaniel Webster, 1857, Vol. 1, p. 176).

13 Although in this letter Webster states that "these precautions were taken to avoid the indecorum of publishing the creature", on September 9, 1818, he writes to Mr. Justice Story the following, amazing from modern ethical standards, but perhaps not to be wondered at in days when there were neither printed "briefs" nor stenographic court reporters: I send you five copies of our argument. If you sendone of them to each of the five judges as you thinkproper, you will of course do it in a manner leastlikely to lead to a feeling that any indecorum has beencommitted by the plaintiffs. The truth is, the N.H.opinion is able, ingenious, and plausible. It has beenwidely circulated, and something was necessary to exhibit the other side of the question.

14 The opinions were announced in time to be included in the book as finally printed, which explains the "February, 1819" date on the title-page.

35 The book is still technically "in print." A decent surplus of the original copies was recently discovered. This must be an American record—still in print after almost 120 years!

18 The argument as reported in 4 Wheaton is taken from Farrar, with the quotation from Cicero. A manuscript by Webster in the Baker Memorial Library approximates the form of Farrar and Wheaton; it has no peroration.

17 The letter is in the hand of an amanuensis, but is signed and addressed to Choate by Goodrich, and contains a few corrections in Goodrich's hand. Other existing letters by Goodrich at this period are in his secretary's hand, and there can be no doubt whatever that the letter is Goodrich's composition.

M Ohoate tampered with his "text" somewhat. The passage beginning "the court room" at p. 38, and ending "history of eloquence" on p. 39, is in Choate's hand, i.e., is an interpolation. One passage from the letter is removed to another place, and there are a few minor changes, none of which affect the text materially. The "familiar quotation" is exactly as Goodrich's secretary wrote it for him.

10 The pamphlet sold well. There was a reprinted edition of 88 pages by the same publishers in the same year. Its title-page reads "Eighth Thousand" instead of "Printed by Request," and the errors "Fort William and Mary" on p. 10 (always corrected in pencil in the 100-page edition) and "August, 1796" on p. 12 (sometimes so corrected) are changed to the correct "Fort William Henry" and "August, 1797."

20 Goodrich's letter. No Mr. Goodrich was present at Exeter, N. H., and we have no real knowledge of what Webster said. Jesse F. Orton, in "Dartmouth College Case," Independent, Vol. 67, 1909, pp. 392-7; 448-53, says that the tears were caused by the same peroration that Webster used at Washington six months later. He cites no authority. (Weeping or not, the judges decided against Webster and the College.) The American Law Review, Vol. 46, pp. 667-8, in an article by the eminent scholar, Charles Warren, quotes a "contemporaneous" account in the Salem Gazette, the original of which I have not seen: Though upon a mere question of law arid strictlyconfining himself to his subject (quaere), yet by thegenius and eloquence of his soul, of sublime sentimentand feeling—with which he presented his views ofthe cause, he swelled the hearts and filled the eyes ofmany who listened to him with delight.

Perhaps the same conclusion can be read between the sarcastic lines of that University organ, the NewHampshire Patriot, Oct. 7, 1817, after saying that it has "no' particular information": It is said, however, that Mr. Webster, upon whommuch dependence may justly be placed in all mattersof palavering and possibility, replied to the arguments of Messrs. Sullivan and Dartlett, in an eloquentspeech of an hour's length, concluding with a verypathetic appeal to the court as alurrmi of the collegelIn this case, however, it is thought that the pathoswas misapplied.

The tears are not wholly belied by a letter from Levi Woodbury to Governor Plumer, Exeter, Sept. 19, 1817 (N. H. State Library). The case was "elaborately and eloquently discussed," says he; "we have had, however, more language than iight." Webster's own remarks to his co-counsel, Jeremiah Mason (letter, N. H. Historical Society) are severely practical: It would be a queer thing if Gov. P.'s court shouldrefuse to execute his laws. I am afraid there is nogreat hope of their disobedience to the powers thatmade them.

21 The Goodrich family papers were carefully preserved for many years, but were unfortunately destroyed by fire, except for a period having no bearing on this story, in 1919. The copy of the 1853 pamphlet which Choate presented to Goodrich is at Dartmouth; there is not a mark on it significant to this subject.

22 The translation is another Choate addition. Goodrich's letter stopped at "fili."

23 Hale's letter to Plumer of the same date says that Wirt "made Webster lower his crest and flit uneasy."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDaniel Webster and Dartmouth

April 1943 By CARROLL A. WILSON -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1943 -

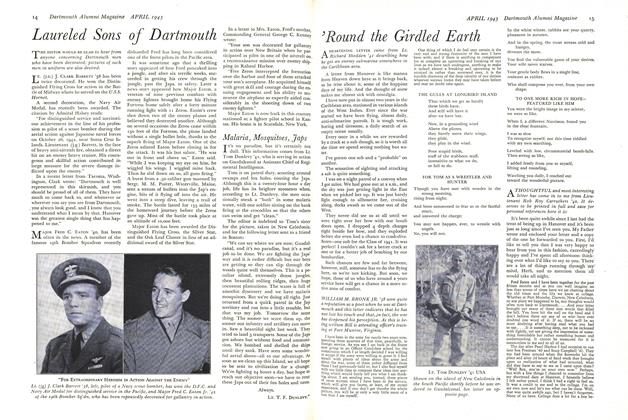

Article

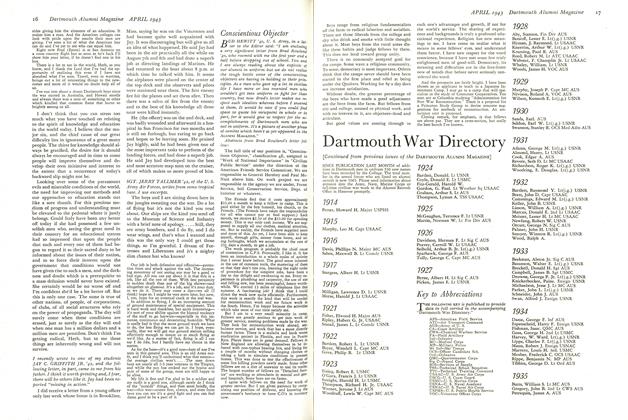

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

April 1943 -

Class Notes

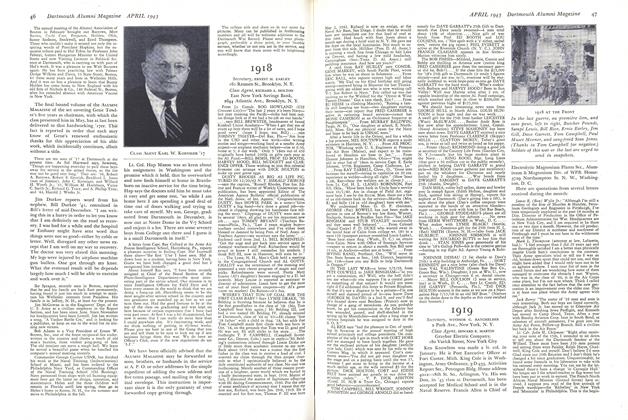

Class Notes1918

April 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

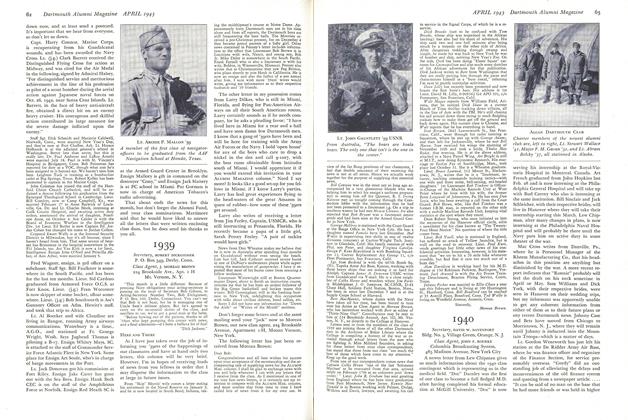

Class Notes1939

April 1943 By ROBERT DICKGIESSER, J. MOREAU BROWN -

Class Notes

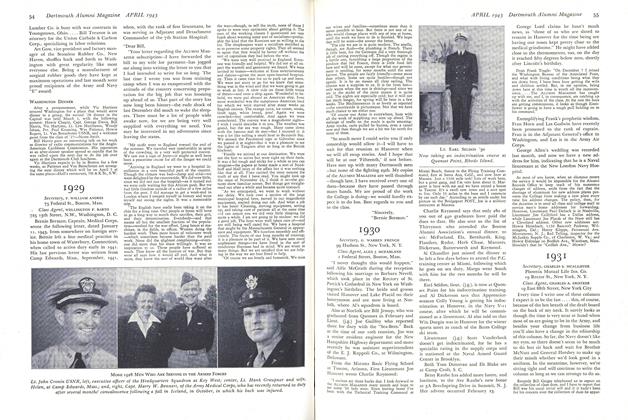

Class Notes1931

April 1943 By CHARLES S. MCALLISTER, CHARLES A. GRISTEDE