New Religious Program Recalls Early Basis of College

IN FURTHERING THE TEACHING and application of religion the present administration of Dartmouth is true to the College's permanent tradition. Professor Leon B. Richardson, climaxing his analysis of the creative personality most responsible for designing the modern Dartmouth observes: "Dr. Tucker's appeal was for the recognition of religion as the central element of life." From the beginning of his presidency William Jewett Tucker stressed that note. His inaugural address in 1893 declared: "The college performs an office which, I take it, no man will question as it translates the original and constant re- ligious impulse into terms of current thought and action, making itself a center of spiritual light, of generous activities, and, above all, of a noble and intellectual religious charity."

Eleven years later, upon the occasion of the visit of the Earl of Dartmouth for the laying of the cornerstone of the new Dartmouth Hall, the President stood at the grave of the founder of the College and said: "The gift of the eighteenth century to the colleges of America was the religious spirit The religious spirit was the great educational endowment, and it was very great, because it was creative. It took possession of fit men and taught them to lay foundations upon which men and states might afterward build securely and bravely." In mature evaluation of the long span of Dartmouth's years Dr. Tucker, a decade after his retirement, reverting again to Eleazar Wheelock wrote: "To him the college owes its existence because he was an embodiment of the spiritual influences of his generation..... What is termed the romance of Dartmouth is in truth a spiritual romance The religious motive not only acted with peculiar intensity in the inception of Dartmouth, but it gave to the movement a certain adventurous character."

All will agree that whatever else Dartmouth has been it has been adventurous. Upon further consideration one may well conclude with Dr. Tucker that the adventure began in religion and extended to education and other fields. Nearly all the early presidents and large numbers of their faculties were clergymen. Older alumni today recall the lasting impression made by President Tucker's chapel talks; the next generation of alumni remembers likewise the continuation of this tradition in the brief but carefully prepared and amazingly clear chapel addresses of President Nichols or in the freer, man-to-man chapel speeches of his associate, Professor Benjamin T. Marshall. Many of us date our first real acquaintance with the classic prayers of the Episcopal liturgy to their chaste reading by Dr. Nichols, and if our religion has in it anything of the liberal and dynecessity namic we owe much of this quality to the lecture classes of Ben Marshall, into which for several good reasons swarmed close to one hundred of the men of the College, including athletes and other major figures.

The first world war and its aftermath wrought many changes, but the College authorities who have carried on during this period have in the new environment perpetuated the religious tradition. Frank L. Janeway, Ambrose White Vernon, Roy B. Chamberlin, and William Hamilton Wood have been among those associated with the religious program under President Hopkins. Throughout the years Dr. Hopkins has stressed the spiritual aspects of college life. He recently reiterated his determination that religion should regain its power "to produce conviction and faith such as dominated the minds of the founders of the College." The interest which the alumni maintain is manifested by Mr. Marden's thoughtful editorial "Religio Collegii" which by happy coincidence appears in this issue of the MAGAZINE.

The fact that Professor Wood reached the retirement age this year suggested readjustments in what had been one of the last remaining examples of that independent entity once so common in the colleges, "the one man department." Today's tendency integrates such departments into larger groups. It was decided, therefore, by President Hopkins and Dean Bill to broaden the offerings and personnel, reasserting with an eye upon the post-war world the of a religious emphasis as a central part of college life. The oldest endowed Dartmouth chair, dating back to 1789, is the Phillips Professorship of Divinity or Theology, named in honor of John Phillips, pioneer trustee and benefactor. Mr. Marshall and Mr. Wood held it under the title of Phillips Professor of Biblical History and Literature; since July 1st I have occupied it as Phillips Professor of Religion. I come to this responsibility directly from fifteen years as a professor of history and international relations in American colleges. My approach to the teaching of religion naturally is dominantly historical. To serve as Assistant Professor of Philosophy and also to aid in presenting religion from the philosophical angle, the administration added to the Dartmouth faculty on November Ist an effective and versatile Scottish scholar, Dr. T. S. K. Scott-Craig, a graduate of Edinburgh University with graduate study also at Zurich and Tubingen; coming to the United States nine years ago, he has taught in two theological seminaries and one college in this country. He and I form the congenial nucleus of a faculty team which aims to continue the teaching of religion to Dartmouth students in a liberal and normal way, remembering always President Tucker's injunction that instruction in this subject "must not fall below the intellectual level of the college." We hope that this study may be also as interesting, suggestive, and useful as that in any other academic field.

Through the courtesy of the library authorities, the Department of Religion has been assigned an attractive suite on the second floor of the Baker Library, looking out upon the chapel and immediately adjoining the comfortable quarters of Robert Frost. Here we hold seminars and small classes and maintain what we trust may become recognized as an appropriate, center for the study and discussion of religion. During the summer term I conducted here on Monday evenings a non-credit seminar in which both faculty members and students combined to discuss the issues raised in recent religious books. During the present term the discussion group will be for students alone, except for the faculty guide, with topic and hour arranged by the students themselves.

The most important formal work is naturally the credit courses in religion. A series of electives, some repeated each year, some in alternate years, has been arranged after a study of the local situation and of the patterns worked most successfully in other colleges. George F. Thomas, formerly a member of Dartmouth's philosophy de- partment and now Professor of Religion at Princeton, .gave valuable suggestions while spending a month in research recently at the Baker Library. Yale, Haverford, and Stanford are among other institutions upon whose experience the Dartmouth plan has drawn.

During the summer my credit elective was entitled "The History and Social Significance of the Major Contemporary Religions." It sought not merely to cover the ground of the usual course in comparative religion, but also to stress the presentday application and potentiality of the various religions. What influence, for instance, has Shintoism exerted upon the present Japanese psychosis, and upon what common grounds may Christianity and the religions of China meet?

With the present winter we swing more nearly into our permanent program. Nothing termed religion is offered to freshmen, but to that class Mr. Scott-Craig gives what appeals to me as an intriguingly original course, "The Modern Mind and Its Heritage." Himself interested in science, he begins with scientists like Julian Huxley and Darwin, social thinkers like John Dewey and Jefferson, tracing their writings, and working backward through earlier roots of some of their ideas. He has sixteen students in this search, a large group for a war-time, non-utilitarian elective. In the spring this course will run back through the origins of Christianity to Aristotle and Plato; in it Professor Philip Wheelwright, Chairman of Humanities, and I will at times assist. This course serves as an excellent, although not required, preparation for the more advanced offerings in philosophy and religion. The basic course in religion under the new arrangement is available to students of sophomore or higher rank. Beginning this fall and lasting through two terms it is taught by me as

"The Foundation, History, and Literature of the Christian Tradition." It examines the origins of the Hebrew religion, shows the influence of other faiths and cultures upon it and upon the Christianity which grew out of it, and traces the impact of Christianity upon civilization down to the present day. An open shelf of reserve books easily available in the lower reading room allows the students to choose intelligently the works most helpful to them. I am this term teaching also a seminar on "Classics of Christian Experience;" at the moment its four sturdy marines and one civilian student, a young pastor, are wrestling with the implications of Augustine's Confessions. Other courses to be given by Mr. Scott-Craig or me later on include "The Development of Religious Thought in America," and "Christian Ethics and Modern Society." In the latter we expect to have the collaboration of Andrew G. Truxal, Professor of Sociology.

It early appeared to me that a great deal of excellent teaching of religion at Dartmouth was being done through courses listed under other departments. Many faculty members in the humanities or social sciences have pursued sound training in religion and have manifested a marked religious influence. Their service to the religious instruction of the College might well be recognized, both for the sake of the student desiring to elect appropriate courses and for the outsider who may examine the catalogue to discover what Dartmouth offers in this field. One would not think of trying to withdraw these men or their courses from the departments which they have long graced, but we have arranged with the college authorities to give such of their courses as are distinctly religious both their regular listings in their original departments and a reference under religion as well. The new catalogue will accordingly contain in our department the English course, "The Bible as Literature," given by Professor Roy B. Chamberlin, Chapel Director; "Philosophy of Religion," given by W. K. Wright, Professor of Philosophy; "Religion and Modern Culture," a sociology course of Professor A. G. Truxal; and Professor George C. Wood's "Medieval Life and Thought," a comparative literature offering noted for its religious implications. The names of these men and of Professor Wheelwright, who in due time will offer a course on "Early Mediterranean Religion," will be listed at the head of the forthcoming catalogue's write-up of the Department of Religion.

This faculty group, meeting together from time to time, may be expected not merely to promote integration and improvement of the teaching of religion and related subjects, but also to form an increasingly potent community of interest serving to perpetuate among the faculty a basic tradition of the College. Informally a larger faculty body of some thirty members, the Tucker Fellowship, meets monthly to discuss matters of interest to instructors of religion, philosophy, and allied disciplines. A number of faculty members fill pulpits throughout the countryside for single occasions or for longer periods.

The teaching and practice of religion are closely associated; they tend to rise or fall together. Upon the practical side, the Dartmouth Christian Union, with Roy Chamberlin as its faculty sponsor, exercises a strong influence. It continues the traditional Sunday deputations, and performs useful social service through Saturday afternoon work trips to help farmers harvest crops or cut wood. Its spiritual center lies in the Sunday evening meetings at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Chamberlin; discussion led by some faculty member and informal singing of hymns, run into a social hour. The Christian Union officers, nearly all of necessity from the Naval V-12 Unit, hold regular cabinet meetings and carry through a wide range of activities, including the sending of delegates to intercollegiate conferences and the maintenance of a small but lively office in two rooms in the rear portion of Robinson Hall. A strong reinforcement to the Union came last August in the person of Miss Margaret Norris, an experienced worker in the Student Christian Movement who left a post in Boston to become secretary to the Union, and thus in a sense successor to the old office of Graduate Secretary of the Dartmouth Christian Association. With fine ability to appreciate the student point of view, and with maturity and wisdom of experience, Miss Norris has made the D. C. U. offices one of the most efficient and attractive centers on the campus.

In my opinion the teaching of religion goes hand in hand with the expression of religion in worship. Hanover is fortunate in having its three churches staffed by ministers of high character, scholarly attainment, and marked facility to express themselves well and to work with college men. Chester Fisk, Leslie Hodder, and Father John Sliney conduct services which are a credit to the College and the community. They draw good congregations from students and faculty; I think they deserve even better. Professor Louis L. Silverman sponsors a weekly service of worship for Jewish students in Rollins Chapel; non-Jewish faculty members share in addressing these gatherings.

At least twice in each term the Congregational and Episcopal churches merge their morning services into a union service at Rollins Chapel, presided over by Professor Chamberlin and addressed by some notable visiting preacher. Every six weeks or so in addition, Naval Chaplain Leon A. Shearer who makes periodic trips from Boston, conducts a chapel exercise especially for the V-12 men but open to others as well. These various gatherings are the only remnant, at the present war moment, of the old Dartmouth chapel. Few would now advise that any college return to compulsory chapel, but some might suggest that the post-war planning of Dartmouth might well consider the possibility of more frequent convocations, some of which would be partly or entirely religious; such assemblies would manifest a sense of college solidarity and would be more easily feasible upon the completion of the large auditorium recently authorized by the Trustees as a building priority. Similar services are reported to have worked well at such institutions as Yale, Princeton, and Cornell; Dartmouth may care to evaluate them as she thoughtfully plans her peace time years. In religion Dartmouth has done good work. Alumni, students, and faculty will continue to build according to the needs of every age upon these sound foundations.

As I walk toward my work in the Baker Library on these clear fall days I often glance at the pinnacle of the graceful tower to observe there the ever-faithful weather vane swinging this way or that, but always pointing somewhere. It represents Eleazar Wheelock seated beside the pine tree, teaching his Indian pupil whose long pipe points to the ground and whose two feathers project jauntily into the breeze. That was the original Dartmouth, when "Eleazar was the faculty," what President Tucker called the embodiment of the creative spiritual influences of the revolutionary age. Others now constitute the faculty, and the bronze Wheelock high above our heads represents us, while the placid Indian stands for the students, not so placid, who successively come before us. We give them much, but I think we can give them even more. It is still true, President Tucker, as you wrote when we were emerging from that other world war, that the romance of Dartmouth is a spiritual romance, imparting to the College a certain adventurous character.

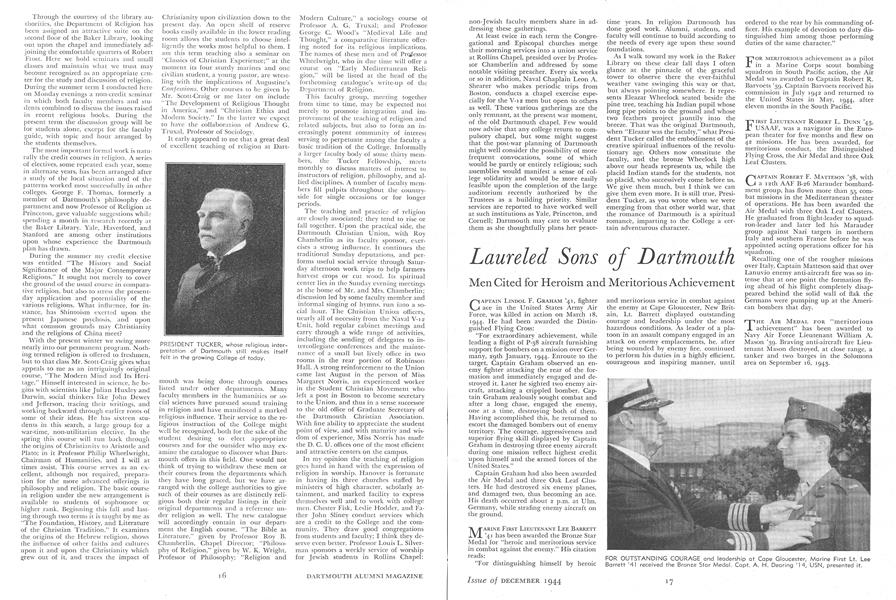

A SEMINAR MEETS under the leadership of Professor Ear! Cranston, center, in the new and extended religious program for civilian and V-12 students. At Professor Cranston's right is Professor T. S. K. Scott-Craig, new member of the Department of Philosophy.

PRESIDENT TUCKER, whose religious inter- pretation of Dartmouth still makes itself felt in the growing College of today.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE FIRST 175 YEARS

December 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

December 1944 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

December 1944 By WILLIAM C. EMBRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

December 1944 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S CHARTER

December 1944 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR