Use of Classroom Movies Steadily Increases at Dartmouth

THIS IS A STORY of growth. The September 1944 issue of EducationalScreen suggests editorially that classroom use of audio-visual aids is, in fact, now reaching "The End of Adolescence"; it is looking forward to a postwar maturity few could have predicted with any great confidence. I shall use this same figure of speech in this article. It is very appropriate that it appear in this issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE because with November 1945, Dartmouth College Films enters a new phase of expansion which many hope will be mature in plan and execution.

The "gestation and infancy" periods of Dartmouth College Films are vague eras, now that we look back on them. The Secretary of the College, Sidney C. Hayward '26, combined his personal enthusiasm for photography with the job of making fuller use of football-game films and the development of movies of the Outing Club for the benefit of alumni and other groups interested in this widely known feature of the College. Dartmouth College Films was created primarily to distribute these films; at that time, President Hopkins' desire to encourage the faculty to use movies as regular classroom aids was secondary to this alumni service. Today the situation is reversed; we continue to film campus activities and important events (the Naval Indoctrination School, the V-12 Unit, the V-E and V-J Day campus celebrations, etc.) to make record of the ever-changing faculty and student-body, and to make such pictures available to the alumni. We have been living through a six-year "adolescence," now coming to a close.

In the fall of 1939, R. Haven Falconer '39 was appointed to be Assistant in Audio-visual Education. The Dartmouth editorialized on October 13, 1939, in defense of this new department "to bring educational films to Hanover." Some misinformed undergraduates protested that this was a dictatorial move to prevent student organizations from showing "movies of their own choice." With the waters calmed by a clear statement of intent, regular notices of "audio-visual shows" in classrooms appeared in The Dartmouth. From the offices adjoining a projection room in 234 Baker Library, Mr. Falconer arranged for educational shorts for an increasing number of courses, and also began to build up a system of distribution of films to New England schools, working with the New Hampshire and Vermont state universities. At that time, he favored the use of films for outside "readings" (as then used by Professor Hinton in Political Science, for example) over more direct use in classrooms for shorter or longer parts of the entire hour. (This emphasis has also gradually been reversed.) Undergraduates were invited to attend any classes where films were scheduled, and to leave after the showing or to arrange small groifps for extra showings in Baker. (Some alumni may also recall an educational experiment which encouraged students to sit in on other courses than those for which they were registered, as suggested by listings in The Dartmouth of lecture or discussion topics for the day.)

In January 1940, Mr. Falconer proposed a course in writing and producing motion pictures—now a commonplace in many institutions. This was tabled at first, but eventually given by Professor Pressey of the English Department. As happened to many other ventures, the war cancelled all such work for the time being. An annual Film Series, reviving some of the better pictures, was initiated in February. The daily notices of classroom films were discontinued because the restricted content appealed to relatively few students and the response was very modest beyond the classes themselves. During this first semester of 1939-1940, nevertheless, just over one thousand reels were shown. Thereafter, "Quality above Quantity" became the slogan. There were ups and downs, misunderstandings, disappointments, and exaggerations (one faculty member was reported to have said that "the movie is the greatest social art form ever seen"); and many successes and failures in the process of making movies available, for whatever they might be worth to the general aim of a liberal education at Dartmouth College, were experienced. The record is there to read in the pages of TheDartmouth for 1939 through 1942, and is etched in the memories of the faculty, students, and staff. The shadow of things to come was seen by May 1940 when the first of many war films was shown. Two other highlights were the establishment of the New England Educational Film Association (NEEFA), and the taking and country-wide showing of the famous Cornell fifth-down game movies in November 1940. Beginnings on a full-length movie to promote college education in general and Dartmouth in particular were made in 1941, but the war prevented any fulfillment of that plan. The many alumni groups who have written asking for upto-date and effective movies to tell Dartmouth's story in high schools and private preparatory schools will, no doubt, have their answers in the not-too-distant future.

The interval between the fall of 1941 and February 1, 1943, was one of gradual slow-down in the full program of Dartmouth College Films. War unrest was in the air, early enthusiasms cooled or even turned to indifference in those who expected too much of the new teaching medium or who had never learned to make the best use of this aid to learning in their classes. In addition, the mechanics of utilizing movies caused some uncertainty or coldness: the early models (like the early radio, automobile, television) left much to be desired and were harder to keep in good working order. Student operators are "students" first and "operators" last: some were good, but others forgot appointments—especially for those early 8 o'clock classes. A final trouble is still with us: the difficulties with the College's 220 DC current to run 110 AC equipment. (Complete change-over to no AC awaits national reconversion of industry and manpower.) For all these reasons, and more, Mr. Falconer and his capable wife and secretary, Mrs. Falconer, and all those who worked closely with them, had their full share of troubles.

"Late Adolescence," a new chapter, began February 1, 1943, when Mr. Falconer left Hanover for New York to do an outstanding job as Director of a Visual Aids Department in the Information and Education Division of the Armed Forces Institute, and Dean Bill asked me to step in and pinch-hit. "For the duration" of course. My intention, at first, was to do little more than meet faculty requests for classroom movies on a stop-gap basis. The Indoctrination School had worked out its own limited program and executed it with little aid from Dartmouth College Films. But with the establishment of the Dartmouth V-12 Unit, a definite about-face occurred. This largest V-12 unit was soon running the largest program of visual aids to classroom teaching in colleges with such units. (Many state universities, through their extension courses, run very much larger programs, of course.) Now Dartmouth was a Navy school and Navy and Marine students were taught the Navy "G.I. way"—which included a strong emphasis on audio-visual aids of all kinds, including classroom movies, indoctrination films, and war-incentive documentaries from Pearl Harbor to Tokyo. (Many will recall the Sunday afternoon in Hanover when we went home from a showing of the German propaganda films Blitzkrieg im western and Drang nach Ostenand heard our radios tell of Pearl Harbor.)

In August 1943 it was agreed that I should work out a close coordination of all uses of visual aids for Navy and civilian classes, Until the V-12 program blended into the Navy R.O.T.C. program, now firmly established with the coming winter term, it was my responsibility to obtain and to maintain adequate equipment and films (and how we shall miss Navy equipment and films now that they are to be less readily available to us), to secure and supervise the work of student projectionists (or do it myself), and to keep adequate records; and behind such glittering generalities, to stimulate faculty members to use more and more visual aids to teaching in Navy classes, and to best advantage; and still farther behind, to pitch in and get the job done by any and all means at hand. (In emergencies, come running; when the Navy beach wagon wasn't available to move a projector where needed, put it in your own car and worry about extra gas tickets later.) In place of a full-time Audio-visual Education Department, my regime has been a part-time labor to be shared with teaching V-12 Graphics for a few terms and fewer hours of teaching in my own department, Psychology. A likely reason why I was chosen to do the job is because I had been active in developing and using a library of slides and movies for my own department, as one of the illustrations accompanying this article suggests.

The armed forces have made such a feature of classroom movies that the phrase "teaching the G.I. way" has become a commonplace. This strong enthusiasm, like that for other innovations, had to win acceptance the hard way. The idea died slowly that movies were only for entertainment and the classroom was not the place for that. As an example, the Director of Training for the First Naval District in Boston had to be "sold" on the value of such aids for Navy classes. In his case, the Visual Aids Officer made a lucky choice of films; he used a Navy film on Celestial Navigation, The Astronomical Triangle. This concept had bothered the Captain in his Annapolis days, but here he found a relatively short and very effective graphic explanation that "sold" him on classroom movies. Not all such movies are that good, or even good at all for all students. There is no magic in the mere fact of movies as such; quite the opposite, in fact, as was demonstrated clearly by those who used classroom movies indiscriminately and watched the students settle down for a short nap as soon as the lights went out for the picture. One classroom-auditorium at a Navy post became known as "Sleepy Hollow."

The first requisite for successful use of classroom movies is the production of firstclass pictures that definitely fill a need not otherwise filled as well. If they are not truly "visual aids to learning" they fall short to varying degrees of justifying their existence and use. The natural and biological sciences are the most obvious courses where movies can be very helpful; the social sciences at present have a fewer number of effective titles. In either case, movies must use "dramatization" with caution; it effectively arouses and holds interests, but it also is easily overdone. The Hollywood touch can bless or destroy, depending on how it is done. No movie audience is more critical than a group of college students. Many business and industrial films can be used with general groups but not in our classes.

The second requisite is a teacher who will give the time and effort demanded for effective use of classroom movies. Each film must be chosen because it can help the teacher explain some technique (use of the Vernier scale), or idea (the concept of Nazi Geopolitik), or demonstrate some facts (structure and function of the eye) more easily and clearly. There is an increasingly excellent library of useful films for the biologist, using such devices as animated diagrams and time-lapse photography and natural-habitat pictures; medical films show actual operations being performed and give each student in a large class a better close-up picture in natural colors than he could get in the operating room itself. Another advantage is that the film can be shown as many times as necessary and whenever and wherever desired.

It must be admitted that, large as our existing film libraries are and excellent as many of the titles have been proven, we are only beginning to make the kind of classroom films needed to fulfill the promise of this medium. Great advances were made during this war by and for the armed forces. In my own department, we would gladly replace most of the thirty titles we own with better pictures: more imaginative, more professionally produced, and more truly instructional. My policy has been to buy a minimum of standard material that will not get out of date and will always be useful; most are rented or obtained without cost. More and more come from business and industry.

Having located the right film for the specific part of a course which presents a problem calling for some kind of aid to effective teaching, the teacher will need to spend considerable time and thought previewing the film and instructions in many cases. The Training Aids Section of the Bureau of Naval Personnel prints attractive Training Aids Guides in a format for notebook filing by instructors. For example, "Swimming through Burning Oil and through Surf" is a life-or-death topic. The Guide gives specifications for the film (size and type, catalog number, time, black and white or color), and then (1) The Purpose, (2) Content (with eight typical shots from the film), (3) Preparation, (4) Points to Look For, (5) a Test on Content, and (6) Follow-up activities. This is a model for civilian teaching, but many will not take the time and effort this requires even when teaching materials are made available. Those teachers who plan courses well in advance and who thoughtfully select and use classroom movies as aids to learning, not as teaching devices in themselves, will obtain real benefit from good classroom movies. The same point may be made for other visual aids: slides, charts, maps, and models.

The marked success of visual aids to learning obtained by the armed forces has put pressure on schools and colleges to re-examine their teaching methods. One article in particular has been given unusually wide circulation. Better Homes andGardens (February 1944) asked the question, "Can Our Schools Teach the G.I. Way?" This article was reprinted by Readers' Digest and by the maker of Victor movie equipment. Several excellent replies were printed but not given equal distribution. For our part, we have seen much of both sides: enthusiasm and doubt, limited budgets and almost complete freedom from counting the cost, smooth and efficient operation and mechanical breakdowns at the worst possible moments. But in general I believe in the considerable value of classroom movies under these conditions: when there is a true teaching problem, when visual aids are available and adequate, when the time involved is not excessive and budgets permit, and when there is no better answer to the problem. Films are aids to learning, and as such are secondary in importance. One of the mistakes of the past, however, has been commercial over-selling of classroom movies by enthusiastic salesmen who describe secondary-school films as being suitable for college classes, for example.

Looking into the future, expansion seems clearly indicated. So far as Dartmouth is concerned, this will be guided by a new full-time Director of Dartmouth College Films, Mr. J. Blair Watson, who takes over on November 1 after his discharge from the Army Air Corps where he continued the training in visual aids he had started at the University of New Hampshire. New equipment will be needed to replace our own aging machines and, more important, the Navy materials which are to be withdrawn with the end of the V-12 Unit. Plans for a coordinating center in the projected new building on the cite of Bissell Hall will be developed, including a revival of production of new films and encouragement of student photography.

This expansion is a general one. Dealers have more orders for movie projectors for schools than they can fill in the immediate future. Hospitals use medical movies extensively. Churches are developing slides and movies of their own and report enthusiastically on the response obtained. My neighbor-in-line at the recent reception to President-elect Dickey was clearly much impressed during a recent visit to his son's prep school to note that each of the larger classrooms was equipped with the latest in audio-visual education aids. In the government, the Office of Education is producing many new films; there are many good films for free rental through federal agencies.

The trend can be examined in two branches of education outside the classroom, for education does not stop with the final graduation or degree. In business, movies have been slow to reach the po- tentialities ,they"possess for good public relatioris'Or sales. General Mills, as an old user of films, has watched the "phenomenal success of training films developed by the Armed Forces during World War II." Its newest film is a new departure in public relations, a first venture into the audiovisual education field, and very likely the first film made especially by home economists for home economics students. In addition to the movie, stills from it are put into a film strip to give classes cues for discussion. A complete literature kit giving every available aid to the teacher is distributed. The kit includes materials to test what the audience has learned from the film. This company has followed the Armed Forces pattern to a T.

Finally, international relations experts have taken their cue from the success of the wartime indoctrination film, as many articles and editorials in recent home and business magazines make clear. A recent Life article on Arthur Rank's British challenge to Hollywood's near-monopoly contains these sentences: "Furthermore, motion pictures probably are the greatest single stimulant to the export sales of a nation's products. This is especially true of consumers' goods—automobiles, washing machines, household gadgets, and so on. By reflecting the customs and tastes of a people (no matter how incorrectly) they become cumulatively the most effective of all ambassadors 'Trade used to follow the flag,' say the British. 'Now it follows the film.'" The same point of view has been made independently by several writers. Because this is true, the international division of RCA is busy with orders for film-recording units (used successfully by the Allied governments during the war) and audio-visual projectors. Australia, Brazil, New Zealand and the Netherlands have all announced plans to use the movie as a powerful diplomatic and trade weaponthe modern way of distributing knowledge and information.

Interesting as these new trends beyond our campus are, both in general and as attracting an increasing number of Dartmouth graduates in a business way, our job remains in the classroom. It doesn't follow that techniques that work outside the classroom will also work inside it, but in this case the experiments have been made and the proof is at hand. Properly used, classroom movies can be and are a valuable and increasingly vital aid to learning.

PROFESSOR OF PSYCHOLOGY

THE AUTHOR SELECTS A SHORT FILM for a Psychology class. Professor Allen's department has some 30 reels of movies, mostly at an elementary level, and a large library of slides, as do many other departments in the College. Slide films are now being developed as a new medium.

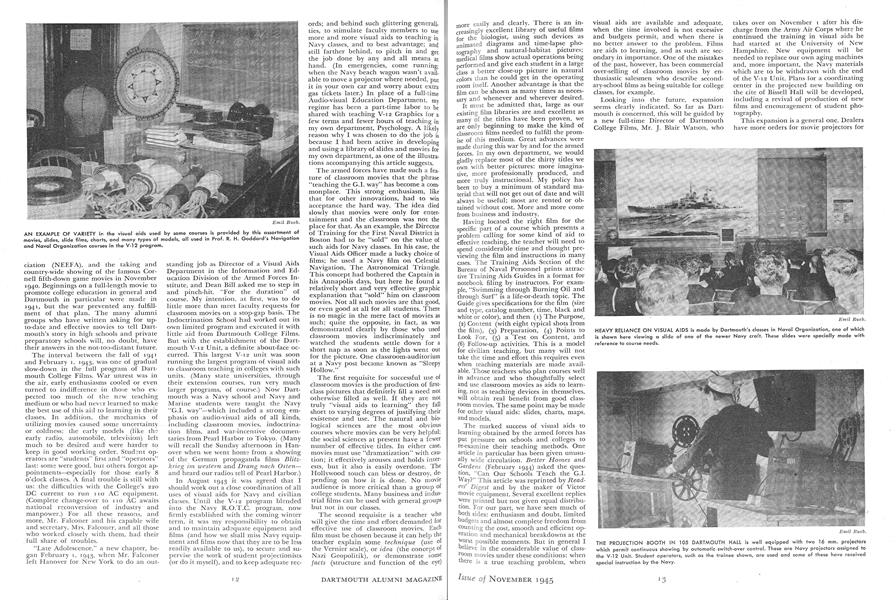

AN EXAMPLE OF VARIETY in the visual aids used by some courses is provided by this assortment of movies, slides, slide films, charts, and many types of models, all used in Prof. R. H. Goddard's Navigation and Naval Organization courses in the V-12 program.

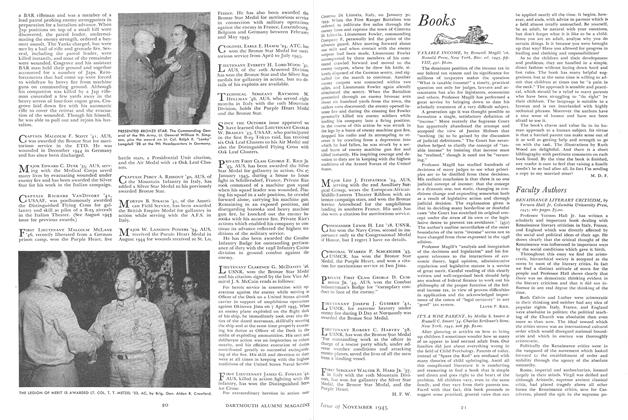

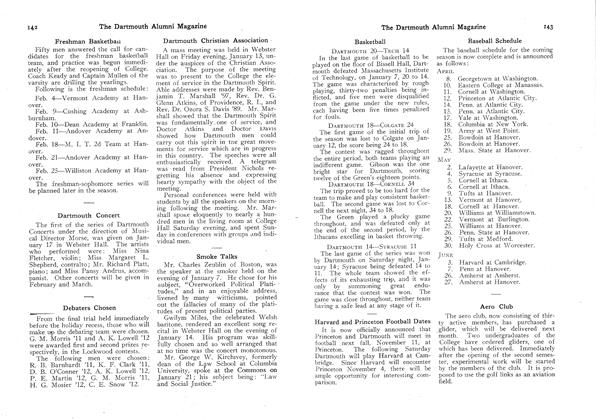

HEAVY RELIANCE ON VISUAL AIDS is made by Dartmouth's classes in Naval Organization, one of which is shown here viewing a slide of one of the newer Navy craft. These slides were specially made with reference to course needs.

THE PROJECTION BOOTH IN 105 DARTMOUTH HALL is well equipped with two 16 mm. projectors which permit continuous showing by automatic switch-over control. These are Navy projectors assigned to the V-12 Unit. Student operators, such as the trainee shown, are used and some of these have received special instruction by the Navy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1945 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTUN BRITTAN JR. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

November 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

November 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1945 -

Article

ArticleWhat a Change!

November 1945 By P. S. M.

Article

-

Article

ArticleBaseball Schedule

February, 1911 -

Article

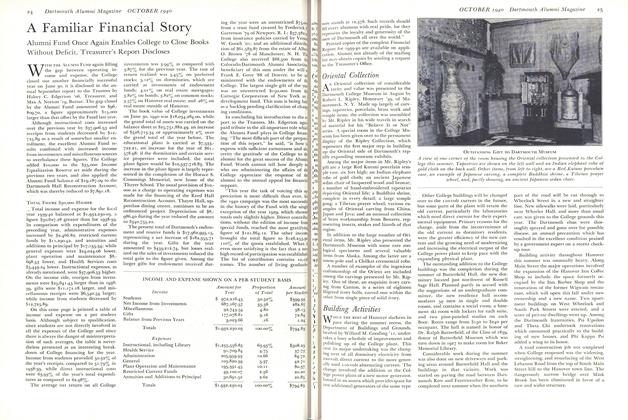

ArticleINCOME AND EXPENSE SHOWN ON A PER STUDENT BASIS

October 1940 -

Article

ArticleJustice from Dartmouth

December 1988 -

Article

ArticleAmerica's First Ski Tow

APRIL 1994 -

Article

ArticleSKATING TEACHER JOINS STAFF

February 1940 By Edward Fritz '40 -

Article

ArticlePhiladelphia

JUNE 1967 By PETER M. STERN '63