ARBITRATION IN ANY CASE where experts find themselves in serious disagreement is proverbially difficult, and in no case more so than in that which affects the problem presented by what is usually called "liberal" education. That problem involves the ideal apportionment of scientific and non-scientific elements in the intellectual dietary to be set before the student. There is general agreement, it seems, that apportionment is in order. That is to say, those who champion the cause of the sciences and those who champion the cause of the so-called "humanities" go so far as to admit that each has a valid claim to consideration and that neither can be regarded as wholly excluding the other. The difficulty arises when it is a question of the measure of importance ot be allotted to each.

Even a rather extreme devotee of the "humanities" will, in these days, stop short of the claim that the humanities alone provide an exclusive mental regimen. The sweeping dictum of the late John Jay Chapman, that proper nourishment for the human soul is to be found alone in "the Bible and the Greek classics," would probably get short shrift today, even in the house of its friends. It is coming to be admitted that any graven image typifying Liberal Education would have to be Janus-headed, facing both forward and backward, like one intent on what man has done, as well as on what man has yet to do. But there is bound to be debate on the details, sometimes with a tinge of acrimony born of a wonted factional partisanship which it would seem desirable to abandon. We all have tolerant words to say for the other side—but how much do we mean by them?

It seems difficult to deny that complete freedom on the part of the neophyte to choose what he happens to relish in the collegiate menu is undesirable; but it is equally difficult to set metes and bounds to freedom or to be dogmatic concerning the best way to insure the intake of sufficient mental vitamins, since one man's meat remains another man's poison, and since some allergies are genuine, alike in the physical and the spiritual world. This particular writer feels that some restriction, rather than a still greater freedom of choice, would be desirable; but in this matter there are at least two schools of thought; and laymen are pretty sure to differ from professional educators therein, whatever be true within the charmed circle of the latter.

In any event there is bound to be divergence of opinions as to just what things it is essential every liberally educated man should know; and until those things are determined it is obvious folly to attempt making schedules of what subjects, humanitarian or other, shall be required. One is speaking, remember, only of the things that give students "background"not of things leading toward professional life—but things essential to the wellbeing of every well educated man, be he doctor, lawyer, or merchant-prince, author, musician, or electrical engineer. May not one distinguish between the things peculiar to specific professions, and those which relate to men as men—or, as the late Philip Hale used to say, "man as a social and political beast?"

No wise saying gains much in wisdom merely because it was first said in Latin, but it happens that one appropriate to this discussion was uttered in that tongue: "I am a man, and hold that nothing which affects mankind is alien to me." Alas, few are so gifted as to take all learning for their province. What we are after is an agreed list of the "musts"; of the things no one can afford to be without—what someone has called "the quintessential sine quanon." It may be a chase after the Will-o'- the-Wisp; but with what zeal do men prosecute that chase! All we seem to agree on at present is that the ideal "required" curriculum won't be all science, or all humanitarian. All right! Where do we go from here?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleVISUAL AIDS TO LEARNING

November 1945 By C. N. ALLEN '24, -

Class Notes

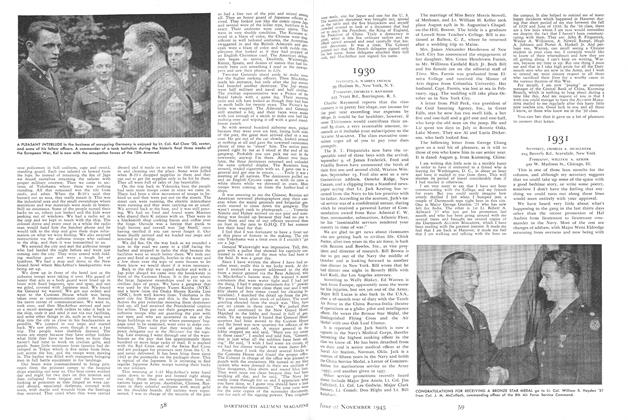

Class Notes1929

November 1945 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTUN BRITTAN JR. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

November 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

November 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1945

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleThe Overmastering Need

February 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWorship of the Plan

April 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleGradus ad Quod?

February 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWho Calls the Tune?

April 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleFraternities Hereafter

February 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleMusic and Drama

April 1946 By P. S. M.

Article

-

Article

ArticleGone Today, Here Tomorrow

MAY 1978 -

Article

ArticleClub Calendar

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's First Skiers

May 1947 By Horace G. Pender '97, Weld A. Rollins '97, Hermon Holt Jr. '97 -

Article

ArticleDisciplined Games

January 1976 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleHOW JUDAH DANA, DARTMOUTH 1795, WON HIS HANOVER BRIDE

May 1918 By James A. Spalding, '66¹ -

Article

ArticleThayer School

June 1942 By William P. Kimball '29