President Hopkins States Views in Letter to "Times"

PRESIDENT HOPKINS' views on the desirability of universal military training were stated at some length in a letter to the editor of The New York Times in the issue of Sunday, May 6. The following day his statement was read into the Congressional Record, and widespread interest has been aroused by his strong support of military training. Because of the special interest which Dartmouth alumni will have in this full statement of President Hopkins' position, the ALUMNI MAGAZINE herewith reprints his letter in full:

lii consideration of the debate about the desirability for universal military training, too little attention, it seems to me, is given to the essential fairness of the proposal. Whatever the temporary inconvenience or minor sacrifice in the individual case or the necessity for readjustments upon us collectively, it is far more just that some responsibility for the maintenance of free institutions should be laid successively upon each generation for a brief time than that periodically every few decades the tragedy of war should be imposed for half decades or more upon generations contemporaneous with the respective emergencies.

I do not assume that permanent immunity from war can be made completely certain whatever we do. On the basis, however, of some continuing contacts with sentiment abroad through the years since World War I, I am fully persuaded that a well-devised and intelligently established system of universal military training would be in very large degree insurance against the frequency of war and might be more. I cannot think of any proposition that I should not consider imperative that decreased in slightest degree the hazard of war or even increased the span of time between one war and another.

I want a system of universal military training established in the United States because I believe it would make wars less likely. For the second time in little over two decades I watch day by day the mounting list of Dartmouth's dead. Other colleges and universities have like lists. And beypnd these are the thousands upon thousands of attractive lads of other associations and other backgrounds who all together were to constitute the warp and the woof of the pattern of our citizenship in years to come,—a pattern that now can never be what it might have been. It is not an experience that can be borne except in grief to receive the daily items announcing the deaths of boys over whom one has watched with affection and with keen anticipation of what they might have become or to realize the sorrow imposed upon their suffering families. It does not make for poise and calm and philosophical rationalization about the minutiae of daily living. Rather it makes for anguished query whether as a people we must always be subjected to the cost of our lack of realism. This lack has been so great that our naivete has cried out for the barbaric peoples of the earth to cultivate their envies of the wealth and the well-being which have been ours and to plan to seize these or at least to deny them to us.

It has been estimated by military authorities that Nazism could have been stopped at the time of the invasion of the Rhineland at a cost of a few hundred casualties at the most, and at the boundaries of Austria at a cost of a few thousand, had organization and will existed among peace-loving nations to have undertaken resistance then. I once ajsked a distinguished American in the Government whether any resistance on those occasions had been considered. "With what?" he replied. "Neither the United States nor England had trained men, materiel or convictions in those years."

It isn't reassuring to reflect what would be pur situation at the present time if any one of numberless things hadn't occurred, particularly England's dogged and exhausting defense while we slowly came to understanding of what the War was all about; or Russia's entry into the War and her valor in it while we slowly got under way. If we in opulence, inertia and selfrighteousness withhold from preparedness for a possible World War 111, we will invite it. And when it strikes with robot bombs, rocket guns and all that developing scientific research can afford an aggressor in years to come, its resemblance to Pearl Harbor will be analogous to that of a modern B-sg air attack as compared with a movie representation of an Indian attack on a frontier settlement.

But someone says, "Possibly so, but what does that prove about universal military training?" "Everything," in my belief. The circumstances of modern life demand elimination of any time lag as a factor in preparedness. The measure of our defense will be the extent not only of our provision for war but also of our readiness for it for long time to come, except for agreement more binding than anything now in sight.

Public sentiment in Europe as I saw it in the two decades following World War I offered many warnings of on-rushing tragedy. Increasing year by year subsequent to our refusal to enter the League of Nations the insistent belief cumulatively developed among the peoples of the Continent that the United States not only would not take any responsibility to support the peace-loving nations of the world but that on the contrary we were so confident of our immunity from attack that we believed we could safely accept the hazard of doing nothing to defend ourselves against possible aggression. In 1934-35 this was particularly so not only among the Germans and the Italians but also among the French. German university men, students and graduates, stated frankly that the Reich was about ready to take over supremacy in Europe and Italian Fascist officers boasted of what they were going to do in making the Mediterranean Sea their own exclusive lake. Again and again I asked whether there was no concern at all among them about public sentiment in England and America. With no single exception that I can remember was the question answered with anything except amused tolerance among those most friendly or derisive comments among others as to the lack of public spirit and of virility in the soft and effete democracies.

In Rome a Fascist officer in Mussolini's personal guard told me of voluminous reports of Fascist agents in the United States that the churches were all so antimilitaristic that we would not be able to undertake any preparation for war unless we were attacked, when it would have come too late for us to accomplish anything. At Taormina young German officers, some educated in this country and others in England, assured me that their Secret Service reports showed that schools and colleges in these countries, were almost completely dominated by pacifist sentiment, whether in faculties or student bodies. All cited the Oxford Oath against war as representative of the sentiment of youth in both countries. It was futile to explain to them the casual irresponsibility with which in democracies our student bodies were prone to issue dogmatic statements on questions such as this. It would have been a greater waste of time and breath to have told them where these selfsame boys would be found when they should eventually come to realistic understanding of the truth.

The most revealing experience of all to me as to what our attitude was doing to jeopardize our own safety eventually as well as to invite disaster to the rest of the world came in France early in 1935. In conversation with the spokesman of a brilliant group of young physicians, himself a distinguished veteran of World War I and neither rightist nor leftist in sympathies but inclined to lean toward the Popular Front, he said nevertheless that common sentiment held that France had been deserted and betrayed since Versailles by both England and America, that she was defenseless against Germany, and that many believed there was no hope for her except in an alliance with Russia or Germany. Personally he was inclined to think Germany the safer choice. He read me letters to the same effect from other veterans of World War I written to him in great concern as to the trend of public thought. Many of the letters bespoke not only distrust of but antagonism towards the United States and England. "The United States," he said, "if in the League could with England have assured peace in Europe and given France safety. We were led to rely on that. As it is, our only hope of security is not to offend Germany." Then sadly came the conclusion of the whole affair as far as he and his friends were concerned. "Public sentiment being what it is, if someone on a white horse were to ride through the gates of Paris tomorrow, the world would be astonished at the following that would turn out to accept leadership from him." He begged me to make these facts clear to my friends at home.

Again I seem to hear the comment, "But what does all this have to do with universal military training?" Again I answer, "Everything." Any disposition in America towards preparedness would have given Germany and Italy pause and France reassurance. I would at this point, listening to the arguments of those who oppose universal military training, freely grant, as I have stated before, that wars may still be a possibility after a post-war organization for the maintenance of peace is set up. Words will not necessarily preclude war. An organization in which the great powers sit together in continuous session to smooth out differences and to try to maintain peace will be a long step towards eliminating some of the hazards that lead to war. As such it is imperative but it can never in itself be a complete barrier. All available additional insurance against war must be taken out likewise and such insurance could be a population which had been wholly conditioned in body, mind and spirit to the idea that it could have just as much freedom as it was willing to defend, and no more. No such conditioning has been existent for years in the American home, church or school. This, it may be assumed, has something to do with the fact that we have had to fight two wars in less than three decades. There is Scriptural basis for the argument that under certain conditions lives can be saved only by willingness to lose them; somewhat in analogy, frequently ideals can be saved only by willingness to forego them. This is the answer to be made, it seems to me, to those who argue that because San Francisco is designed to lead the mind of the world toward peace, we should forego any organization internally that would make force available to us to protect ourselves against war if it should threaten.

Regarding the arguments of those who say that universal military training will jeopardize the efforts toward setting up a peace organization, let us not ignore the fact that the idealists have had their day that the League of Nations, the Disarmament Conference, and other such movements were all patterned on the premise that the world had reached a sufficient stage of civilization so that in the future wars would be outlawed. Subsequent events have proved how false that assumption was. Therefore, until such time as the whole world has been educated to the belief and is ready to accept the ideal of enduring peace, it is going to be the responsibility of the peace-loving nations to maintain the peace even by utilization of amply equipped force, if necessary.

People ask me as a college officer if universal training would not disorganize college procedures. The answer of course is "yes." However, the problems of reorganizing life in the college, the home or the community do not interest me in slightest degree beside the possibility that a system of universal military training might save our youth from suffering and dying in war a quarter of a century from now. Neither does the plaint that a year of public service of this sort will do violence to scientific research or industrial development or labor organization or budding artistic genius.' None of these impulses are as easily blighted as such complaints would imply to be the fact.

The proposal for universal military training is a proposition purely and simply to enhance the military security of our people. Its alternative is a huge standing army for years to come. Protection in one way or another must be given against the necessity of becoming involved in wars engendered by those who may in the future believe, as has been believed twice in our time, that our unpreparedness made it safe to violate every principle im which we believe. Moreover, the proposal to my mind is valueless except as it envisages military training exclusively. Valuable byproducts doubtless would accrue to the individual and to society from establishment of the proposition but military security for the American people in the enhanced possibility of escaping future wars must be the one all-inclusive purpose of such a project. Any considerable attention to any other purpose than meeting military necessity would render the plan wasteful and futile.

Finally, for those who fear the effect of the proposal upon the spirit of democracy, the plan seems; to me to embody the very essence of democracy in imposing alike upon all equal responsibility for the maintenance of the democratic state and the freedoms they derive from this. It is possible of course to summon up a host of hypothetical assumptions that this, that or the other thing might work out badly. Any project new in a given circumstance is subject to such attack. Rationalization in regard to untried conditions can always evoke a multitude of reasons why they should not be undertaken. There unquestionably would be some inconvenience and some disappointments involved in the readjustments of such a plan. I grant it. But my eye turns to the pages of fine print in The Times by my chair,— the headings are "Dead," "Wounded," "Missing." After this I am not interested in the inconveniences to be met by institutions or individuals. I do not care how great the problems of readjustments may be in the fields of learning, labor or managment. I am not even concerned over possible changes in our form of government if freedom be safeguarded or whether our taxes be greater or less. The only thing that seems to me of the slightest consequence in the world is that boys like these shall not again have to walk this Gethsemane,—that these pages of fine print shall never again have to be published. A nation-wide preparedness to such extent as universal military training would provide might make such possibilities into probabilities. I pray it may be tried.

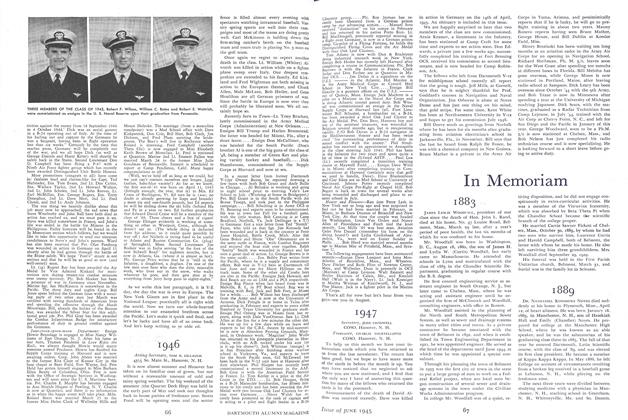

WHEN NOT ON ITS GOOD BEHAVIOR the Connecticut River can create great havoc with spring or fall floods. This picture shows the high water at Ledyard Bridge in the last serious flood in March 1936.

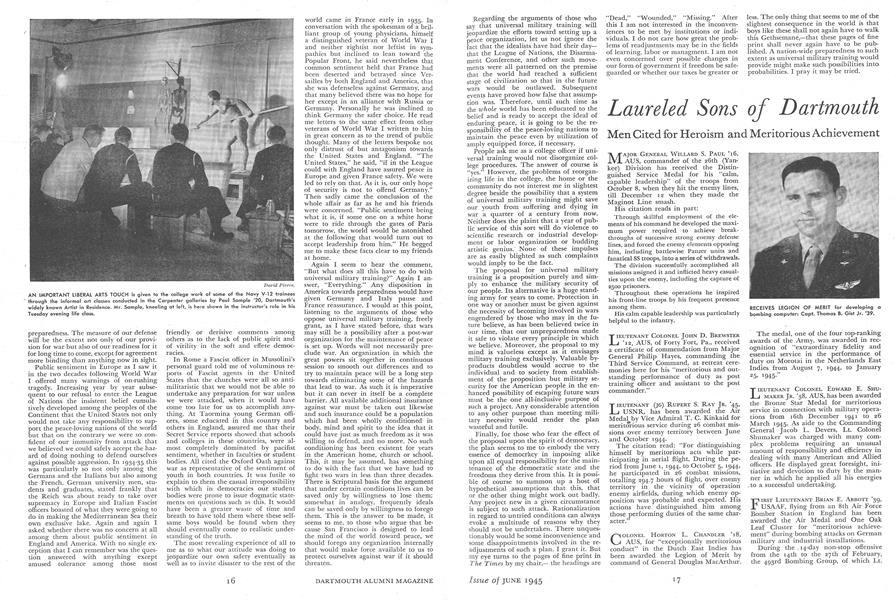

AN IMPORTANT LIBERAL ARTS TOUCH is given to the college work of some of the Navy V-12 trainees through the informal art classes conducted in the Carpenter galleries by Paul Sample '2O, Dartmouth's widely known Artist in Residence. Mr. Sample, kneeling at left, is here shown in the instructor's role in his Tuesday evening life class.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S RIVER

June 1945 By Alice Pollard -

Article

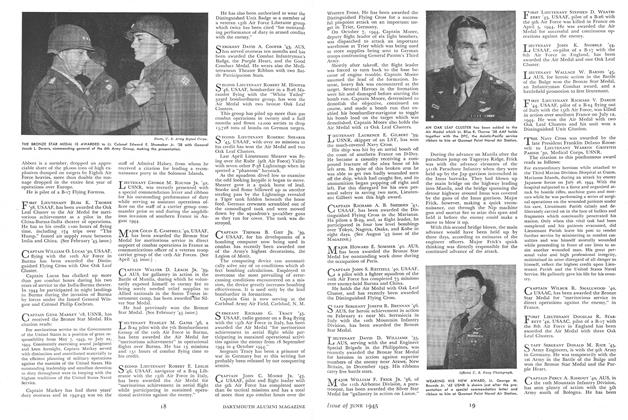

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

June 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

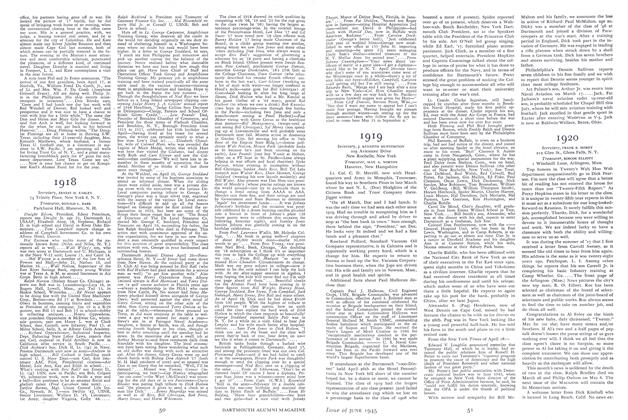

Class Notes1918

June 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

June 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1908

June 1945 By LAURENCE SYMMES, WILLIAM D KNIGHT, ARTHUR BARNES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

June 1945 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

-

Article

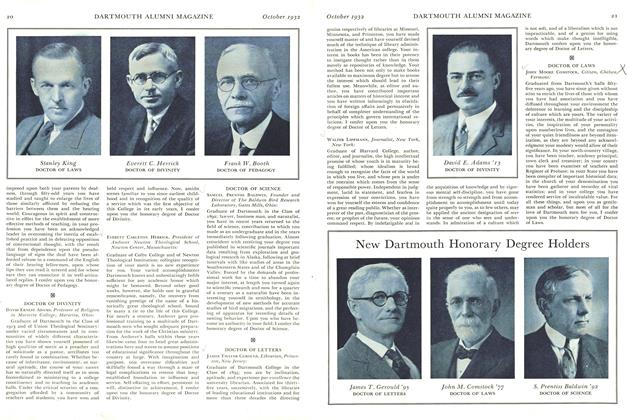

ArticleNew Dartmouth Honorary Degree Holders

October 1932 -

Article

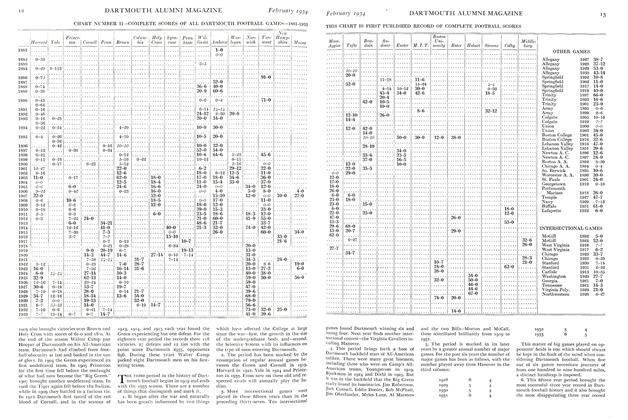

ArticleCHART NUMBER II—COMPLETE SCORES OF ALL DARTMOUTH FOOTBALL GAMES—1881-1933

February 1934 -

Article

ArticleProfessor of Religion

February 1944 -

Article

ArticleA Wall Hoo Wah!

February 1951 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleTHE CONCEPT OF HEROISM

MAY 1991 By James O. Freedman