A Profile of S/Sgt. Walter Bernstein '40 of "Yank"

IT WAS AT ONE of those amphibious landings in the Pacific which are heralded in the stateside headlines as meeting with slight opposition. A fragment of the "slight opposition" had blown up in the face of a Yank correspondent, combing him with shrapnel and leaving his face looking like something hung in a slaughter house for chilling. In fact, the Yank correspondent was not badly hurt; in appearance, as he sat on the beach awaiting evacuation, he was a bad casualty.

An infantryman passing by, looked down and asked with quick sympathy, "What outfit ya with, Bud?"

"Yank," mumbled the bloody-faced correspondent.

"Yank? What a soft racket you got," was the rejoinder of the no-longer sympathetic dogface as he moved along.

S/Sgt. Walter Bernstein '40, who tells the story, agrees that being a correspondent for Yank is a soft racket when you stack it alongside the job of the combat infantryman, although he feels that the doggie could have picked a happier moment to comment on the cushiness of a berth with the Army Weekly.

Sergeant Bernstein is in a pretty good position to judge the cushiness of a berth with Yank, inasmuch as he is one of the Army Weekly's better-known correspondents. He can also speak with some au- thority on the life of a combat infantryman, since his basic training on entering the AUS was with the infantry and since he has done most of his writing for Yank while living the dangerous and monotonous life of a grimy dogface.

While an undergraduate at Dartmouth, Walter Bernstein could never have been pictured as speaking with the slightest authority about the life of an infantryman, particularly a combat infantryman who was fighting for his country. In Hanover, Walter gravitated to the left and found his major interests represented by such organizations as The Junto and the American Students Union. With considerable enthusiasm, he engaged in the ASU program which included, among other things, the organization of the so-called nation-wide annual' "peace strike," in which college students remained away from classes for one day to register their unalterable opposition to war and to demonstrate their determination never to fight for the United States in any "im- perialistic" war—by implied definition, any war.

In pursuit of his ideals in college, Bernstein displayed a lack of humor oddly at variance with the personal wit which found its expression in the pages of jacko-lantern and which was also on irregular display in The New Yorker. Despite his facility in writing light material, when it became a question of "social significance," Walter was frequently the author of totally humorless articles which lacked the grace even to laugh at their own pretensions.

An article, typical of Bernstein at his humorless worst, appeared in The Dartmouth during his sophomore year and for a spell was a campus cause célèbre. At the time Bernstein was the daily's movie reviewer, and in his review of LostHorizon, he criticised the film violently for its "escapist doctrine." Most of the outraged undergraduates who sprang to the defense of the picture were as blind as Bernstein to the fact that criticising a single film for its "escapist doctrine" was like criticising one particular Madison Avenue bus because it didn't run down Fifth Avenue. The route of Madison Avenue buses should, perhaps, lie along Fifth Avenue; but it is not a legitimate cause for complaint against one particular bus that it follows the established route. Similarly, it may be true that the movie industry in the Fall of 1937 (as in the Summer of 1945) exhibited an escapist philosophy; it was, however, ridiculous to level the charge against any one cinema product in a review column devoted to evaluating pictures largely in terms of other pictures. But, then interested in pummeling escapist philosophy, Bernstein failed completely to take a real look (and laugh to match) at his own review.

There are few who would care to quarrel with the basic sentiments Bernstein expressed when he wrote: "It seems to us that if a- society is rotten the thing to do is get out and fix it, hot retreat to a little Shangri-La and watch it go to pot." Many, however, would challenge the concept that all entertainment must perform a "social" function, that escapist entertainment is evil per se. And many others would agree that to judge a single picture on its percentage of escapism is arrant nonsense when the entire industry is shot through with that philosophy.

In the 'midst of the furor ensuing over the review in The Dartmouth, Bernstein was solemnly hailed into the editor's office and told that his services as the paper's movie reviewer were no longer required. Walter admits that the discharge left him very unhappy for quite a while. However, in the end it may have been a good thing for him, inasmuch as it channeled more of his writing energies into jacko where he polished the technic that The NewYorker soon recognized as first cousin to its own. By the end of his junior year, Bernstein had sold his initial story, HouseParty, to Harold Ross's literary grab-bag.

Following his graduation in 1940, Walter Bernstein set out to conquer the world by doing a little of everything. He acted as play-doctor for an ailing drama which was looking for Broadway production. His ministrations may have been successful; but the patient, All In Favor, expired after seven rapid performances on Broadway. He wrote a few pieces for The NewYorker-, he paid a visit to the wilds of Hollywood, half hoping his art would be prostituted by the greedy moguls of cinemaland. The movie kings weren't buying any Bernsteins that month, and so he returned to his native habitat of Brooklyn, where on February 24, 1941, he found that Draft Board 179 had requisitioned his services for a year with the Army of the United States. On December 7 of that year, an event occurred which extended his year of service indefinitely.

At first a member of the Eighth Infantry Regiment of the Fourth Motorized Infantry Division, Bernstein got his basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia. In a matter of months, despite the widespread GI belief that in the Army no square peg ever meets a square hole, Bernstein; found himself doing public relations for the Infantry School at Benning, and in 1942 when Irving Berlin's This Is theArmy headed for New York, Sgt. Walter Bernstein came along in a capacity which he says was "vaguely that of an enlisted press agent." However vague the job was when it started, it grew even more vague when opening night found one of the soldier chorus-members missing. The opening scene of This Is the Army featured a production number by the chorus which was designed to be timed and sung with precision; and the opening night audience could have been excused for thinking that the show was ineptly staged because right smack in the middle of the chorus was a man who was up when he should have been down, down when he should have been up, who hummed the songs instead of singing, and generally added nothing to the finesse of the socko opening. The soldier displaying two left feet to the premiere audience was Bernstein, drafted a second time by the Army, this time on a few minutes' notice to serve as a chorus-boy. "They said I had to get in theifi," Walter explains, "but they didn't say I had to be good."

Walter's fumbling performance on opening night may not have been caused entirely by his lack of familiarity with the chorus routine; he may well still have been seeing colonels on his court-martial board. Just prior to the opening of ThisIs the Army, Bernstein had written an article on the soldier show for The NewYorker. The editors liked it; they bought it; and as a routine matter, they consulted 90 Church Street, New York, for clearance on the piece. The New Yorker's presses were waiting open jawed, but no word came from go Church. Harold Ross, determined and splenetic New Yorker editor, called downtown, gave his name and asked to speak with the colonel. The colonel, Ross was informed, was too busy. "Well tell him," stormed the editor, "that unless I hear from him by 5 o'clock today, I am going to run Sergeant Bernstein's article."

A few moments later, Ross's telephone buzzed. It was the colonel. His message was brief and pointed. "Mr. Ross," he purred, "I think it wise to inform you that half an hour after The New Yorker, appears with Sergeant Bernstein's article, the sergeant will be court-martialed."

Ross blurted an approximation of "the hell you say," hung up, turned to the jittery Bernstein and said, "Don't worry, Walter. He can't do that to us."

Walter knew one thing Ross didn't know; he knew the colonel could do it to half of them, and that he was the half. However, trying to calm an infuriated Ross was like trying to bat down a B-29 with a gut-strung tennis racket, so Walter regretfully prepared to experience the joylessness of Fort Leavenworth, only to be saved at the last moment when the colonel's permission for publication was forthcoming.

Before the New York run of This Is theArmy was finished, the press agentry and incidental writing of Bernstein had attracted the attention of Yank's editors, and after the usual amount of hauling and tugging, enough Army red tape was cut to free him from his job with the show and attach him to the staff of the magazine. Then began the real experiences of Sergeant Bernstein, experiences which carried him around the world in pursuit of feature material for Yank and which sent him to such spots as the Middle East and the Persian Gulf Command, Libya and Algiers, Sicily, Italy, and the Anzio breakthrough, which certainly deserves a billing all its own. His overseas activity was topped off by a month and a half with the Partisans in Yugoslavia, during which time Bernstein became the first American to interview Marshal Tito, leader of the Partisans.

If Bernstein weren't exactly a close cousin of the dogface when he joined the staff of Yank (and there is a question as to whether a few months' infantry training and a subsequent erratic public relations career makes a man kin to the lonely dogface), he soon became a doggie by association if in no other way. Today, it is cheap to say that a man writes like Ernie Pyle; it is so cheap and so easy that a writer who mentions any enlisted man by name immediately becomes a "second Pyle." Bernstein is no "second Pyle," and yet there is much of the Pyle feeling in many of his pieces. Pyle was, if anything, less restrained, less afraid to allow his emotions some freedom, less (if you please) New Yorkerish than Bernstein. Nevertheless, they had more than a little in common. Of the "free" correspondents, Pyle was virtually the only one who made a fetish of finding out how the doggies lived and died by actually living with them. Bernstein, like all Yank correspondents, always lived the life of the troops he was to write about, and hence both Bernstein and Pyle began with the same material, collected in similar foxholes, under similar artillery barrages and in similar muck and dirt and death. Pyle created masterpieces of war reporting; Bernstein created articles which, if lesser masterpieces, are no less simple and no less honest than Pyle's. The jacket blurb of Bernstein's recently published book, Keep Your Head Down, says in part,

"Bernstein is a skilled and sensitive reporter who presents his story in an enviably simple and graphic manner " There never has been a blurb more truthful, nay, more restrained, than that. Bernstein began with a Leica-like eye, and as he went along, it became more and more selective until he was photographing nothing but the essentials, small and large, of any incident.

As an aid to the understanding of Bernstein's ideas and ideals and of his progress intellectually, Keep Your HeadDown has great and natural limitations. In the first place, the Army does not encourage its enlisted personnel to express opinions; in the second place, the semi-stiff upper lip method of expressing emotion and thought which is employed by The New Yorker is definitely restrictive. Bernstein was writing for both, with the result that his thoughts are obliquely presented and usually demand much cooperation from the reader.

Certainly it is an oblique commentary on the Army Orientation program when Bernstein, in telling of his experiences among the Partisans, writes:

"But the hardest thing to accept about these two, and about the younger Partisans in general, was not their youth but their normality. They were all completely healthy, because they knew why they were killing and what it meant to them. There were practically no cases of war neurosis in Tito's army, and the main reason is that they have a good idea why they are fighting and believe in this idea."

One thing is certain from even cursory inspection of Bernstein's writing: he hasn't lost his ability to see laughable situa- tions and to write laughably of them even when there may be an underlying grimness. In an article on paratroopers, for example, he says, "The Army doesn't believe in asking a man to jump out of a moving airplane unless the man wants wholeheartedly, or at least half-heartedly, to jump." That is pretty good capsule coverage of a situation in which all the men are supposed to be free-will volunteers, yet where pressures of one sort and another make the volunteering something less than a complete exercise of free will. Sgt. Walter Bernstein is back in the United States now, attached to the New York office of Yank. He considers himself a pretty lucky soldier because he has been able to follow his chosen line of work while in the Army, and also because he had his head down at the crucial moments throughout his months overseas. With 98 points, he has enough for a discharge and a side of beef to boot; but the men in the brass hats haven't decided whether Yank is so essential that none of its personnel can be released under the Army point system.* If they make up their minds affirmatively however, they will turn Bernstein loose on a civilian world which knows him better now than when he went into the Army and which has a taste for the prose in which his reports have been couched. Reconversion will be no problem.

Walter's advance as a writer while in the Army is easily noted. In terms of TheNew Yorkers style, he has become adept at reaching the emotional essentials of a situation with a few simple words. He has pushed that style to its logical conclusion and, as a craftsman, can advance no further in the form. As a thinker, Bernstein is still left of center, with the distinct advantage of being bound to no group and being required to follow no party line. The degree of his mental maturity, while considerable, is hard to measure accurately. He has not outgrown the need to justify past positions which have since become untenable. For example, in explaining his participation in peace strikes as late as five years ago, he says: "It still seems to me perfectly logical to be against one kind of war five years ago and for another kind today. The world changes; and I was never a pacifist, but an antimilitarist." The historical record, of course, shows that Hitler was as obvious an enemy in 1936, "37, or '38 as he was in 1941. The peace strikes in which Bernstein engaged were strikes against all wars and not, as he says, "militaristic" wqrs, whatever that qualification means in a democracy. It is, perhaps, unfair to Bernstein to consider his rationalizing a sign of lack of maturity, inasmuch as most people, including many generally considered fully mature, are constantly guilty of rationalizing. Apparently it is a cliche of our civilization to worship a personal infallibility in which it actually has no belief. On the positive side, Bernstein has matured intellectually to the point where he recognizes that there can be fundamental, irreconcilable disagreement between men of good will, with perfect honesty on both sides. That is possibly the greatest of tributes to his development, inasmuch as it is a level which the majority never uses.

You'll hear of Walter Bernstein many times in the future; but it is impossible to say just what you will hear. He will face a personal crisis on his release from the Army. He may stay in The NewYorker groove and grow gradually famous without progressing a step; he can easily turn to slicker publications and grow more quickly famous while retrogressing; he may go forward in every sense and become a writer of literature. His name may be attached to plays, movies, essays, novels, or short stories; but it will be attached to many things you will read in the next twenty years. Time and Bernstein alone will determine whether his name will be on anything you read in forty years.

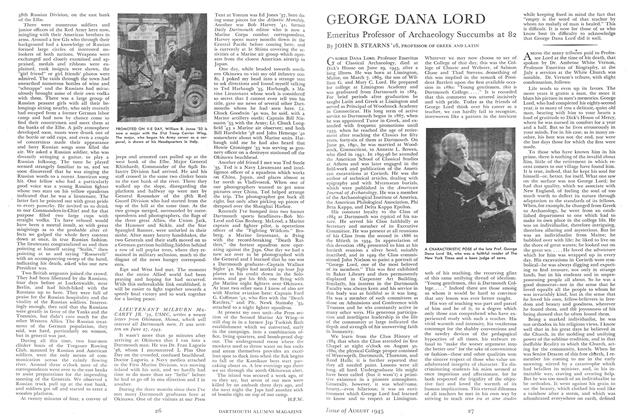

STAFF SERGEANT WALTER BERNSTEIN '40

The MAGAZINE presents this month the first of a series of alumni "profiles" by Lynn Callaway '38 of Hartsdale, N. Y. Others will appear from time to time in future issues. Mr. Callaway, who was sports editor of The Dartmouth, has done some free lance writing since he left college and more recently has been engaged in industrial public relations. For the past three years he has edited 1938's prize newsletter, ThePace Setter.

* Editor's Note: Sergeant Bernstein reported to a separation center on July 11 in preparation for his discharge from the Army.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEDICAL SCHOOL

August 1945 By DR. JOHN F. GILE '16 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

August 1945 -

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

August 1945 By H.F.W. -

Article

ArticleMedical School

August 1945 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

August 1945 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

August 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR

LYNN CALLAWAY '38

Article

-

Article

ArticleSTATISTICS OF DARTMOUTH PREPARATORY SCHOOLS

January, 1912 -

Article

ArticleThayer School Contributors

December 1957 By Estabrook, F.D. '41 -

Article

ArticleCalifornia Founder

March 1940 By Harris Elwood Stark -

Article

ArticleDumpster Diver

Mar/Apr 2006 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleThe Door to Dartmouth

February 1956 By R.L.A. -

Article

ArticleThayer School

December 1944 By William P. Kimball '29