Radio at Dartmouth, Less Than Decade Old, Grows Into Potent Campus Force

WE NOW PRESENT for the first time ... These are the words you would hear again and again if the 30 watts of WDBS pushed into your loudspeaker. These are the words that more and more people in the Hanover community have been hearing in the past two years. For by all odds the most distinguishing characteristic of WDBS, the Dartmouth College station, is the ambition of its allstudent personnel—the drive to do new things in production, advertising and engineering.

One doesn't have to delve far into the past to find a time when such was not the case, for WDBS is still in its first decade. WDBS, then DBS, made its first official broadcast to the College on September 23, 1941, and the station still uses some of the microphones employed in that inaugural broadcast. As I looked over Joseph Hirschberg's History of Radio atDartmouth, written in 1942, I was struck by the great difficulties involved in starting a college radio station. Not that the administration wasn't cooperative, but the technical difficulties the student founders had to fight against seem almost insurmountable to those of us who were pre- sented a working technical system at the outset. Several times, the station's top men were playing a furtive game of hideand-seek with the Federal Communications Commission.

On December 7, 1941, DBS remained on the air all night to bring to the newshungry college word about the disaster at Pearl Harbor. Although they didn't realize it at the time, the announcers were spelling out the end for the college station, at least for a while. The end didn't come until the spring of 1943, when people were interested in more important things than radio and when the blue of the Navy was adding a more somber color to the Dartmouth scene. About three years later, in March of 1946, DBS was again open for business, but it was not until last year, under the excellent management of Bud Popke '49, and with the enthusiastic members of the first real postwar class—l9so— the directorate positions, that the college station started to become an actual force on the campus. This year, the trend upward has continued and, for the members of the new directorate, the opportunities seem to be bounded only by their capabilities.

Today, WDBS is a carrier-current station operating on the college power lines. It is a member of COSO and subsidized to the extent of about $1000 annually. This presents a challenge to the staff, since all the money they can derive from advertising over the amount submitted in the budget request will go into new equipment. Consequently, all year long, the production men are trying to put out better programs, the technical people are trying to make a better signal available to a larger audience, and the advertising department is trying to sell those shows in larger and larger quantities. Last year, it happened that the station found itself with a surplus and, since surplus money can't be carried over from one year to the next because of a most peculiar bookkeeping arrangement, the station returned to COSO about $400 of the subsidy rather than purchase equipment ill-advisedly.

The station has a faculty adviser, Professor Almon Ives, of the Department of Speech, but he wisely permits the students to make most of the decisions and waits for them to come to him with problems, at which time he helps in any way he can. The top men in the station's organizational scheme cannot receive salaries under the present set-up—a situation which it is hoped can be changed some day. Even a check for $50 at the end of the year would be some sort of recognition of accomplishment for the station manager.

Whenever I've explained the organization of WDBS to businessmen (most of whom know nothing about college radio, even those men in commercial radio), they are always aghast when I point out that the top executives change every year. Yet it is this very change that makes possible the ambition mentioned earlier. Each station manager and his staff are seeking to make their terms of office more outstanding in every respect than that of their predecessors. What about any long-range planning, you will say. Well, it would seem that, idealistic as it sounds, a sort of affection for the organization takes hold of its members if they have worked hard for several years, and the students in authority take great pains to see that the station can progress, even after they have left Dartmouth behind them. In that spirit, Bob Sisk '50 and I, as co-managers, recently drew up an equipment plan for the next five years so that we may buy our equipment on something more than a hitor-miss basis. This plan can be completely scrapped, of course, by next year's directorate, but at least the program has been charted.

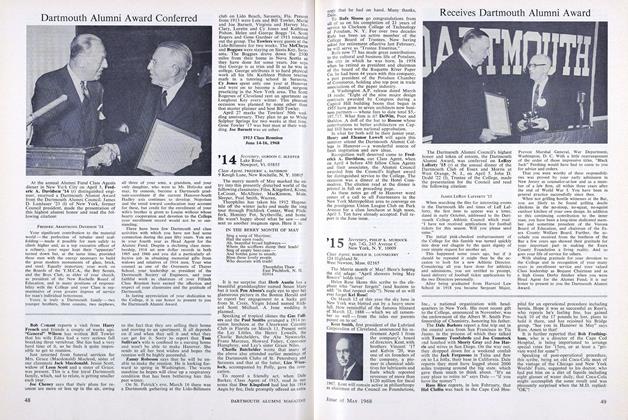

The announcer above is Bill Terry '51 ofScarsdale, N. Y., Production Director ofWDBS for the coming year.

In the past few years, we've found that approximately 120 freshmen come out for heeling competition annually. Usually about half of them are kept for the first year, the rest dropping out for lack of interest or lack of talent in the phase of broadcasting they wanted to undertake. Most of them want to announce, naturally enough, but it's hard to find even three potential announcers out of the group. The voices of college freshmen are subject to all sorts of weird squeaks and croaks, necessitating a stay of indeterminate length in script-writing until their voices stop fluctuating from tenor to bass. After the 60 heelers finish their first year, they start figuring out where they are going in the station's scheme of things. If they see no bright future in store for them, they usually drop out, which fits in with the plans of the directorate since a staff of that size couldn't be handled.

Very, very few men who come out for WDBS are interested in making radio a career; a few more, like myself, find out through working at the station that this is what they want to do in life. The great majority of them will become businessmen like their fathers, but since radio, even at Dartmouth, is more of a business than an art, the experience they gain can be invaluable. It probably won't help them in getting a job, but the things they learn in working with people should show to good advantage once they start working. Take the station manager's job for instance: the task of maintaining a functioning radio station which broadcasts 10 hours a day to the highly critical college audience is not particularly easy in itself, but to do it with staff members who receive no salaries and whose first duty is to their studies gives one some idea of the experience that can be gained. Among other things, one learns that almost all freshmen are idealists who look for the perfection that is never there, who must be nursed through the first few months of disillusion at finding that even seniors can and do make mistakes. If they can be guided through these first critical months and still retain their spirit and drive, one finds that he is working with a group whose enthusiasm to learn cannot be equalled anywhere else in the radio field.

Not all the people who come into the station are new to the entertainment world. John Gambling '51, new station manager, had appeared many times on his father's program over WOR before he saw the Dartmouth campus. Louis deRochemont '52, one of the program directors, bears a name famous in the motion-picture industry. Then too, some of the men do go into radio after graduation. NBC has taken several men who worked on WDBS; Bud Popke '49, last year's station manager, is now with WTOR in Torrington, Conn., and there are others.

The programming problem of WDBS is somewhat unique, since the audience is sharply divided between the Dartmouth students and the Hanover townspeople. The first loyalty must be with the students since this is a college station, but the townspeople cannot be forgotten since they too trade at the stores which sponsor the programs, and town and gown have always been one community in Hanover. A majority of the students would probably prefer to hear uninterrupted music punctuated only by play-by-play sports coverage, but to do that would be to lose sight of another objective—that of providing training in radio for members of the student staff. Consequently a compromise must be reached; not all the programs can be listened to while studying, yet there is plenty of music.

Naturally the sponsors want to have some idea of how many people are listening to the programs on which they are spending money, so the station must conduct polls. These also help in programming as the production director learns what programs are being avoided by the listeners; he tries to smooth out the rough spots in the unpopular shows or, perhaps, scraps them in favor of something else. Polling is somewhat of a problem since there are no telephones in the dormitory rooms, so the heelers must make the rounds of the rooms selected in a scientific sample. Usually, they try to poll at least six hours of a broadcasting week, sometimes more, using two men in hour shifts.

A POLLSTER AT WORK

Here is a scene that is repeated over and over again in every dormitory. There is a knock at the door. A muffled "Come in." The WDBS heeler steps into the room, equipped with his list of questions and blanks to be filled in. The room is occupied by two students who have been interrupted from their books. There is not a sound in the room. The heeler duly asks his first question, "Are you listening to your radio?"

The occupants look amazed. "Do you hear anything?" one asks.

"I guess you're not listening, huh," says the heeler as he backs out of the door.

"Thanks anyway."

The students look annoyed momentarily as the heeler, outside in the hall, fills in the appropriate blank. He clatters off to his next assigned room which may be over in another dormitory. End of scene.

From the reports that this heeler and others like him bring back, the business staff can tell Mr. Piane how his Co-op show from 10:30 to 11:00 is being received. As a further check, he will watch the sales of the particular product he is pushing at the moment. Frequently the Hanover merchants will advertise different products in The Dartmouth and on WDBS to judge their relative effectiveness. It is, of course, quite difficult to judge the tangible results of any kind of advertising. Last year, one of the Hanover ice-cream stores started a vigorous campaign over WDBS, advertising ice-cream cones in the middle of January. When the response was not overwhelming, it was taken as a condemnation of radio advertising and the store has not advertised since.

Suppose we follow a program through from its formulative stage to the present, thereby getting an idea of the functions of the various departments of WDBS. The one I've chosen is the one with which I'm most familiar—the Student-Faculty Quiz.

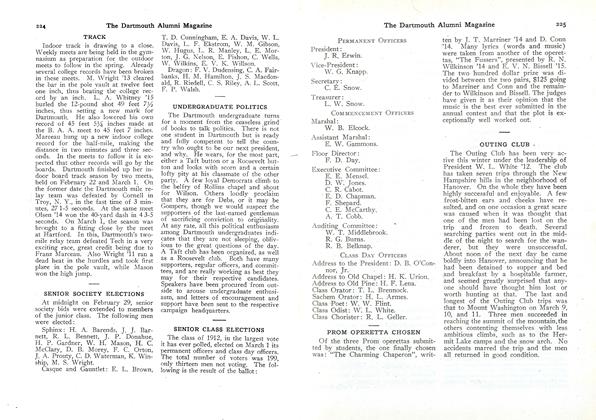

It started as a not-too-original idea to a quiz show with students and faculty members participating on a non-competitive basis. It would be nothing new in the entertainment world—lnformation Please having made its appearance some years before—and its success would depend on the cooperation of the professors and the skill with which it was handled,. First, a time must be allotted. This was to be a show on which a lot of effort was to be expended, so a good time was given it by the Production Director—10:30 on Tuesday night, since it has found that the time most Dartmouth students like to listen to their radio is from 10:30 to 11:30.

Two of the more intellectual members of the production staff were assigned to the show—Steve Kandel '48 and Walt Barney '51. Before the response to questions started coming from the listeners, they had to make up the questions as well as get the participants. Luckily, it turned out that a great many professors were delighted to appear on the program, so that was not the problem it was expected to be. Usually a moderator and producer would have to be assigned, but since I had decided to do both myself, that was not necessary in this case.

The program started out in October as a 15-minute affair, but then it became evident that a half-hour was needed, since the experts took a few precious minutes of radio time to get warmed up. For the first few weeks, all elements of the program had to be tested: the mikes had to be constantly shifted to find the right balance, different types of questions and participants had to be tried out, and I was discovering that the little cards I had with the answers printed on them were a puny defense against the mass of erudition with which I was bombarded. All this testing was being done while we were actually on the air, but the program was not pushing off any worthy show, and we had faith that we could eventually make the Quiz an entertaining and informative half-hour.

The first break came when the Chesterfield campus representative approached us with the idea of sending a carton of Chesterfields to any person whose question stumped our board of experts. This provided some incentive for the listeners to send in questions and took some strain off the two production men. Shortly afterwards, one of the heelers in the business department, Kent Robinson '53, was able to sell the show for 13 weeks to Rogers Garage in Hanover.

Today the show has a good listenerrating (not as good as some music shows for the simple reason that it is hard to study by) and it elicits quite a bit of favorable comment. There are two semipermanent members of the board—Professor John C. Adams of the Department of History and Dan Featherston '50, Editorial Chairman of The Dartmouth. There are still a few kinks—the technical quality is a bit shoddy because the studio is inadequately sound-proofed, and it is hard to get good questions from the ones sent in—but we are working on these problems. This is just one of dozens of programs that have their particular problems and their special virtues.

Now in its sixth year of actual broadcasting, the station is proud of many accomplishments. It is proud of its ambitious program schedule, including many "remotes" (broadcasts originating beyond the studios). Piano shows from the lounge of the Hanover Inn, concerts from Webster Hall, sporting events from Alumni Gym, Davis Rink and the athletic fields, "away" contests from other colleges gain experience and prestige for the station. It is proud that its "console," or control board, was designed and built entirely by the students. It is proud of the opportunity it gives to high school youngsters on Friday afternoons to get some taste of this relatively new medium. Most of all, perhaps, it is proud of the spirit of its personnel which makes them work long hours, often without the credit they deserve. Several times, technical men have worked all night to get some new piece of equipment installed for the next morning's broadcast.

The organization feels a sense of responsibilty somewhat more keenly than most radio stations. Hanover is fairly remote from most commercial stations and, in many cases, WDBS is the only signal which can be received with any degree of clarity. While this is a good thing as far as the advertising department is concerned, it means that the programs presented must be those that the majority of the audience like to hear. There can, for instance, be no repetition of the Menfrom Mars program of several years ago which made many listeners believe that the United States was being attacked.

Also, being a college station, WDBS feels that it should present programs that add something to liberal education. Most concerts and lectures are carried, along with debates on controversial subjects, news headlines every hour, and the best in recorded classical music. College projects like the Chest Fund and Carnival are supported to the best of the station's ability.

Fortunately, WDBS and The Dartmouth have been on the best of terms thus far, a situation which doesn't exist on some campuses. While the advertising men compete hotly for, say, James Campion's advertising, the newspaper and the radio station have cooperated splendidly at every opportunity.

What WDBS needs now is increased national advertising. To that end, the Ivy Network was formed almost two years ago. The network is a purely business arrangement consisting of the college stations at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Pennsylvania, and Dartmouth. By offering the advertising agencies a market of five "class audiences," roughly equivalent, it is hoped that Ivy presents a market which the agencies will find is worth bothering with. Each station produces its own programs so that the expense of telephone lines is avoided. The idea is gaining momentum and every few months a new account is added, but although national advertising is increasing, it is not doing so to the extent its potentialities to sponsors would seem to indicate.

SPACE AT A PREMIUM

Another crying need is for more room. At times, every WDBS room in Robinson Hall (and there are six) overflows with workers. During these periods of feverish activity, perhaps some of the directorate may want to talk privately. This means a retreat to the newsroom, where the UP teletype clatters in the background, to a dormitory room, or even to a Robinson Hall washroom hastily appropriated for a conference. Latecomers to the regular Tuesday station meeting may be obliged to perch on top of the piano or, worse still, stand outside in the hall. WDBS has grown phenomenally in its short life.

Several months ago, the last member of the station who could actually remember the first telephoned record request left school (incidentally, to go into the NBC Executive Training Program). At the present time, WDBS receives over 200 requests a week from an audience including students who have to pay a nickel to telephone.

In short, WDBS has come of age, but because it is made up of students who actually run the station and because there are always new opportunities to be explored, the most significant characteristic in the organization, as I have said before, is the ambition of its personnel. The spirit is a refreshing one with which to work, and through it WDBS can continue to be an ever-increasing source of entertainment and experience in this fascinating medium to members of the Dartmouth community.

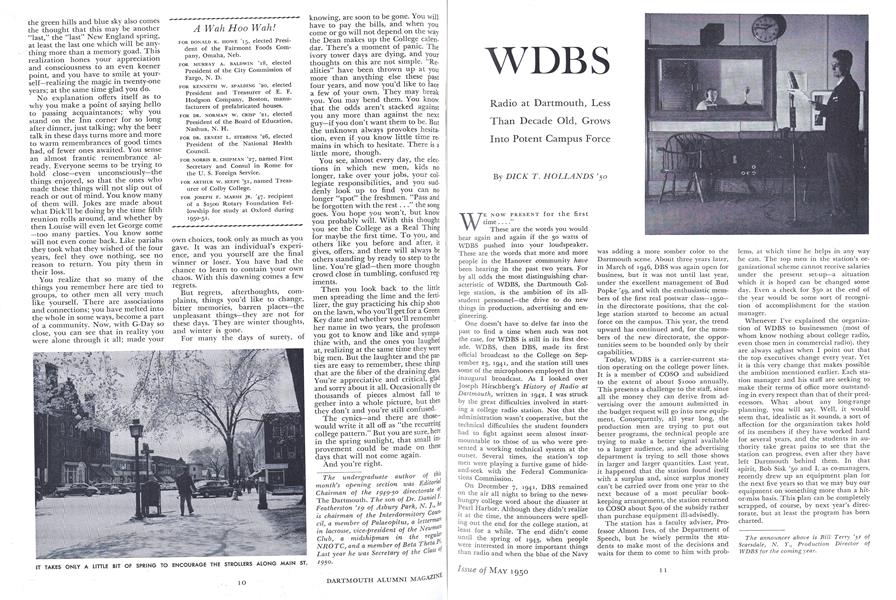

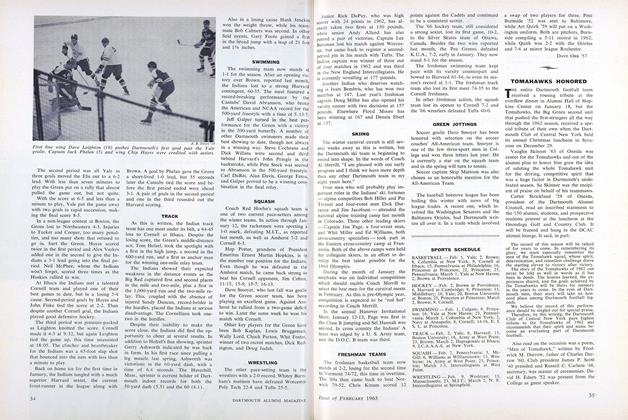

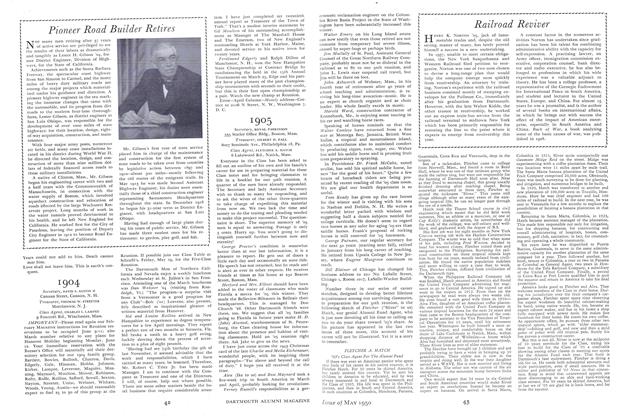

BASEBALL BROADCAST AT MEMORIAL FIELD: Some of WDBS's best work is done with play-by-play broadcasts of Big Green sports events, directed this year by Bob Sisk '5O (second from left), station co-manager from Hartford, Conn. At left is Bill Brooks '5l of Upper Montclair, N. J., who will be in charge of special events during the coming year.

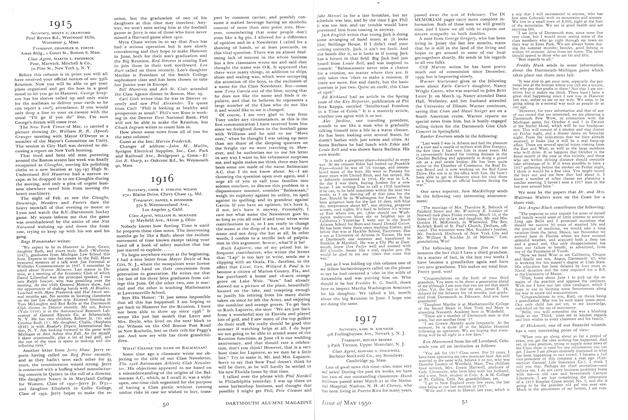

TWO OF THE MOST POPULAR WDBS FEATURES: "Let's Make Music," on the air Thursdays at 10:30 P.M., and "Student-Faculty Quiz," on Tuesdays at the same time, rate high with listeners. The music-makers (left) feature Vocalist Nancy Warnock, wife of William Warnock '48, of Belmont, Mass.; Bob Pilsbury '48, pianist, of Newtonville, Mass.; and John Klein '52, announcer, of Cleveland Heights, Ohio. The Quiz Program moves fast, with such pundits as Prof. John C. Adams of the History Department and Edward F. Grier of the English Department in the verbal arena. At right, Dick Hollands '50 of Hornell, N. Y., author of this WDBS article and son of William G. Hollands '27, serves as moderator. The student side is represented here by Dan Featherston '50, of Deal, N. J., author of this month's opening editorial page, and Mrs. Fred Federlein ('5O).

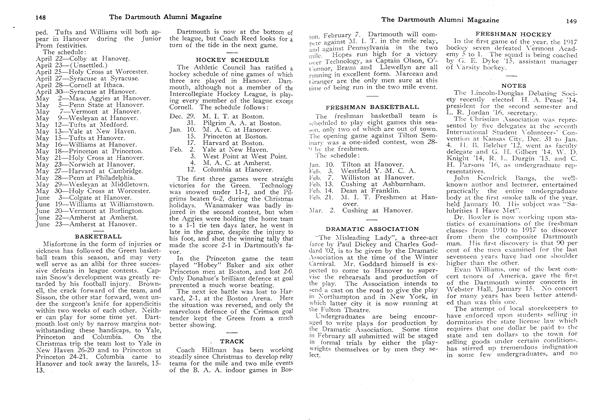

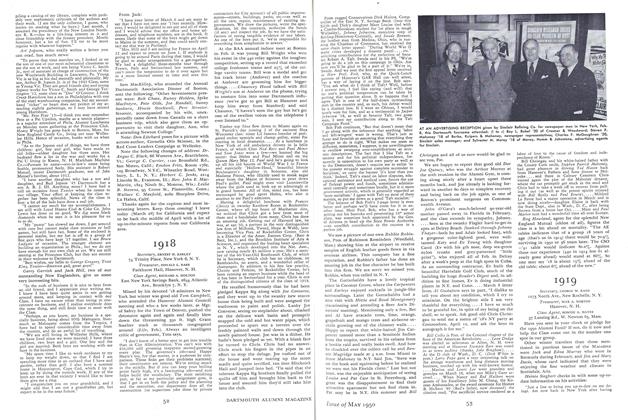

THE BUSINESS SIDE of radio at Dartmouth was directed this year by Jim Gaylord '5O of Springfield, Mass. (standing, right), WDBS Business Manager. Bob Oliver '50 of Torrington, Conn, (leftjwas Assistant Business Manager. Seated is Ted Bailey '51 of Cedar Grove, N. J., Business Manager for 1950-51.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

May 1950 By KARL W. KOENICER, DONALD BROOKS, HOWARD A. STOCKWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, LEON H. YOUNG JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

May 1950 By ROYAL PARKINSON, GILBERT H. FALL, FLETCHER A. HATCH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

May 1950 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Article

ArticleWhat's Ahead for 1950?

May 1950