Published by The Tabard,Dartmouth College, 1951. 37 pp. $.60.

Tabard 1951 is a collection of the best examples of recent student writing at Dartmouth submitted in a contest sponsored last spring by The Tabard, undergraduate writing club, which begins its second year of existence this fall. The four short stories and two poems that make up the volume indicate that recent student writing at Dartmouth is doing very well indeed.

For the writing in Tabard 1951 is firm and competent writing, quite capable of standing on its own merits, needing no" fatherly pat from any reviewer inclined to be indulgent because of college associations. True, all four of the stories deal more or less centrally with child characters—in one instance with teenagers. This might seem to reflect the national preoccupation with children that is becoming increasingly noticeable in the American professional short story and that led the editor of one of the large popular magazines to announce recently that for some time to come his magazine would be interested only in stories about adults.

But to undergraduate writers this stricture hardly applies. It is a truism that the young writer does better to concern himself with areas of physical and emotional experience not too far removed from his own, and while this truism may be brilliantly violated at times, it still remains the best guide for his mind and typewriter.

Furthermore the stories in Tabard 1951 are sufficiently varied in background and handling to avoid any impression of monotony or repetitiousness.

In "The Warmth of August" Mr. Blakemore deals simply and with a minimum of sentimentality with two of the most emotional effervescent ingredients at any writer's disposal —a neglected child and a dying dog. Mr. McMahon in "The Street" uses racial antagonisms, none the less destructive because released only on a traditional occasion once a year, to shatter his Jewish boy's trust in life. The characters in Mr. Meyers' story "The Price of The Passionate Virgin" are more off the beaten track, less familiar in type, than those in the other stories. The fact that some of the characters need a little further filling in for perfect clarity hardly lessens the interest in the story. "Summer's End," Mr. Zuckerman's story of a small boy charged with an errand by his dying grandmother, achieves an unusual degree of concentration and intensity, and, toward the end, a mounting suspense that gives a moment or two of genuine excitement.

Of the two poems in the volume Mr. Wheatley's seems to this reviewer at least the more completely realized. "Amo" by Mr. Robinson proceeds through a series of well wrought pictures to a somewhat familiar conclusion. "Railroad Warning" by Mr. Wheatley, on the other hand, takes a fresh and personal experience and broadens it, easily and inevitably, into universal significance.

We look forward to Tabard 1952.

A review of "The Idea and Practice ofGeneral Education" appears on Page 25.

For a listing of recent articles by alumni andfaculty, see Page 95.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

October 1951 By C.E.W. -

Article

ArticleThe Moral Supports or Education

October 1951 By C.E.W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

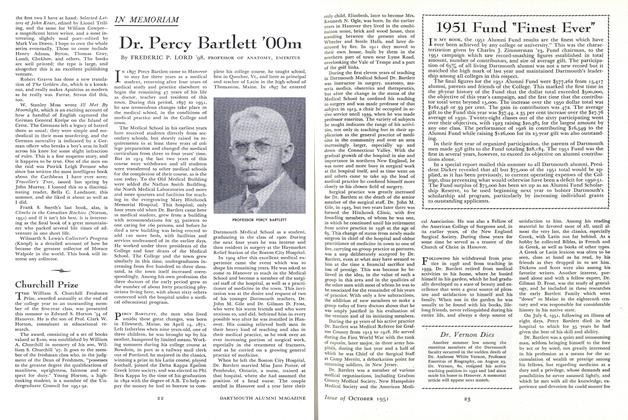

ArticleDr. Percy Bartlett '00m

October 1951 By FREDERIC P. LORD '98 -

Class Notes

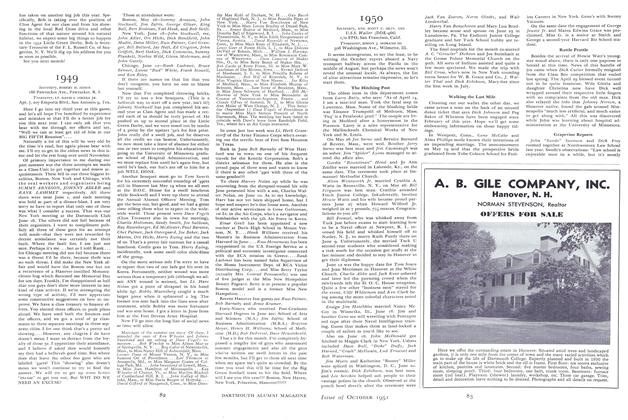

Class Notes1950

October 1951 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, USN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Article

ArticleAssociated School News

October 1951 By Karl Hill

Kenneth A. Robinson

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

DECEMBER 1926 By Kenneth A. Robinson -

Books

BooksWALT WHITMAN IN ENGLAND

October 1934 By Kenneth A. Robinson -

Books

BooksTHE FIRST CENTURY OF AMERICAN LITERATURE

October 1935 By Kenneth A. Robinson -

Books

BooksBACK WHERE I CAME FROM

April 1939 By Kenneth A. Robinson -

Books

BooksHOW TO BECOME PRESIDENT

November 1940 By Kenneth A. Robinson -

Books

BooksWALT WHITMAN RECONSIDERED.

December 1955 By KENNETH A. ROBINSON

Books

-

Books

BooksThe Fight for Peace: an Aggressive Campaign for American Churches

-

Books

BooksShelflife

Mar/Apr 2006 -

Books

BooksSTEEPLE BUSH

July 1947 By Francis Lane Childs '06 -

Books

BooksFor Robert Frost

MARCH 1963 By J. TERRY CORBET '62 -

Books

BooksA PICTORIAL HISTORY OF THE GREAT COMEDIANS.

JANUARY 1971 By PETER WERNER '68 -

Books

BooksSeeing Tilley Plain

OCT. 1977 By R.H.R.