THE "CUSSEDEST" MAN CONGRESS EVER HAD

MANY colleges can legitimately boast to having produced the most eloquent, the most brilliant, the most patriotic or the most beloved figure in American Congressional history. Dartmouth, however, can make the unique claim to having graduated the bitterest, the cussedest, the most venomous, the most obstinate - and perhaps the most power-ful—man who ever sat in the National Legislature.

He was Thaddeus Stevens of the Class of 1814.

In the tumultuous Reconstruction days after Lincoln's moderate and steadying hand was snatched from the helm, Thad Stevens more than any other person browbeat the Congress, overrode the Executive and fashioned the vindictive, crushing and questionable policy which the North for many years maintained toward the defeated South.

And yet there was a cantankerous nobility in the man. He was a born troublemaker, a hater and a bully. He was cynical, overbearing and cruel. His relations with his quadroon housekeeper were an open scandal. His political operations were not always unconnected with personal gain. Yet he had a passionate love of freedom and a fierce devotion to the ideal of the equality of man before his Creator that cancelled out his faults.

Charles Summer in his eulogy of Stevens called him "the most remarkable character identified with the House," excepting only John Quincy Adams, and in his peroration in the full rhetoric of the time, he concluded:

"It is as a defender of human rights that Thaddeus Stevens deserves our homage. Here he is supreme. On other questions he erred. On the finances, his errors were signal. But history will forget these and other failings, as it bends with reverence before those exalted labors by which humanity has been advanced. . . . Politician, calculator, time-server stand aside! A hero-statesman passes to his reward."

It often happens that the bitterness and cynicism of mature years can be traced back to physical infirmity and an unhappy childhood. Such was the case with Thaddeus Stevens. He was born lame and sickly, on April 4, 1792, in the harsh frontier simplicity of Danville, Vermont. His father was a dissipated and improvident cobbler who died of a bayonet wound received in the War of 181 a. His mother bore the burden of raising the family and struggled to give the club-footed boy an education far above the average for their locale and status in life.

He entered Dartmouth in 1811 as a sophomore and, except for one term at the University of Vermont, he studied in Hanover until his graduation. Among his professors were John Wheelock, son of Eleazar, Zephaniah Moore who taught Latin and Greek, and Ebenezer Adams who taught Mathematics and Natural Philosophy.

Those were stirring days in Hanover since the College was the scene of the tug-of-war between the Trustees and the Legislature which culminated in the Dartmouth College Case.

After his graduation, Stevens went back to Vermont, but within a year left New England permanently to make his home at York, Gettysburg and later Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He taught school for a while but soon gravitated to the bar and, as a natural adjunct, entered politics. His law practice was characteristic of the litigious frontier controversy of the times and he was highly successful. It was in the brawling, tempestuous politics of Pennsylvania, however, that he found the atmosphere that he loved and for the remainder of his life he devoted himself to the gentle science with an assiduity which few but bachelors like himself can afford.

Stevens gained his first wide notoriety as a promoter of the Anti-Masonic party and he rode that horse to the limit of its endurance and beyond. In reality he was primarily using and fostering issues which would count against the hated Democrats and, with others, during the extended demise of the Whigs, he was pressing toward the creation of the Republican Party. His real fight and the lasting contribution of his Pennsylvania legislative days, however, came with the passage of the law which set up a system of free common schools for the State of Pennsylvania. It was his proudest achievement.

He could drop from the sublime to the earthy with facility. Always one with an eye out for the main chance, Stevens devoted much of his legislative time to the creation of a railroad which followed such a tortuous path in order to serve his iron works that it was christened "The Tapeworm."

WITH his election to the House of Representatives in 1849, Stevens entered upon the service that was to continue, with an interruption of six years, until his death and which remains one of the most remarkable in our history. The embers which grew into the conflagration of the Civil War were then bursting into flame and Stevens characteristically and decisively took his place in the camp of the extreme Northerners. He announced his violent opposition to slavery, and particularly to its extension into the new territories, with an eloquence and a vehemence which enraged the Southern members and brought his name and his speeches into every newspaper in the country. At times he seems to have placed himself in physical danger. Here is an eye-witness report of a scene during one of his speeches: "The leading members from the slaveholding states were gathered in front of his desk. As he portrayed the degradation and the crime of slavery, in such a manner as he only could portray them, scowls settled on their brows, contempt curled their lips and oaths could be distinctly heard hissing through their teeth — I felt alarmed for him, but he proceeded unembarrassed by interruptions and apparently unconscious of the mutterings of the storm. He was as cool as if addressing a jury in his county courthouse."

It was in the course of one of these speeches that Stevens scornfully countered the complacent and comfortable argument of the Southerners that the slave was "free from care, contented, sleek and fat." He suggested that instead of the proposed legislative compromise between slaveholding and free territories there be another personal compromise with master and slave changing places "by which the oppressed master may slide into that happy state where he can stretch his sleek limbs on the sunny ground without fear of disarranging his toilet; where he will have no care for tomorrow; another will be bound to find him meat and drink, food and raiment, and provide for the infirmities of old age."

He continued: "Last of all would I reproach the South. I honor her courage and fidelity. Even in a bad, wicked cause, she shows a united front. All her sons are faithful to the cause of human bondage because it is their cause. But the North the poor, timid, mercenary, driveling North - has no such united defenders of her cause although it is the cause of human liberty - She is offered up as a sacrifice to propitiate Southern tyranny — to conciliate Southern treason."

Even his famous fellow alumnus did not escape his wrath. After Webster's famous speech on the Compromise of 1850, Stevens angrily exploded: "As I heard it, I could have cut his damned heart out."

Stevens retired from Congress in 1853 but he continued to work and speak for the anti-slavery cause. Meanwhile he devoted himself successfully to business and the law. Then in 1859 at the age of 66 he ran again for Congress, was elected and returned to the battlefield.

Stevens met the rising storm of rebellion head on. He challenged the South to go to war. He threw the threats of secession back in the faces of the members who made them. He viewed war as an opportunity to free the slaves, to punish the South and to crush its ruling class. Given the uncompromising Southern attitude, he could see no solution but war and he welcomed its leveling effect. With his unshakable predilections, his force and his eloquence, he soon became the leader of the House.

One reporter said: "Thaddeus Stevens was the despotic ruler of the House. No Republican was permitted by 'Old Thad' to oppose his imperious will without receiving a tongue-lashing that terrified others if it did not bring the refractory representative back to party harness. Rising by degrees - until he stood in a most ungraceful attitude, his heavy black hair falling down over his cavernous brows, and his cold little eyes twinkling with anger, he would make some ludicrous remark, and then reaching his full height, he would lecture the offender against the Party discipline, sweeping him with his large, bony right hand, in uncouth gestures, as if he would clutch him and shake him John Randolph . .. was never so ingeniously insulting as was Mr. Stevens toward those whose political actions he controlled."

He bent Congress to his will. He was equipped with a savage, fighting spirit. He scorned the legal quibblers. He hated the degrading major premise of slave-ocracy. He "nerved the Nation to war."

When the frightful, bloody conflict came, Stevens put the full force of his personality behind the Northern effort. He supported Lincoln, but he had no patience with Lincoln's careful balancing between Abolitionists and Border Staters. He pushed through unprecedented tax and appropriation bills. Always, however, he pressed for immediate and unqualified emancipation and ridiculed Lincoln's cautious halfway measures. Finally, the President's policy proved successful, the North held together, the military victories were won, the slaves were declared free and the South surrendered. Then came the tragic murder in Ford's Theatre.

THE stage was now set for Stevens greatest role. As the end of the war approached, he was urging his revolutionary policy of enfranchising the slaves and punishing the slaveholders. He considered the rebel States to be out of the Union and he insisted that they be dealt with as a belligerent nation according to the law of conquest. And, in the words of Claude Bowers, "at the moment the bullet of Booth closed the career of Lincoln, he was less a leader of his Party than Thad Stevens."

If Lincoln had lived, he might have conciliated Stevens and the rest of the Congress and soothed the country and thus he might have carried out the moderate Reconstruction which he appears to have planned. Andrew Johnson, however, was not equal to the task and the conflict between Stevens and his associates and the President, culminating with the President's impeachment, provided the great closing drama of Stevens' life.

The fight centered about the readmission of the Southern States to the Union and the determination of the legal status of the former slaves and slaveholders, but the basic conflict was one between the Executive and the Congress for the control of the national policy toward the South. Stevens, emaciated and weak and verging on death, once again was the vital link joining the national spirit of revenge and the legislative resentment to break Andrew Johnson and wreck his moderate program. Impelled by his hatred of the Southern Bourbons, his genuine love of freedom and equality and his respect for the Constitutional role of Congress, and motivated by a determination to crush Democratic power and strengthen the Republican party, Old Thad gleefully cracked his whip and directed the forces which had been engendered against the hapless President.

The immediate result was the impeachment of Johnson and his acquittal by one vote in the Senate. The long-term effects were carpet-bag rule, the economic strangulation of the South, the destruction of its ruling caste, the Klux IClan, generations of "waving the bloody shirt" and the consolidation of the power of the Republican Party.

For good or ill, Thad Stevens had done his work and done it with a vindictiveness, a relentlessness and a show of power not elsewhere exceeded in our Congressional history. Three months after the trial of Johnson, Stevens, worn out by his exertions, attended by his quadroon mistress and two colored Sisters of Charity, died in Washington, D. C. Baptized at his death by a colored Catholic sister, his burial service at Lancaster, Pennsylvania was read by a Lutheran clergyman and the sermon was preached by an Episcopalian minister. He refused to be buried in the public cemeteries of Lancaster and his grave is marked by this epitaph of his own composition:

"I repose in this quiet and secluded spot, not from any natural preference for solitude, but, finding other cemeteries limited by charter rules as to race, I have chosen this that I might illustrate in my death the principles which I advocated through a long life, Equality of Man before his Creator." .

Says Carl Sandburg: "Scholar, wit, zealot of liberty, part fanatic, part gambler, at his worst a clubfooted wrangler possessed of endless javelins, at his best a majestic and isolated figure wandering in an ancient wilderness thick with thorns,- seeking to bring justice between man and man - who could read the heart of limping, poker-faced old Thaddeus Stevens?"

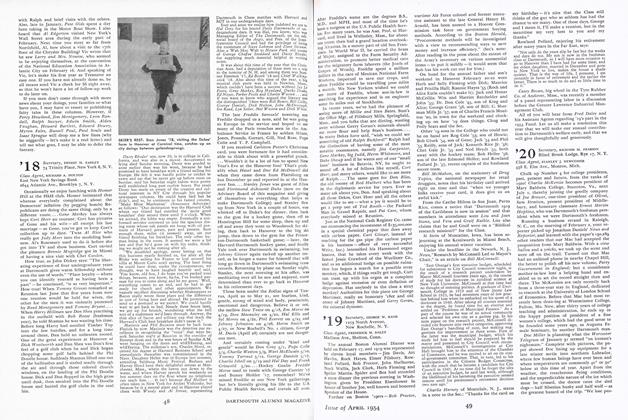

Thaddeus Stevens at the time of the Civil War

Mr. Monagan, an attorney in Waterbury, Conn., has read everything he could about Thaddeus Stevens, a subject that fascinates him. He has had a political career of his own, having served as Democratic mayor of Waterbury for two terms, 1943 to 1947, after being president of the Board of Aldermen. For ten years after graduation he was secretary of the Class of 1933.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAn Introvert at Dartmouth

April 1954 -

Feature

FeatureADMISSIONS—SCHOLARSHIPS—ENROLLMENT

April 1954 By Robert L. Allen '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

April 1954 By REGINALD B. MINER, WILLIAM H. PERRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

April 1954 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, MARVIN L. FREDERICK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

April 1954 By JOHN A. WRIGHT, BEN W. DREW

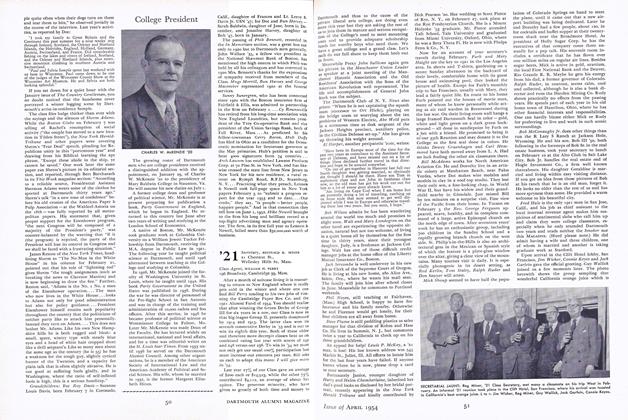

JOHN S. MONAGAN '33

Article

-

Article

ArticleSELECTION OF THE CLASS OF 1926

June, 1922 -

Article

ArticleWho's Who Addition

May 1939 -

Article

ArticleTHAT OLD SWEATSHIRT TRADITION

APRIL 1932 By E. R. Moore '34 -

Article

ArticleTeachers Go To College

February 1943 By Herbert F. West '22. -

Article

ArticleAnd They Say Students Aren't Religious!

January, 1930 By James F. McElroy '31 -

Article

ArticleMusic and Drama

April 1946 By P. S. M.