ISM. By Arthur A. Ekirch Jr. '37. New York:Longmans, Green, 1955. 401 pp. $7.50.

This provocative and well-written book tells the unhappy story of the historic ideal of liberalism in America. The liberalism of which Professor Ekirch writes is basically the faith in individuals and small governmental units rather than in either big business or big government; it emphasized the liberties of the individual and of minorities.

Professor Ekirch traces these ideals throughout the entire course of American history with skill, but also with sorrow, since he obviously likes the concepts of Thomas Jefferson, even though they were compromised in practice, and regrets their passing. Among the villains are Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin Roosevelt, who called themselves liberals and were supported by many people of liberal leanings.

Not only has the history of liberalism been unhappy, according to Professor Ekirch, but the future is even more depressing. The book ends with the summary that "Liberals will at least be able to look back with some satisfaction into the distant past, while they do their best to challenge the fate held out by an increasingly illiberal future.

Quite obviously this thesis will inspire all sorts of arguments. The word "liberalism" itself is pretty slippery, and many Will question its exact meaning in terms of personal freedom; since Professor Ekirch is far from accepting the logical extreme of anarchism, much debatable ground remains. Many will quarrel violently with the insistence that a "liberal" is committed for all time to an unchanging position regardless of time and place. Many will deny the that "liberalism" can be equated with "best,' and that the ideal society is one that eliminates quite sweepingly the actions and controls of large groups. Many will rise in wrath at the objections raised to nationalism. In fact, there are few generalizations made in the book which will not awaken protests by someone.

All these possible criticisms merely emphasize the value of the book. It poses squarely the problem of individualism versus collectivism - of the ideal of opportunity versus that of security. It makes its points effectively and often subtly, for obviously Professor Ekirch has developed greatly as a thinker and writer since his earlier book The Idea of Progress inAmerica, 1815-1860 (1944). The book well deserves its choice by the History Book Club, and one hopes that it will be widely read and inspire the discussion that it deserves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

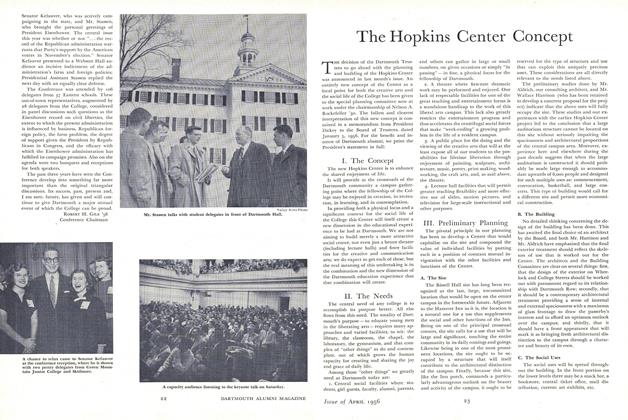

FeatureThe Hopkins Center Concept

April 1956 -

Feature

FeatureTHE MOCK-DUEL MURDER

April 1956 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureELECTION-YEAR CONFERENCE

April 1956 By ROBERT H. GILE '56 -

Feature

FeatureA Tuckerman Tradition

April 1956 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1956 By CHRISTIAN E. BORN, JOHN W. MOXON

ROBERT E. RIEGEL

-

Books

BooksTraining in Citizenship

APRIL, 1927 By Robert E. Riegel -

Books

BooksMAKE EVERYBODY RICH

FEBRUARY 1930 By Robert E. Riegel -

Article

ArticleA College Course for Alumni

January, 1931 By Robert E. Riegel -

Books

BooksJoseph Hawley, Colonial Radical

DECEMBER 1931 By Robert E. Riegel -

Article

ArticleThe New Social Science Program

January 1937 By ROBERT E. RIEGEL -

Books

BooksTHE INDIANS OF TEXAS IN 1830

JUNE 1969 By ROBERT E. RIEGEL

Books

-

Books

BooksNEW VALUES IN MUSIC APPRECIATION

February 1936 By D.E. Cobletgh -

Books

BooksMOUNTAIN CLIMBING GUIDE TO THE GRAND TETONS,

November 1947 By Henry Coulter '43, NATHANIEL L. GOODRICH -

Books

BooksAudubon, the Naturalist, a history of his life and time

April 1918 By L.G. -

Books

BooksTHE EUROPEAN ANCESTRY OF VILLON'S SATIRICAL TESTAMENTS

February 1942 By Leon Verriest -

Books

BooksMARCEL PROUST AND HIS FRENCH

October 1940 By Ramon Guthrie. -

Books

BooksTHE BATTLE AGAINST ISOLATION.

January 1945 By Robert K. Carr '29