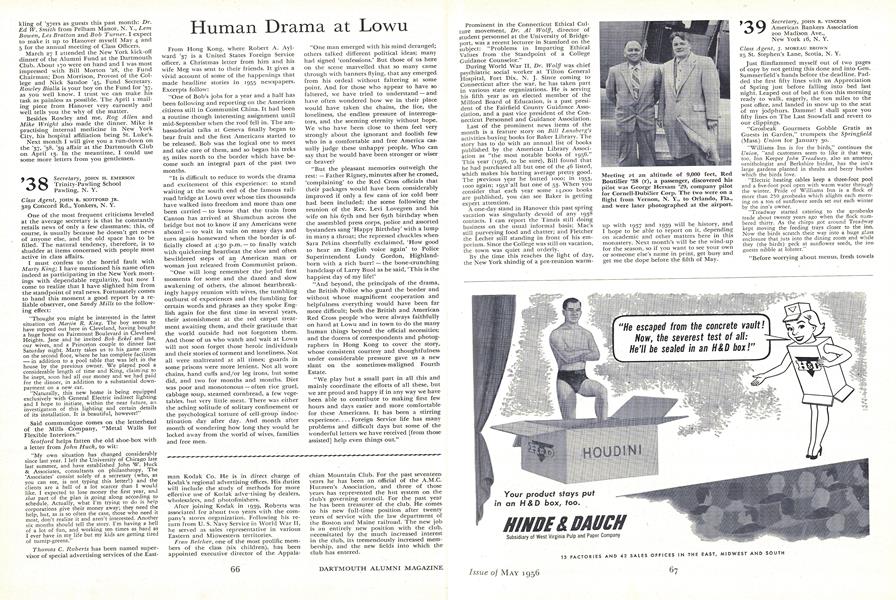

From Hong Kong, where Robert A. Aylward '37 is a United States Foreign Service officer, a Christmas letter from him and his wife Meg was sent to their friends. It gives a vivid account of some of the happenings that made headline stories in 1955 newspapers. Excerpts follow:

"One of Bob's jobs for a year and a half has been following and reporting on the American citizens still in Communist China. It had been a routine though interesting assignment until mid-September when the roof fell in. The ambassadorial talks at Geneva finally began to bear fruit and the first Americans started to be released. Bob was the logical one to meet and take care of them, and so began his treks 25 miles north to the border which have become such an integral part of the past two months.

"It is difficult to reduce to words the drama and excitement of this experience: to stand waiting at the south end of the famous railroad bridge at Lowu over whose ties thousands have walked into freedom and more than one been carried - to know that the train from Canton has arrived at Shumchun across the bridge but not to know if any Americans were aboard - to wait in vain on many days and turn again homeward when the border is officially closed at 4:30 p.m. - to finally watch with quickening heartbeat the slow and often bewildered steps of an American man or woman just released from Communist prison.

"One will long remember the joyful first moments for some and the dazed and slow awakening of others, the almost heartbreakingly happy reunion with wives, the tumbling outburst of experiences and the fumbling for certain words and phrases as they spoke English again for the first time in several years, their astonishment at the red carpet treatment awaiting them, and their gratitude that the world outside had not forgotten them. And those of us who watch and wait at Lowu will not soon forget those heroic individuals and their stories of torment and loneliness. Not all were maltreated at all times; guards in some prisons were more lenient. Not all wore chains, hand cuffs and/or leg irons, but some did, and two for months and months. Diet was poor and monotonous - often rice gruel, cabbage soup, steamed cornbread, a few vegetables. but very little meat. There was either the aching solitude of solitary confinement or the psychological torture of cell-group indoctrination day after day. And month after month of wondering how long they would be locked away from the world of wives, families and free men.

"One man emerged with his mind deranged; others talked different political ideas; many had signed 'confessions.' But those of us here on the scene marvelled that so many came through with banners flying, that any emerged from his ordeal without faltering at some point. And for those who appear to have so faltered, we have tried to understand - and have often wondered how we in their place would have taken the chains, the lice, the loneliness, the endless pressure of interrogators, and the seeming eternity without hope. We who have been close to them feel very strongly about the ignorant and foolish few who in a comfortable and free America cas- ually judge these unhappy people. Who can say that he would have been stronger or wiser or braver?

"But the pleasant memories outweigh the rest: - Father Rigney, minutes after he crossed, 'complaining' to the Red Cross officials that their packages would have been considerably improved if only a few cans of ice cold beer had been included; the scene following the reunion of the Rev. Levi Lovegren and his wife on his 67th and her 65th birthday when the assembled press corps, police and assorted bystanders sang 'Happy Birthday' with a lump in many a throat; the repressed chuckles when Sara Pekins cheerfully exclaimed, 'How good to hear an English voice again' to Police Superintendent Lundy Gordon, Highlandborn with a rich burr! - the bone-crunching handclasp of Larry Buol as he said, 'This is the happiest day of my life!'

"And beyond, the principals of the drama the British Police who guard the border and without whose magnificent cooperation and helpfulness everything would have been far more difficult; both the British and American Red Cross people who were always faithfully on hand at Lowu and in town to do the many human things beyond the official necessities; and the dozens of correspondents and photographers in Hong Kong to cover the story,, whose consistent courtesy and thoughtfulness. under considerable pressure gave us a new slant on the sometimes-maligned Fourth Estate.

"We play but a small part in all this and mainly coordinate the efforts of all these, but we are proud and happy if in any way we have been able to contribute to making first few hours and days easier and more comfortable for these Americans. It has been a stirring experience.... Foreign Service life has many problems and difficult days but some of the wonderful letters we have received [from those assisted] help even things out."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureD C U

May 1956 By GEORGE H. KALBFLEISCH, -

Feature

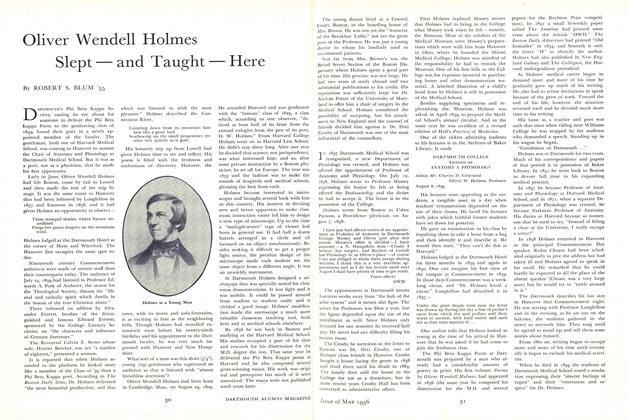

FeatureOliver Wendell Holmes Slept – and Taught – Here

May 1956 By ROBERT S. BLUM '55 -

Feature

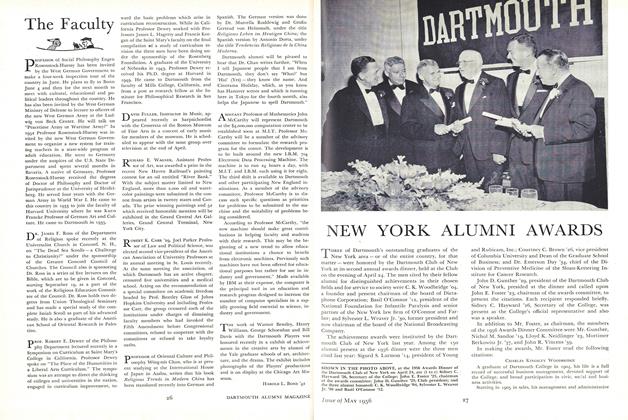

FeatureNEW YORK ALUMNI AWARDS

May 1956 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1956 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, THEODORE D. SHAPLEIGH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

May 1956 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR, RICHARD EBERHART '26