It is a well-established custom that one Sunday in June, Dartmouth College sits back to reflect on its latest brood of collegiate four-year-olds - grand, old seniors who have earned the right to wear caps and gowns. Because it is a graduation exercise, it is also customary to look back over the four years and consider what has happened. Most of us remember that we were visited by Janet Pilgrim and written up in Playboy magazine. Some few of us probably also remember that we were visited by Dame Edith Sitwell and written up in Holiday. But because this exercise is also named Commencement, I should like to look for a moment at what is beginning - to look at that wide, wide world into which this black brood of fledglings must go.

In 1664, almost 70,000 people, about one-sixth of the population of London, were wiped out by plague. Devastating? Not very, when we consider that in 1945, Hiroshima counted 130,000 people among its casualties from the atomic bomb, more than one-third its total population. Effective? No. What it took the plague eleven months to do, nuclear fission did between 9:15 and 9:30 one Monday morning. Serious? Not very serious. Two years later the plague was a memory. We still don't know the full effects of Hiroshima. Deadly? No, not even that. Most of the Londoners in 1664 were able to get out of London away from danger. From the atomic bomb, there is "no place to hide." Here is the new world which was discovered on August sixth, twelve years ago. No one doubts that this age of the atom heralds the dawn of a new era. The question is, will the sun have a chance to rise before night? We have reached the point of no return.

Bubonic plague doesn't worry us very much today. While we were at Dartmouth we saw polio licked. The battle against cancer is being fought and will be won. Nature, it seems, can be controlled by man's relentless will. But what of man? Every progress against disease has been matched by progress in destructive power. As Nature has become ineffective, man has stepped into the breach with death-giving force no natural phenomenon could ever claim. This too is the new world. Limitless scientific advance which goes forward and backward at the same time. And again the alert thinker faces a question. Which way are we really heading?

The world into which today's graduate steps is a complex one, with a nuclear sword of Damocles hanging over his head and an uncontrollable scientific, materialistic rush which, whatever way it is going, cannot be checked. With what must we be equipped to create that world as we would like it to be? The past four years have been designed to equip us for the job of being. As our own becoming ends this morning, we are expected to join hands and take part in the world's endless becoming.

I suggest that first we need courage. Not the courage for which medals are given; only a few men can lead armies and a few men are not enough. What is needed is the courage to stand up and say, "I am myself. Whatever I am - right or wrong - I am myself." It was this sort of courage which told a peasant girl named Joan to say to all the assembled knowledge of her age, "I do not wish to deny my Voices. What I have done I shall never wish to undo." Why is this needed today more than ever before? Because when men begin to forget the worth of man, when a man's intrinsic value appears less important than a battle marker or a boundary line, then must men stand up and reaffirm themselves. In times like these men must be reminded that they are men and men are worth something - not because they can solve a problem in algebra, nor even because they can solve the riddles of the universe, but because they are men. This is the lesson we have lost today, and unless each man has the courage to declare himself for what he is, it will be lost forever.

I suggest that we need respect; respect for the man to the right and to the left, respect for the man who agrees and for the man who disagrees. We must be men who say, "I think that I am right, but I know that I may be wrong. I shall obey myself but never shall I call another man to obey me in disobedience to himself. I shall judge myself, but none other." This is the great heart of our nation - the understanding that each man's duty is to his own conscience. At the end of the Constitutional Convention, Benjamin Franklin noted that the sun painted on the back of General Washington's chair was unquestionably a "rising and not a setting sun." And why? Because the dele- gates had not imitated that French lady he knew who, in a dispute with her sister, said, "I don't know how it happens, sister but I meet with nobody but myself that's always in the right." Why this respect for those with whom we disagree, when the dangers of error are incalculable? For just that reason. Because we may be holding to something false and it will only be seen if someone proclaims that which is true. Because we have not consistently been right and it matters terribly if we are very wrong for too long. Someone has said, "Man has had the happy privilege of believing that he knows everything when he knows almost nothing." We no longer have that privilege. Only if we put all our heads together can we survive.

I suggest that we need involvement. In the eighteenth century it didn't make a great deal of difference whether any one man thought fires were caused by phlogiston or oxygen. The shoemaker could tend to his last and leave the bread to the baker. Today mass indifference will be fatal. Not to vote is to commit suicide, for more truly than ever before, we are placing our lives in the hands of our representatives. To ignore a hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific because it is two thousand miles away is blindness when scientists are still wondering about the effects such testing may have on our children. And to disregard a speech because it is in a foreign language or a flood because it is the Ganges and not the Mississippi that is overflowing is to invite destruction when bombs can be launched across oceans. Man's genius has brought the world together; he must use his genius to keep it from falling apart. We must be concerned about that which concerns us and the truth is that today, everything does.

I suggest that we need wisdom. This is not the first time men have been in danger. It is not the first time the obstacles seemed too great and the demands too high. We have the record of the past; we must learn to use it. In books and experiments there are duplicated for us the important experiences of men who faced their own insuperable problems and solved them. These are the facts; we must gather and assimilate them. More than that, we must evaluate them through the perspective of time. It is not enough to find the pattern of the past. We must use it to work out a pattern for the future. Knowledge must become wisdom. Why a special call for wisdom, which has always been necessary? Because today we are playing for final, stakes; the chips are down and we haven't any more. Men have been in danger before,; but when they failed because they were not wise, other men could pick up the fight. If we fail today, then the record of man will end in failure. When the chain reaction was discovered we lost the ability to keep the other parts going when one part fails. And so today especially, we need wisdom, because the game will be won or lost on one throw of the dice. If we lose, no one will be there to throw again.

I suggest that we need faith. I have not painted a happy picture these past few minutes. Only a Rip Van Winkle asleep for twenty years could look brightly at the world around him. But we are "this happy breed." We are men, and men have climbed Mount Everest. We are men, those strange, comic beings who seem to delight in throwing themselves into a pit, just for the fun of climbing out. And we do climb out, usually to stand higher than before. So faith is possible. Not the blind faith of a Dr. Pangloss. This is not the "best of all possible worlds." But it's the only one we've got and we have to make do. That faith is possible which, recognizing the danger, sees the hopeful possibility and is determined to make it real. Why a call for special faith today? Because the times are troubled, more than they have ever been, and men have been known to conquer by faith.

And so we come back to June 1957, on a Sunday morning. We who graduate have inherited the past. We have inherited fearsome dangers and burdens. But ours too are the accomplishments and achievements. Ours are, the deeds of Joan and the words of Ben Franklin. In fine, ours is the record of man. With it goes the privilege of inhabiting the future as we shall make it. It is an. awesome responsibility. We hold in our hands the capacity to end the record forever, to blot out the sun and leave only the explosive glare of total destruction for men to see by. But if we have the courage to be men and have respect for the courage of others, if we involve ourselves with the world and react to it with wisdom, if we have the determined faith that we shall not fail, our responsibility can be met, With these things, we • shall-.be able to look on tomorrow with confidence, and meet the day, as a new day should always be met, with hope.

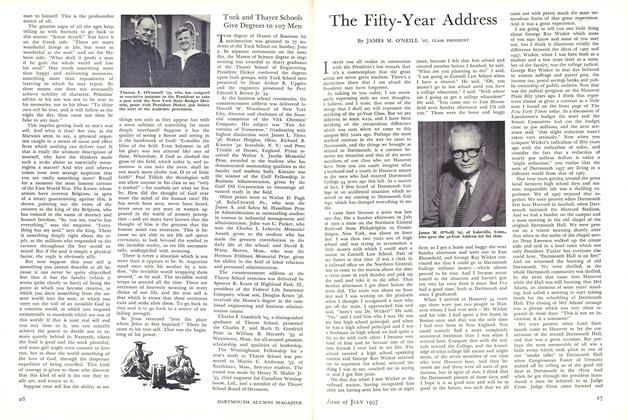

Weinreb delivering the 1957 Valedictory

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHopkins Center and Dartmouth Hall

July 1957 By CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Feature

FeatureThe Commencement Address

July 1957 By DOUGLAS HORTON, D.D. '57 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1957 By JAMES M. O'NEILL '07 -

Feature

FeatureThe Honorary Degree Citations

July 1957 -

Feature

FeatureThe 1957 Commencement

July 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1957 By DONALD D. MCCUAIG '54

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe 1961 Alumni Awards

July 1961 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

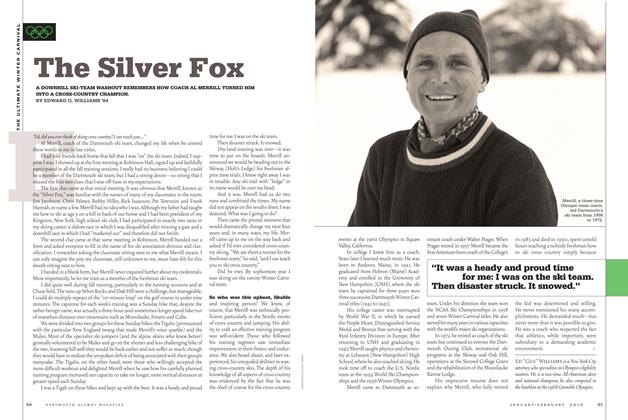

FeatureThe Silver Fox

Jan/Feb 2010 By EDWARD G. WILLIAMS ’64 -

Feature

FeatureFor The Sake Of Argument

February 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1951 By SIR HAROLD CACCIA -

Feature

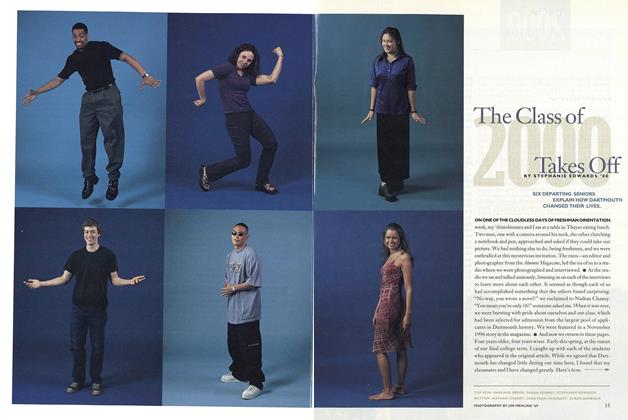

FeatureThe Class of 2000 Takes Off

JUNE 2000 By STEPHANIE EDWARDS ’00