ANY WORTHWHILE INSTITUTION of higher education, one college president has said, lives "in chronic tension with the society that supports it." Says The Campus and the State, a 1959 survey of academic freedom in which that president's words appear: "New ideas always run the risk of offending entrenched interests within the community. If higher education is to be successful in its creative role it must be guaranteed some protection against reprisal..."

The peril most frequently is budgetary: the threat of appropriations cuts, if the unpopular ideas are not abandoned; the real or imagined threat of a loss of public even alumni—sympathy.

Probably the best protection against the danger of reprisals against free institutions of learning is their alumni: alumni who understand the meaning of freedom and give their strong and informed support to matters of educational principle. Sometimes such support is available in abundance and offered with intelligence. Sometimes—almost always because of misconception or failure to be vigilant—it is not.

For example:

An alumnus of one private college was a regular and heavy donor to the annual alumni fund. He was known to have provided handsomely for his alma mater in his will. But when he questioned his grandson, a student at the old school, he learned that an economics professor not only did not condemn, but actually discussed the necessity for, the national debt. Grandfather threatened to withdraw all support unless the professor ceased uttering such heresy or was fired. (The professor didn't and wasn't. The college is not yet certain where it stands in the gentleman's will.)

When no students from a certain county managed to meet the requirements for admission to a southwestern university's medical school, the county's angry delegate to the state legislature announced he was "out to get this guy"—the vice president in charge of the university's medical affairs, who had staunchly backed the medical school's admissions committee. The board of trustees of the university, virtually all of whom were alumni, joined other alumni and the local chapter of the American Association of University Professors to rally successfully to the v.p.'s support.

When the president of a publicly supported institution recently said he would have to limit the number of students admitted to next fall's freshman class if high academic standards were not to be compromised, some constituent-fearing legislators were wrathful. When the issue was explained to them, alumni backed the president's position—decisively.

When a number of institutions (joined in December by President Eisenhower) opposed the "disclaimer affidavit" required of students seeking loans under the National Defense Education Act, many citizens—including some alumni—assailed them for their stand against "swearing allegiance to the United States." The fact is, the disclaimer affidavit is not an oath of allegiance to the United States (which the Education Act also requires, but which the colleges have not opposed). Fortunately, alumni who took the trouble to find out what the affidavit really was apparently outnumbered, by a substantial majority, those who leaped before they looked. Coincidentally or not, most of the institutions opposing the disclaimer affidavit received more money from their alumni during the controversy than ever before in their history.

IN THE FUTURE, as in the past, educational institutions worth their salt will be in the midst of controversy. Such is the nature of higher education: ideas are its merchandise, and ideas new and old are frequently controversial. An educational institution, indeed, may be doing its job badly if it is not involved in controversy, at times. If an alumnus never finds himself in disagreement with his alma mater, he has a right to question whether his alma mater is intellectually awake or dozing.

To understand this is to understand the meaning of academic freedom and vitality. And, with such an understanding, an alumnus is equipped to give his highest service to higher education; to give his support to the principles which make higher education free and effectual.

If higher education is to prosper, it will need this kind of support from its alumni—tomorrow even more than in its gloriously stormy past.

Ideas are the merchandise of education, and every worthwhile educational institution must provide and guard the conditions for breeding them. To do so, they need the help and vigilance of their alumni.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe TPC Planning Program

April 1960 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Feature

FeatureEverything But Little Dogies

April 1960 By WARREN BLACKSTONE '62, PETE BOSTWICK '63 -

Feature

FeatureTHE ALUMNUS/A

April 1960 -

Article

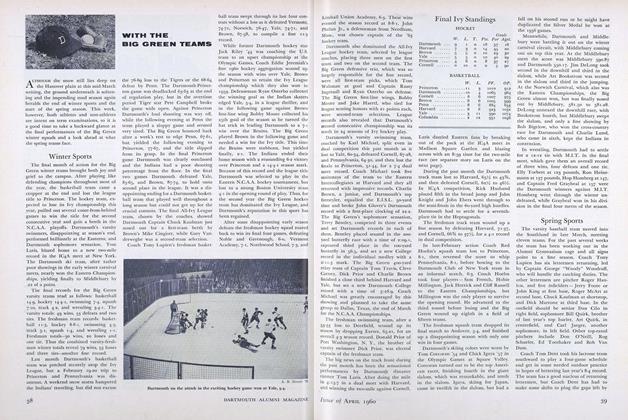

ArticleWinter Sports

April 1960 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

April 1960 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1951

April 1960 By LOYE W. MILLER, JAMES V. ROBINSON