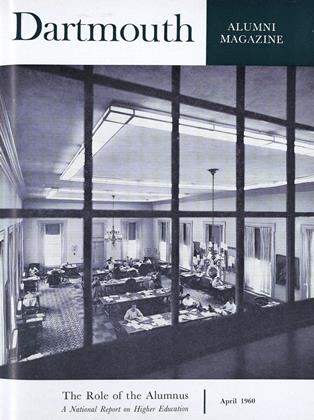

WHITHER THE COURSE of the relationship between alumni and alma mater? At the turn into the Sixties, it is evident that a new and challenging relationship—of unprecedented value to both the institution and its alumni—is developing.

If alumni wish, their intellectual voyage can becontinued for a lifetime.

There was a time when graduation was the end. You got your diploma, along with the right to place certain initials after your name; your hand was clasped for an instant by the president; and the institution's business was done.

If you were to keep yourself intellectually awake, the No-Doz would have to be self-administered. If you were to renew your acquaintance with literature or science, the introductions would have to be self-performed.

Automotion is still the principal driving force. The years in school and college are designed to provide the push and then the momentum to keep you going with your mind. "Madam, we guarantee results," wrote a college president to an inquiring mother, "—or we return the boy." After graduation, the guarantee is yours to maintain, alone.

Alone, but not quite. It makes little sense, many educators say, for schools and colleges not to do whatever they can to protect their investment in their studentswhich is considerable, in terms of time, talents, and money—and not to try to make the relationship between alumni and their alma maters a two-way flow.

As a consequence of such thinking, and of demands issuing from the former students themselves, alumni meetings of all types—local clubs, campus reunions—are taking on a new character. "There has to be a reason and a purpose for a meeting," notes an alumna. "Groups that meet for purely social reasons don't last long. Just because Mary went to my college doesn't mean I enjoy being with her socially—but I might well enjoy working with her in a serious intellectual project." Male alumni agree; there is a limit to the congeniality that can be maintained solely by the thin thread of reminiscences or smalltalk.

But there is no limit, among people with whom their education "stuck," to the revitalizing effects of learning. The chemistry professor who is in town for a chemists' conference and is invited to address the local chapter of the alumni association no longer feels he must talk about nothing more weighty than the beauty of the campus elms; his audience wants him to talk chemistry, and he is delighted to oblige. The engineers who return to school for their annual homecoming welcome the opportunity to bring themselves up to date on developments in and out of their specialty. Housewives back on the campus for reunions demand—and get—seminars and short-courses.

But the wave of interest in enriching the intellectual content of alumni meetings may be only a beginning. With more leisure at their command, alumni will have the time (as they already have the inclination) to undertake more intensive, regular educational programs.

If alumni demand them, new concepts in adult education may emerge. Urban colleges and universities may step up their offerings of programs designed especially for the alumni in their communities—not only their own alumni, but those of distant institutions. Unions and government and industry, already experimenting with graduate-education programs for their leaders, may find ways of giving sabbatical leaves on a widespread basis and they may profit, in hard dollars-and-cents terms, from the results of such intellectual re-charging.

Colleges and universities, already overburdened with teaching as well as other duties, will need help if such dreams are to come true. But help will be found if the demand is insistent enough.

Alumni partnerships with their alma mater, inmeeting ever-stiffer educational challenges, will groweven closer than they have been.

Boards of overseers, visiting committees, and other partnerships between alumni and their institutions are proving, at many schools, colleges, and universities, to be channels through which the educators can keep in touch with the community at large and vice versa. Alumni trustees, elected by their fellow alumni, are found on the governing boards of more and more institutions. Alumni "without portfolio" are seeking ways to join with their alma maters in advancing the cause of education. The representative of a West Coast university has noted the trend: "In selling memberships in our alumni association, we have learned that, while it's wise to list the benefits of membership, what interests them most is how they can be of service to the university."

Alumni can have a decisive role in maintaininghigh standards of education, even as enrollmentsincrease at most schools and colleges.

There is a real crisis in American education: the crisis of quality. For a variety of reasons, many institutions find themselves unable to keep their faculties staffed with high-caliber men and women. Many lack the equipment needed for study and research. Many, even in this age of high student population, are unable to attract the quality of student they desire. Many have been forced to dissipate their teaching and research energies, in deference to public demand for more and more extracurricular "services." Many, besieged by applicants for admission, have had to yield to pressure and enroll students who are unqualified.

Each of these problems has a direct bearing upon the quality of education in America. Each is a problem to which alumni can constructively address themselves, individually and in organized groups.

Some can best be handled through community leadership: helping present the institutions' case to the public. Some can be handled by direct participation in such activities as academic talent-scouting, in which many institutions, both public and private, enlist the aid of their alumni in meeting with college-bound high school students in their cities and towns. Some can be handled by making more money available to the institutions—for faculty salaries, for scholarships, for buildings and equipment. Some can be handled through political action.

The needs vary widely from institution to institution - and what may help one may actually set back another. Because of this, it is important to maintain a close liaison with the campus when undertaking such work. (Alumni offices everywhere will welcome inquiries.)

When the opportunity for aid does come—as it has in the past, and as it inevitably will in the years ahead - alumni response will be the key to America's educational future, and to all that depends upon it.

The of keeping intellectually alive for a lifetime will be fostered more than ever by a growing alumni-alma mater relationship.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe TPC Planning Program

April 1960 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Feature

FeatureEverything But Little Dogies

April 1960 By WARREN BLACKSTONE '62, PETE BOSTWICK '63 -

Feature

FeatureTHE ALUMNUS/A

April 1960 -

Article

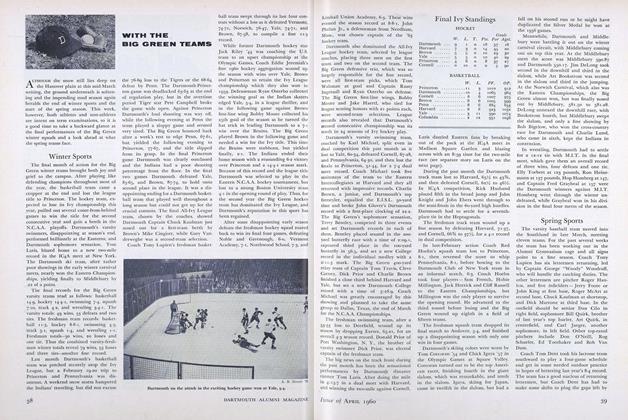

ArticleWinter Sports

April 1960 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

April 1960 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1951

April 1960 By LOYE W. MILLER, JAMES V. ROBINSON