THE death of Bill Cunningham '19 on April 17, after a gallant fight against cancer, took from the Dartmouth family one of its best known and most colorful figures. Into the lore of the College will go many a classic newspaper story he wrote about Dartmouth, especially in the field of sports. As representative of Bill Cunningham's unique and vivid style, best under the pressure of on-the-spot reporting, we reprint here a part of the account of the 1938 Dartmouth-Yale football game he wrote for the old Boston Post.

NEW HAVEN, Oct. 29 - Led by his own spectacular play, Captain Bob MacLeod's 1938 Indian eleven became the first football unit in all Dartmouth history to make it a seasonal grand slam over Princeton, Harvard and Yale in the mammoth circular cavern of the Bulldog here today. The numerical margin was 24-6 in credit of the Hanover heathen, and but for the fact that Sachem Blaik called off his regulars just before the end of the third chapter, both to save them for Cornell and to give his seconds and thirds a taste of big time cannon flame, the score might have gone on into basketball figures, for the Big Green backs were truly tearing and likewise r'aring by, and Yale, although game and gallant, was back on its heels.

A town and bowl cramming throng of 70,000 spectators encircled the, at times, dragging drama on the lime laddered quadrangle, in a gusty, but otherwise flawless afternoon and saw the Dartmouth contingent, after a characteristically jittery first period in which it huffed and puffed and fumbled and stumbled, finally get a seat in the saddle and really start to ride.

MacLeod was the spark plug, the spearhead, the ne plus ultra of the effort. The tall, streamlined 190 pounder out of Glen Ellyn, Ill., set up the first touchdown near the end of the first period, by snaring a hard, burning pitch from Bombshell Bill Hutchinson to move the Green down from midfield to Yale's 25, from which stance Hutchinson and Howe slashed and aerialized along until Howe punched it across on the third play of the second canto.

But it was the Glen Ellyn gazelle in person and in toto who scored the other two Dartmouth touchdowns within 8 minutes of each other in the following period with brilliant sprints off tackle on straight running plays, the first being a 47-yard masterpiece of art in the broken field. The second being a 21-yarder, through a bewildered, outguessed and outrun Yale secondary which didn't get close enough to tell the color of his eyes.

The other Dartmouth marker, a 34-yard field goal, was a contribution of the noble seconds, who galloped on en masse three plays before the third period ended and who carried the white man's burden from there until the end of the ball game. Phil Dostal, the tackle, toed the melon through the gallows, with young Killer-Diller Krieger in the prayerful attitude on the award. The seconds had penetrated as far as Yale's 11-yard line, but off side penalties ruined them, and it was fourth downeight on Yale's 15 when this emergency measure was resorted to....

But, speaking of the Gates of Mercy or other sundry sorts, probably the biggest story on this ball field today centres around the perhaps unprecedented story of Harry Gates, the veteran Dartmouth quarterback, who played in three periods of this battle, although only in part of each.

Captain Robert MacLeod, with his two touchdowns, his brilliant, spark-shedding runs, his terrific tackling and inspirational leadership is the official hero of what to Dartmouth will always be a historic game, but the unsung hero and the contributor of the more amazing, if less spectacular, performance is the former Saugus High School star, who after being out of athletics for practically a year, played an all-important part in this ball game today with only two days of practice, and those two days mostly standing around and looking on.

After Dartmouth's Columbia game last year, Gates apparently made up his mind to retire from football. Soon after entering college he became deeply interested in religion and apparently experienced some emotional conflict wherein it became impossible for him to compromise the fuss, the fanfare, the carnival tempo of football with the simplicity and the meditation which seemed to him much more important....

On Wednesday of this week, as suddenly as he left, he came back again. If there's any particular story to his change of heart nobody's revealed it. But here he was. He said he wanted a suit, that he'd like to try it out for awhile and if he couldn't get back in shape, or the Dartmouth coaches didn't think he could fit into their present scheme he'd give it up again.

He was hard and lean and he seemed to have his old speed. The plays had changed a little. He stood around and watched them for awhile. Then he took his old place at quarterback and ran a few signals.

At his own request he stepped in for a few plays at scrimmage. That was Wednesday. He ran signals again on Thursday, taking his turn with the other quarterbacks, Nopper and Courter, and down here yesterday in what is little more than loosening up exercises he ran around the sward with the varsity squad.

It was understood that he was along more or less as a visitor and would see his first real action, if any, against Cornell two weeks from now.

But in football, perhaps more than in other human endeavors, the best-laid plans of mice and men gang aft agley. In fact, that's one of the main ideas of the game, and this particular ball game early developed into anything else than what Dartmouth was expecting. The Green expected Yale's talented forward passer, Gil Humphrey, to throw a million forward passes.

In fact, after they started the proceedings by kicking off to the Blue, they settled themselves into a five-man line, giving three close secondarians to defend against air shots.

But instead of taking to the air, the fiery little Yale field marshal suddenly began running with the football. Both because the Green was set for a pass defence and because their line was spaced too tightly, Yale began to walk right down the field on the Green in what amounted to a steady parade.

Even with the strong wind at her back, Dartmouth couldn't get the ball out past her own 25-yard line and the first period wasn't even well started before Yale, with Humphrey and Wilson carrying, had marched from the Yale 37 to the Dartmouth 30 in a steady and uninterrupted parade.

The Dartmouth ends, tackles and close backers-up seemed helpless to stop this relentless march, and it looked as if a touchdown were surely on the way. The Yale backs were driving 10 yards at a clip. The Green looked bewildered and groggy.

The hard-to-stop Humphrey had just swung Dartmouth's left end for 10 yards and first down on approximately Dartmouth's 30, and the Green had taken out time to rally her scrambled wits, when out from the Dartmouth bench galloped Gates, the varsity veteran with two days' practice. He was so new and his presence so unexpected that his name didn't even appear in the programme, and most of the throng, even the Dartmouth throng, had no idea of who No. 73 was nor what sort of story was behind him.

Taking Nopper's place at quarterback, he went behind that line with Centre Bob Gibson, and when Yale started again, they discovered they'd run into dynamite. Two line smashes didn't gain five yards. The two G's - Gibson and Gates - crashed those plays so hard, the Yale carriers arose as if a house had fallen on 'em.

Then Mr. Humphrey tried to take to the air. This was no good either. On two consecutive attempts he couldn't find an uncovered target, and Dartmouth took the ball on downs on her 25-yard line and started from there.

As nearly as it can be said that one person did it, Mr. Gates stopped Yale on the march and turned that ball game around. For here comes the rest of the amazing performance, for he did turn that ball game around.

The Green hadn't been able to move out of its own shadow until Gates took over as quarterback. Shortly thereafter they got the ball at midfield when Colby Howe, the wild horse of the backfield, intercepted a Yale pass, and from there, with Gates quarterbacking and contributing the sort of blocking Dartmouth's been needing, the Green got into gear, moving steadily from the 50 to Yale's 12 as the period ended, and as soon as goals were switched, going on for the game's initial touchdown.

Gates stayed in the ball game until about the middle of the second period, when he gave way to Nopper and received a tremendous ovation leaving the field, for word about him had apparently spread.

The score was still 7-0 in favor of Dartmouth, and the Green had just lived through two miserable breaks, a 65-yard sprint to Yale's 5 with a punt by MacLeod, which was nullified by a clipping penalty and a ball-losing fumble by Howe on the Green's 34 - but Yale finally fell victim, in turn, to a sour break when a 15-yard penalty for holding pulled her back to her own 10, forcing Humphrey to kick into the teeth of the wind.

Here, Gates came tearing back into the ball game again.

That first time, he'd come to the rescue defensively. This time he came as an offensive assistant, when the Green should get the ball. That was practically immediately. Humphrey punted out to Howe and the flying Dartmouth safety ran the ball back five to Yale's 47.

On the first play, Gates called Dartmouth's famous 55, the favorite play of the team last year, and of the famous '36 team before it. That's the off-tackle play with MacLeod carrying the leather. Gates called his captain's signal, the team set. In his high piping treble, he sang the starting signals in a voice plainly audible in the high and distant press box.

In a flash, and looking like it used to, but hasn't thus far this year, the play started with its swing to the left, and Gates, spear heading it, threw that first and all important block at the Yale right end. It was one of those copyrighted blocks of his that irons the opposition as flat as a flitter. Yale's Mr. Moody was erased from the path of MacLeod as completely as if he'd never existed. The Dartmouth end, Whit Miller, drove the Yale tackle, Brooks, back on his haunches and in toward centre. Bombshell Bill Hutchinson crashed the Yale backer-up.

And there went MacLeod into the open like a scared jack-rabbit, only three times as fast.

All that young gentleman needs is a fissure to whizz through. Once in the open he's lightning. Three Yale backs, Miller, Humphrey and Collins tried to head him, pen him and finally catch him. They didn't have as much chance as a bowlegged girl in the follies. He streamed 47 yards to a clean standup touchdown.

Not three minutes later, Dartmouth scored again. Howe made the opportunity by racing 35 yards on a spinner inside Yale's left tackle. MacLeod scored the touchdown on a 21-yard sprint, exactly like the other play only for about half the other's distance. It was the self same play, with the burly Gates again throwing the block that took care of the end and gave his captain a chance.

That's the sort of running MacLeod hasn't been able to do because he had nobody to give him that needed early assistance.

Gates left the ball game shortly after that second touchdown.

He'd stopped, or he'd had an almighty part in stopping that Yale first period march to a touchdown and he'd had a powerful part in the creation of Dartmouth's three scores.

And all this from a man who's been out of all athletics for a year, with the exception of the last two or three days. The world is big, the teams are many, and there's been a lot of football. Maybe somebody, somewhere, has duplicated, or perhaps even surpassed this feat somewhere before, but to the knowledge of this historian, this is the first time any player ever entered a game of this ruggedness and importance with such little preparation and played such a major role.

He didn't seem even to have his haircomb disarranged when he trotted out that second time either, to a thunder of applause that rang from the Yale as well as the Dartmouth pavilions.

That was the major drama of the ball game, to one who knew the story, but of course, there was plenty more to the ball game.. ..

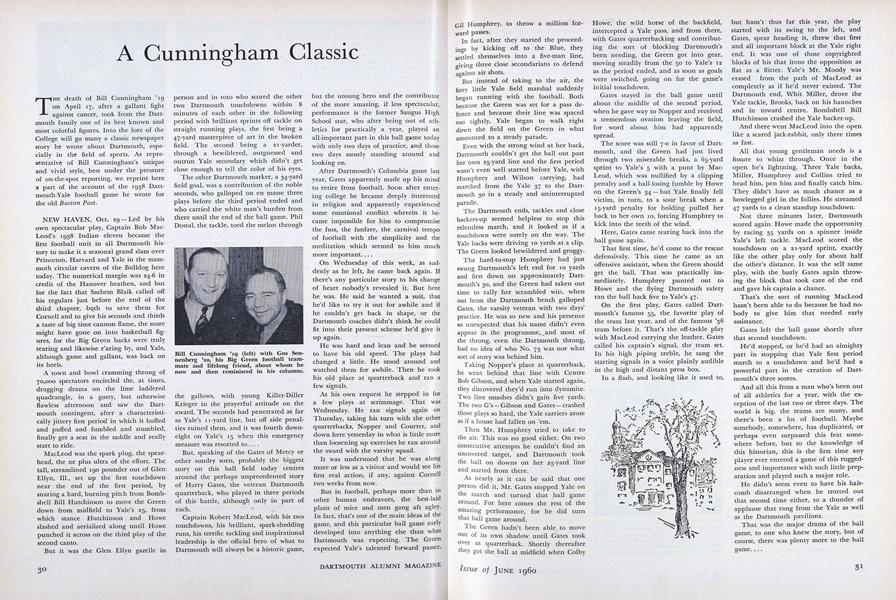

Bill Cunningham '19 (left) with Gus Sonnenberg '20, his Big Green football teammate and lifelong friend, about whom he now and then reminisced in his columns.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Thinking Man's TV Journalist

June 1960 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

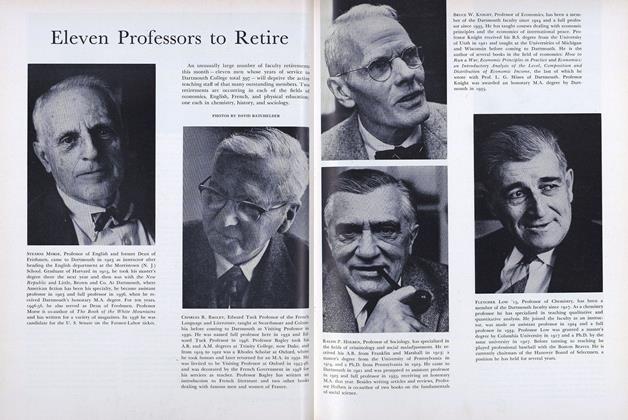

FeatureEleven Professors to Retire

June 1960 -

Feature

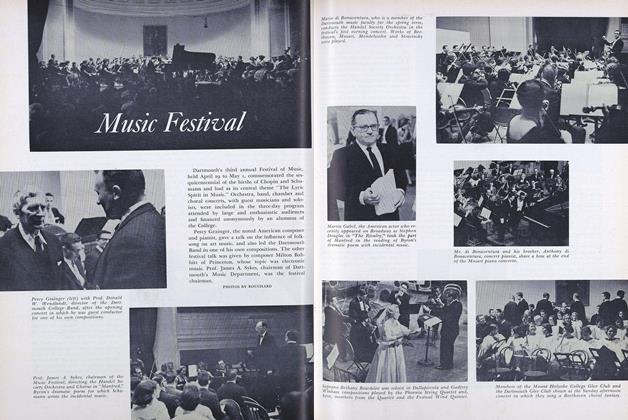

FeatureMusic Festival

June 1960 -

Article

ArticleDeaths

June 1960 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1960 By CHARLES M. DONOVAN, GEORGE B. MUNROE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938

June 1960 By MARTIN R. KING, ROBERT S. STEARNS

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePROF. JOHN G. KEMENY CHOSEN AS DARTMOUTH'S 13TH PRESIDENT

FEBRUARY 1970 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRich Brown James Matthews David Gelhar

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

FeatureA Scientific Centennial for Dartmouth

OCTOBER 1969 By ALLEN L. KING -

Feature

FeatureChange and Challenge

JULY 1965 By HAROLD KING DAVISON '15 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO PACK LIKE A PRO

Sept/Oct 2001 By NELSON ARMSTRONG '71 -

Feature

FeatureThe Rise and Fall of Humanity

MARCH 1970 By WILLIAM W. BALLARD '28