Edited by Hyde Cox and Edward Connery Lathem '51. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 1966. 119 pp.$4.50.

"The editors of this volume were both his intimate friends and knew him well enough to write a book about him, but remembering his preference - and sharing it - have chosen instead to present the man himself, as his prose reveals him."

This statement is an earnest of the tact and wisdom of the editing as well as of the distinction of what is edited. Robert Frost spoke a great deal of prose in his life and knew that he was speaking it; but he wrote comparatively little, though he supposed that when he was about 90 he'd begin to write it. His prose is as characteristic as his poetry; only he, not any one else, could have written it. It has the same sound of a voice speaking, the concentration, the unpredictability of the verse.

The slim volume has considerable variety, including a piece about baseball. But naturally much of what he wrote was about poetry, and surely no one was better fitted for this. A younger poet once asked him why he never mentioned him in his "talks." Frost replied tartly that the only poets he ever talked about on the platform were himself and Shakespeare. This, of course, was hyperbole; but his jealousy of his contemporaries was amply revealed in his conversations as well as in his letters. It is hardly surprising, then, to find traces of Shakespeare, the word play, for instance, in these pages - including a paragraph on a sonnet which is a luminous recreation of the poetic process at work.

What may be surprising, though, to those who took Frost's "jealousy" too seriously is what he has to say on contemporary poets: on Edward Thomas, who was a great friend; and on Amy Lowell, who was also a friend but one kept at a distance; and especially on E. A. Robinson, about whom he is discriminating, perceptive, and whole-heartedly appreciative. The piece "On Emerson" is the best brief distillation of Emerson I have ever read. Here the skeptical Yankee doesn't dodge superlatives: he refers to "Uriel" as the best - not about the best, which was the way he liked to hedge his praise - but "the best Western poem yet."

It has lately been fashionable to speak of Frost's "talks" (especially in his later years) as rambling and casual, with nuggets of wisdom, true, and flashes of insight, as well as of the notable humor, but nevertheless as the utterances of one too lazy for extended and reasoned discourse. I suspect that when his tape-recorded talks are published this delusion will be shattered. If they were lacking in "organization" they were almost always organic: delivered without notes (except for those in his head) they possessed the form which he prized and never ignored. Meanwhile we have in this volume the talk given at Amherst and published with some revision in the Amherst Graduates' Quarterly of February 1931. Here in a rich fabric are some of the most illuminating insights on poetry, science, religion (for with him there were never only "two" cultures) and on life in general by one of the truly great men of our time.

Professor of English Emeritus

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMILITARY POWER: THE FADING PERSUADER

October 1966 By LIEUTENANT GENERAL JAMES M. GAVIN -

Feature

FeatureWORLD UNDERSTANDING: A Job for Mass Communications

October 1966 By WALTER WANGER '15 -

Feature

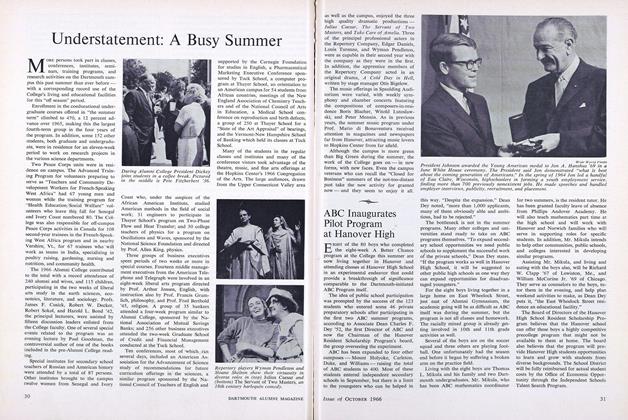

FeatureUnderstatement: A Busy Summer

October 1966 -

Feature

FeatureA Landmark Goes Down

October 1966 -

Feature

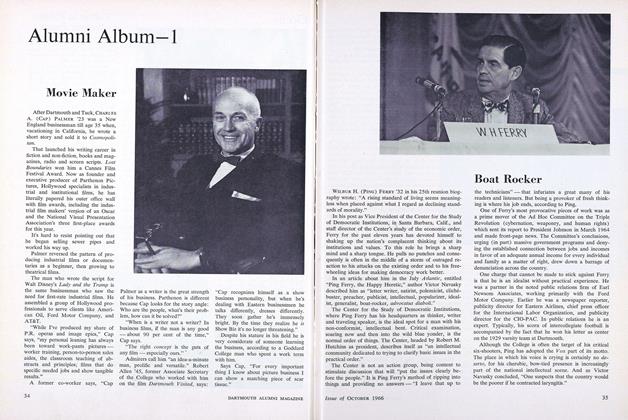

FeatureBoat Rocker

October 1966 -

Feature

FeaturePress Secretary

October 1966

STEARNS MORSE

-

Books

BooksProse Preferences.

NOVEMBER 1927 By Stearns Morse -

Books

BooksTOLSTOY

JANUARY 1929 By Stearns Morse -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN NOVEL AND ITS TRADITION.

December 1957 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksTHE LETTERS OF ROBERT FROST TO LOUIS UNTERMEYER.

JANUARY 1964 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksSELECTED LETTERS OF ROBERT FROST.

DECEMBER 1964 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksEmpty Rooms

September 1975 By STEARNS MORSE

Books

-

Books

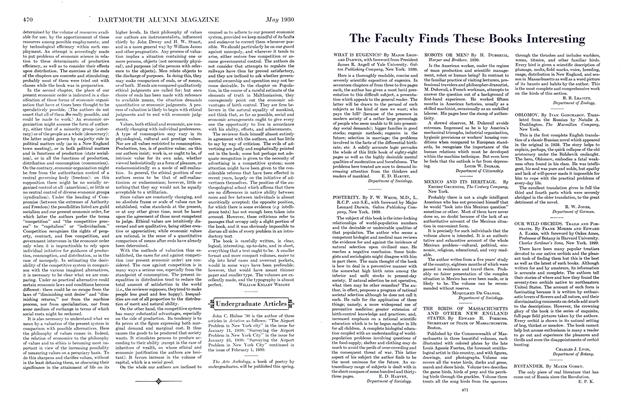

BooksThe Arts Anthology, a Book of Poetry

MAY 1930 -

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

May 1945 -

Books

BooksYES, MY DARLING DAUGHTER.

June 1937 By Benfield Pressey -

Books

BooksTHE STRUCTURE OF MATTER.

DECEMBER 1965 By FRANCIS W. SEARS -

Books

BooksSplendor

MARCH, 1928 By H. B. Preston '05 -

Books

BooksLAUGHTER AND TEARS.

FEBRUARY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21