A DARTMOUTH MEDICAL SCHOOL physiologist delivered the Charles E. Brown Memorial Lecture at the annual meeting of the American Heart Association in New York recently. It caused an even greater stir than this always-prestigious address usually does because Dr. Henry A. Schroeder reported possible and heretofore undiscovered - causes of three widespread human ailments. Then he proceeded to describe possible approaches to prevention and cure of these diseases.

The ailments are hypertension, a severe form of high blood pressure which afflicts about ten million Americans annually; atherosclerosis, hardening of the inner lining of the arteries; and diabetes.

The findings indicate that the villains may be "trace metals," tiny amounts of which can make the difference between good health and poor.

Too much cadmium in the kidneys, he reported, appears to play a role in producing hypertension. And too little chromium appears linked to diabetes and atherosclerosis.

Controlling the amounts of these trace metals might control or prevent the diseases, he said.

The findings and recommendations stem from more than ten years of meticulous, imaginative research based on statistical inferences, animal experiments, chemical analysis, and medical hunches.

Back in 1955 Dr. Schroeder found that hypertensive patients excreted abnormally large amounts of cadmium in their urine. About the same time a physicist at the University of Tennessee, Dr. Isabel H. Tipton, was analyzing chemical elements found in cadavers and determined that the kidneys contained varying ratios of cadmium to zinc, metals frequently associated in nature.

Dr. Schroeder discovered that nearly all the patients in Dr. Tipton's study who had died of hypertension had remarkably high cadmium-to-zinc ratios. Further studies of other kidneys - many from primitive parts of the world - reinforced the findings.

To further confirm the statistical relationship between cadmium and hypertension, Dr. Schroeder turned to animal experiments. He built a laboratory on a mountainside near Brattleboro, Vt., and took elaborate precautions to ensure that the experimental rats and mice were not exposed to the trace metals. The water pipes were plastic and the water deionized; the pure mountain air was electrostatically decontaminated; the all-wood structure's nails were sunk and sealed in; visitors were barred and staff members removed their shoes before entering the animal rooms.

Thousands of rats were reared in the cadmium-free environment and a series of controlled experiments began.

"When rats were given traces of cadmium in drinking water from the time of weaning," Dr. Schroeder reported, "hypertension began to appear after about a year of age, increasing in incidence with age." The disorder in rats bore a remarkable similarity to that in humans.

In another series of experiments, rats with high blood pressure caused by excessive cadmium were given a chemical agent to remove the trace metal from the body. "One week after the single injection all hypertensive rats were normal." The chemical is one that binds itself to cadmium in the body and allows it to be excreted more easily.

Similar experiments were performed to see what the role of chromium might be. Rats that were fed a chromium-deficient diet developed moderate diabetes and then atherosclerosis, much as many adult humans do. This could be cured by providing them with normal amounts of chromium.

"Furthermore," he said, "by taking advantage of the demands of the rat fetus for chromium and depleting the mother during pregnancy, we have raised five generations of rats which showed increasing incidence of diabetes.

"This strain would be considered to have a hereditary disorder were it not known to be dietary and reversed by chromium."

Dr. Schroeder concluded his lecture with this commentary: "Man's use of metals has exposed him to a number of extraneous elements by introducing them into food, water and air, and to which he and other mammals have little or no ability to adapt. Chronic diseases may result from these lifetime exposures, diseases which are not prevalent in more primitive societies. They may arise especially from those abnormal elements which accumulate with age as excesses, or from those essential elements which decline because of conditioned dietary deficiencies. Today I have presented an example of each. As usual, much more remains to be done than has been done."

Dr. Henry A. Schroeder

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

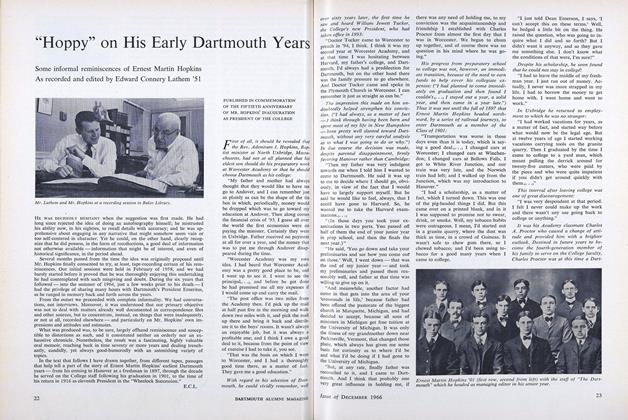

Feature"Hoppy" on His Early Dartmouth Years

December 1966 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Philosophy of Culture

December 1966 By ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32 -

Feature

FeatureContemporary Man

December 1966 -

Feature

FeatureToro's President

December 1966 -

Feature

FeatureHigh School Principal

December 1966 -

Feature

FeatureSpace Salesman

December 1966