FOR nearly 40 years I have been engaged on a self-assigned project, the end of which is not in sight, the value of which is dubious, and the origins of which escape me. I refer to the practice, begun in 1928 when I was a sophomore at Dartmouth, of making a brief record, on 3" x 5" cards, of the books I read. The cards, arranged alphabetically by authors, contain — in addition to the name of the author and the title of the book — a few words of comment, and the month and year in which I managed to read the book.

I rarely refer to the file. I am a busy international relations specialist whose career and social acceptability do not depend on a flair for commenting knowledgeably on the works of Phyllis Bentley, John Dos Passos, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Sinclair Lewis, Edna St. Vincent Millay, John Steinbeck, and others who rate six or more entries in my file. (For material that I think I might need in my work, I have other files, to which I also fail to refer.) Occasionally, my wife accuses me of having read some book that I cannot recall, or may even deny, having read — and the card file proves she is right. Once in a while it proves her wrong, but in those cases, the proof is inconclusive because I may have forgotten to fill out a card.

Why not abandon the project? What, if anything, does it reveal? How did I get into it in the first place?

I think I felt in 1928 something like Anthony Trollope felt in 1876 (though I did not discover how he felt until I read his Autobiography in April 1947):

That I can read and be happy while I am reading is a great blessing. Could I remember, as some men do, what I read, I should have been able to call myself an educated man. But that power I have never possessed. Something is always left — something dim and inaccurate — but still something sufficient to preserve the taste for more. I am inclined to think that is so with most readers.

I, too, retain only dim and inaccurate impressions. I have an extraordinary capacity for forgetting what the reviewers hail as an "unforgettable tale." I can blur the "haunting memory" of fictional triumphs and tragedies within a few weeks of the time they begin to haunt. As for those non-fictional "indispensable keys" to the understanding of ancient Greece, or modern Turkey, or life in a mid-western town, I soon lose the key. My card file serves as a refresher only if I read a second book by the same author, because I tend to refer to my comment on the first book when formulating my impressions of the second.

Once upon a time, I may also have thought that cards like the one urging me to re-read the Meditations of MarcusA urelius would inspire me to return to books that seemed worth re-reading. But that was before I acquired my scribbling friends - who write a lot faster than I can read and often honor me with copies of their manuscripts for criticism. Loyalty, intellectual curiosity, and the hope that they will reciprocate when I tune up for publication compel me to accept the challenge. In addition, there is the noon-hour browse that adds three more to the bedside table of unread books, the "must reading" that cascades into my office, and the lovingly selected birthday-Christmas-anniversary gifts that quietly cry for attention. I have on occasion re-read books that I had read many years earlier, but usually not because of notations in my card file.

Why then do I bother to maintain the file? For the same reason, I suppose, that I bothered to read Orley Farm or TheMedici or The Ordeal of Richard Feveril: slavery to a pleasant habit. Also, the satisfactions of a private project in a world in which privacy is ever harder to preserve, and impressions are piled higgledy-piggledy on one another before they can ripen into opinions. Perhaps too, kinship with the flustered woman speaker who was given a glowing build-up by the chairman and opened her speech by saying, "Mr. Chairman, after that wonderful introduction, I can hardly wait to hear what I'm going to say." My thoughts become less amorphous when I take pen in hand.

What do the cards reveal? I am a slow reader (1944-1954 for the 1600 pages of The Rise of American Civilization). The entire file contains fewer than 2,000 entries. It is relatively free of devastating comments; I dislike hurting the absent author's feelings. "Without doubt, the writer's finest book" may characterize a dreary volume by someone who never published a second.

I seem to be a carnivorous rather than an omnivorous reader. When I settle down with a book, my companion is more likely to be biography, memoirs, or modern history than a popular novel. I am a mass market for reminiscences covering the first half of the 20th Century, whether those of Norman Angell, Henry Seidel Canby, Clarence Darrow, Leonard Woolf, Freya Stark, Winston Churchill, or Harry S. Truman. I go off on short-lived forays into Flemish art or Renaissance life in Italy. If I rearranged the cards in chronological order, they might tell me more about changes in my reading habits.

I have a sustained, professional interest in the problems — economic, social, political, and aesthetic - of the developing countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Nevertheless, I am not as dedicated to self-improvement as my card file might indicate. Even a 300-page penetration into The Conquest of Peru or The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire will rate a card and a recommendation to myself that I try again after breaking my leg or a prolonged period of insomnia. On the other hand, vanity or some other foible excludes detective stories. I know that I have read at least a dozen books by Georges Simenon, but I have cards on only three, and not one of the Inspector Maigret series is mentioned in my secret archives. Perhaps the Inspector could tell me why.

The bedside reading of President Eisenhower or President Kennedy may be of interest to the general public; that of Robert E. Asher is not. My purpose is not to publicize my tastes but rather my procedure for discovering them.

My hasty and highly personal appraisals of books have no value to anyone but me. I however enjoy my 3" x 5" boondoggle. It costs only a few minutes a month and forces at least a brief pause for station identification before a completed book is returned to the shelf or otherwise disposed of. It requires no bulky equipment - travelers can use scraps of paper until they return to home base. It can be played day or night in any weather, by persons of any age. So, before 3" x 5" cards are entirely replaced by whispers to a computer, and my brand of solitaire becomes as obsolete technologically as grinding laundry through a wringer, let me commend the project to those who, like me, hate to put a good book away without a respectful bow to its author and realize that even a bad book appears in print only after an infinity of anguished effort on the part of its perpetrator.

Robert E. Asher is a member of the Senior Staff, Division of Foreign Policy Studies,Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C.He is the author or co-author of severalbooks and numerous articles on foreign policy questions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

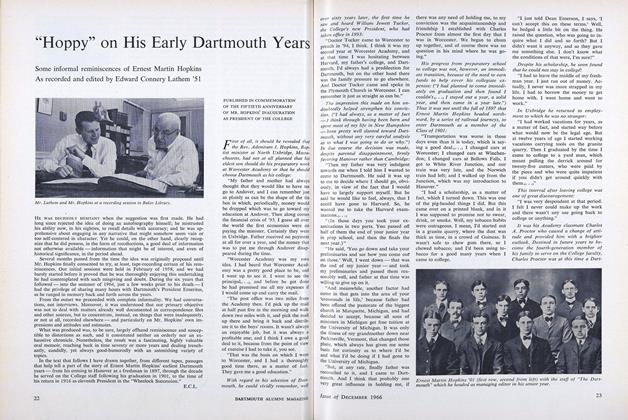

Feature"Hoppy" on His Early Dartmouth Years

December 1966 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Philosophy of Culture

December 1966 By ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32 -

Feature

FeatureContemporary Man

December 1966 -

Feature

FeatureToro's President

December 1966 -

Feature

FeatureHigh School Principal

December 1966 -

Feature

FeatureSpace Salesman

December 1966