By RichardEberhart '26. New York: The EakinsPress, 1967. Unpaged. $4.50.

Between 1930 and 1965 Richard Eberhart published 14 volumes of poetry. His 15th raises problems. He stopped at sonnet 31 because before he could write 69 more to make an even 100, his passion "ran out." Only one or two were published in little magazines. The rest were put away "as being too personal, too youthful, and too imitative." Every ten years or so, Eberhart would reread them, ponder the change of a word, a mark of punctuation, and the rephrasing of a line. About 20 years ago he seriously considered rewriting them, but he could not "make a start."

Why publish them now, unrevised? (1) Eberhart wishes "to see them in a small book by themselves." (2) To offer the reader "a concentration of work of an early, formative period." (3) To give a backward glance to readers interested in his later work.

Robert Frost tested poems by examining rhymes first. If a poet were consciously whimsical, odd rhymes could do good shock work. Tragically concerned with emotions, Eberhart gains little with his: spaniel and manual, necessity and immensity, spring and stings, sparkle and darkle, evening and receiving. So inexpert is the early Eberhart, or so defiant, that in Elizabethan quatrains he rhymes only odd numbered lines and on occasion leaves the final couplet unrhymed.

What emotions? Thwarted love. The woman is cruel. The "foppish" rival, also "well dressed," is compared to a scorpion, a wasp, a tiger, and "a fabled monster." The girl's wedding night requires the poet's exile. The nuptial couch is the bed whereon he died. Exalted, he will couple with her in the skies. He would like to lie with "honest worms," which "infect his suspect bones" and his "stallion's blood." But no, he will rely on heaven and shake his fists at fate. His "barbarous passions rot in their own excess." He may become "embalmed and mummified in his grotesque dream of love." Time diminishes his anger, and "poetry is lies! lies! lies!" "Poetry has slipped to muddy prose." He wishes to curse his pen "into the stinking sewer."

Four sonnets before the book ends, Eberhart happily has the strength to be faithless to his perverse mistress, now married. He will "salute the eternal feminine in Portia, Rosalind, Olivia, Julia, or Sylvia." His agony abating, he sings "praises full of love to the sensuous beauty of the beauteous world" and feels the gentle influence of the stars.

Should these poems have been published without revision? No, if you are doubtful about the final lines of one sonnet:

But what is the toll of words so inspissated At loss of reality they would outrealize?

Yes, if you accept Eberhart in his delight of speaking "savage delicious" in his "secretear."

Mr. Hurd was a member of the Departmentof English at Dartmouth from 1927 to 1964.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMore Dividends Than Expected

October 1967 By MARION BLYTH -

Feature

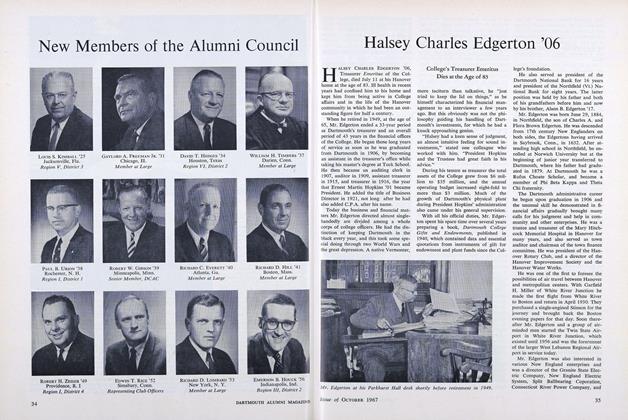

FeatureThird Century Fund Leaders ...

October 1967 -

Feature

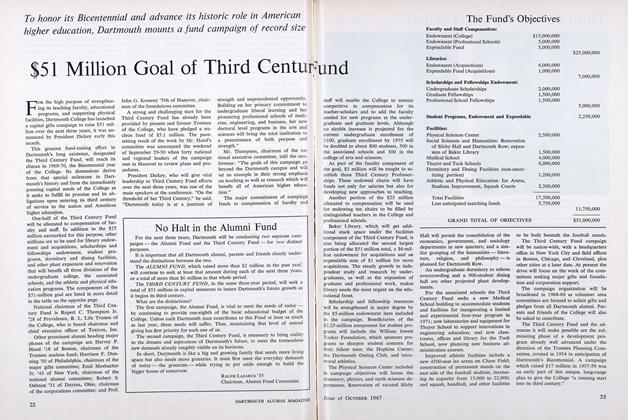

FeatureHalsey Charles Edgerton '06

October 1967 -

Feature

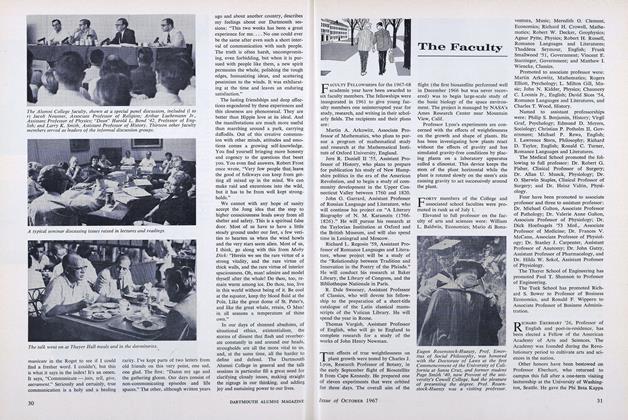

Feature$51 Million Goal of Third Century

October 1967 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

October 1967 -

Article

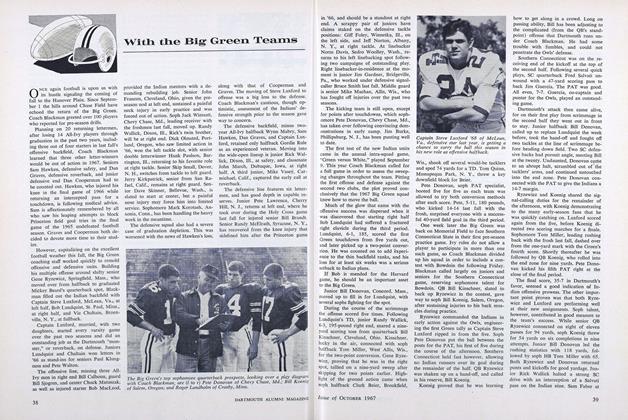

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1967

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

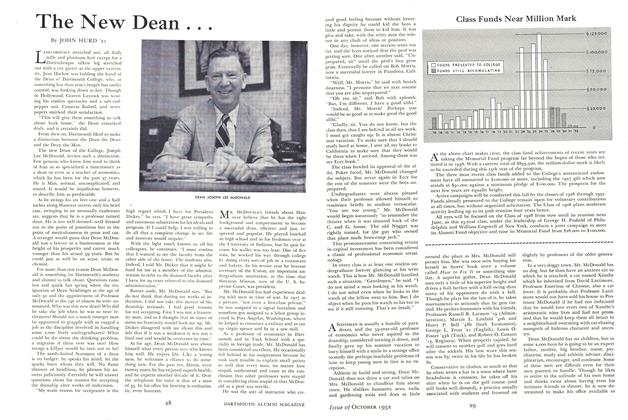

ArticleThe New Dean . . .

October 1952 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE MOST AMAZING BUT TRUE.

JUNE 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksSPAIN'S IRON AND STEEL INDUSTRY.

OCTOBER 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

JUNE 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

Books"SUNNY INTERVALS." A BOOKMAN'S MISCELLANEA: LONDON/SAN FRANCISCO/HANOVER.

FEBRUARY 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleEllwood Huff Fisher '21: A Tribute

September 1975 By JOHN HURD '21

Books

-

Books

BooksPRISONERS OF PSYCHIATRY: MENTAL PATIENTS, PSYCHIATRISTS, AND THE LAW.

MARCH 1973 By ARDEN BUCHOLZ '58 -

Books

BooksL'AMOUR EN BOUTON,

January 1951 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksTHE GOLDEN BOOK OF PRAYER

February 1942 By Rev. Chester B. Fisk -

Books

BooksTHE SIOUX, Life and Customs of a Warrior Society.

JULY 1964 By ROBERT A. McKENNAN '25 -

Books

BooksAN EVALUATION OF VISUAL FACTORS IN READING

December 1938 By Theodore F. Karwoski. -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN AGRICULTURAL PRESS

April 1941 By W. R. Waterman