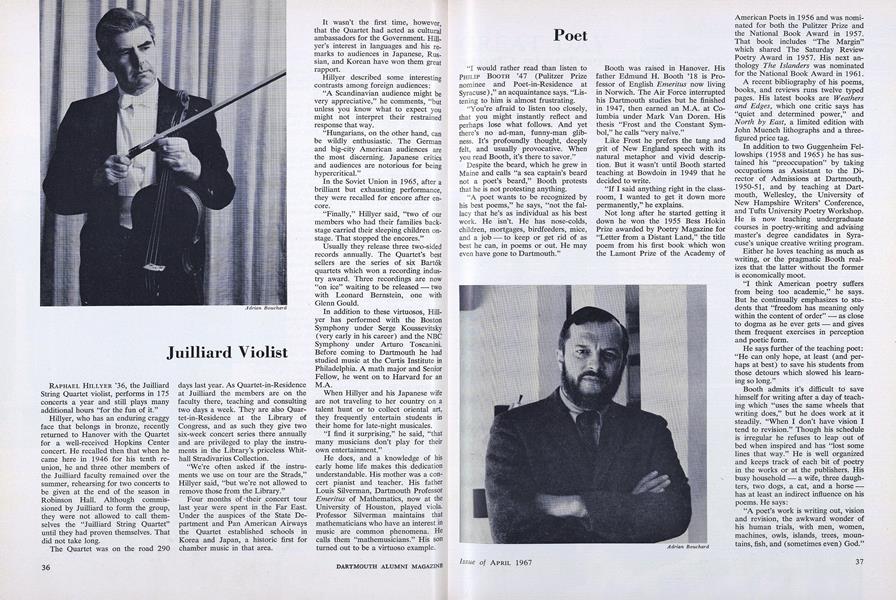

"I would rather read than listen to PHILIP BOOTH '47 (Pulitzer Prize nominee and Poet-in-Residence at Syracuse)," an acquaintance says. "Listening to him is almost frustrating.

"You're afraid to listen too closely, that you might instantly reflect and perhaps lose what follows. And yet there's no ad-man, funny-man glibness. It's profoundly thought, deeply felt, and usually provocative. When you read Booth, it's there to savor."

Despite the beard, which he grew in Maine and calls "a sea captain's beard not a poet's beard," Booth protests that he is not protesting anything.

"A poet wants to be recognized by his best poems," he says, "not the fallacy that he's as individual as his best work. He isn't. He has nose-colds, children, mortgages, birdfeeders, mice, and a job — to keep or get rid of as best he can, in poems or out. He may even have gone to Dartmouth."

Booth was raised in Hanover. His father Edmund H. Booth 'lB is Professor of English Emeritus now living in Norwich. The Air Force interrupted his Dartmouth studies but he finished in 1947, then earned an M.A. at Columbia under Mark Van Doren. His thesis "Frost and the Constant Symbol," he calls "very naive."

Like Frost he prefers the tang and grit of New England speech with its natural metaphor and vivid description. But it wasn't until Booth started teaching at Bowdoin in 1949 that he decided to write.

"If I said anything right in the classroom, I wanted to get it down more permanently," he explains.

Not long after he started getting it down he won the 1955 Bess Hokin Prize awarded by Poetry Magazine for "Letter from a Distant Land," the title poem from his first book which won the Lamont Prize of the Academy of American Poets in 1956 and was nominated for both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award in 1957. That book includes "The Margin" which shared The Saturday Review Poetry Award in 1957. His next anthology The Islanders was nominated for the National Book Award in 1961.

A recent bibliography of his poems, books, and reviews runs twelve typed pages. His latest books are Weathersand Edges, which one critic says has "quiet and determined power," and North by East, a limited edition with John Muench lithographs and a threefigured price tag.

In addition to two Guggenheim Fellowships (1958 and 1965) he has sustained his "preoccupation" by taking occupations as Assistant to the Director of Admissions at Dartmouth, 1950-51, and by teaching at Dartmouth, Wellesley, the University of New Hampshire Writers' Conference, and Tufts University Poetry Workshop. He is now teaching undergraduate courses in poetry-writing and advising master's degree candidates in Syracuse's unique creative writing program.

Either he loves teaching as much as writing, or the pragmatic Booth realizes that the latter without the former is economically moot.

"I think American poetry suffers from being too academic," he says. But he continually emphasizes to students that "freedom has meaning only within the content of order" - as close to dogma as he ever gets - and gives them frequent exercises in perception and poetic form.

He says further of the teaching poet: "He can only hope, at least (and perhaps at best) to save his students from those detours which slowed his learning so long."

Booth admits it's difficult to' save himself for writing after a day of teaching which "uses the same wheels that writing does," but he does work at it steadily. "When I don't have vision I tend to revision." Though his schedule is irregular he refuses to leap out of bed when inspired and has "lost some lines that way." He is well organized and keeps track of each bit of poetry in the works or at the publishers. His busy household a wife, three daughters, two dogs, a cat, and a horse has at least an indirect influence on his poems. He says:

"A poet's work is writing out, vision and revision, the awkward wonder of his human trials, with men, women, machines, owls, islands, trees, mountains, fish, and (sometimes even) God."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLife with Uncle

April 1967 -

Feature

FeatureDICK'S HOUSE

April 1967 -

Feature

FeatureUNCLE SAM AT DARTMOUTH

April 1967 By C. E. W. -

Article

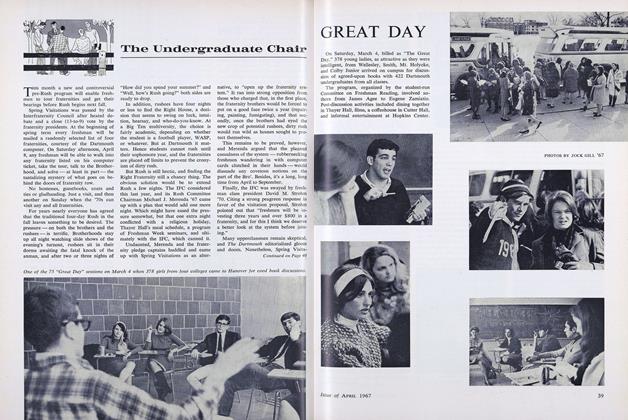

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleEloquence at Gettysburg and Daniel Webster

April 1967 By EARL W. WILEY '08 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

April 1967 By MACOMBER, JOHN s. MAYER